Following Feathers from Birds to Dinosaurs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

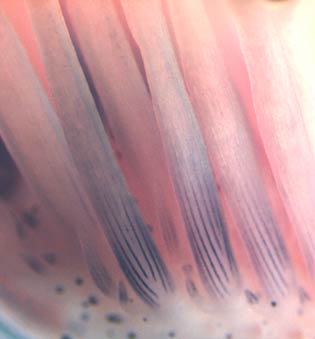

Richard Prum, a biologist at Yale University and the director of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, is one of the leading experts on the evolution of feathers and the relationship between birds and their dinosaur ancestors Recently, Prum and his colleagues showed that an ancient, 47-million-year-old bird had colored feathers, a first step that may eventually help scientists determine the color of feathers on some dinosaurs. Recently, Prum won a MacArthur Foundation grant to support his research. For more on Prum's work, see the university press release or Prum's website. For more on Prum, see his answers to the ScienceLives 10 Questions below.

Name: Richard O. Prum Age: 48 Institution: Yale University Field of Study: Evolutionary Ornithology

What inspired you to choose this field of study? I started bird watching at the age of 10 in a small town in Vermont. When I got to college, I discovered that evolutionary biology was the field of science that deals with the subject I found so interesting in birds – their diversity. I never really considered doing anything else, and luckily I haven't had to!

What is the best piece of advice you ever received? I have a better memory of the bad advice I received and ignored: "We worked this all out years ago!" "Why would you write about that? There's nothing to say." "Don't you think you should pick a project that isn't so ambitious?"

What was your first scientific experiment as a child? I have always been more of a natural historian than an experimentalist. But at about 12 or so, I took some international orange colored yarn that my mom used to knit hats and mittens for us to wear during hunting season. I put small pieces of orange yarn on bushes in the yard for birds to use in their nests. I hoped that the bright color would help me track the nests that used the yarn. Sure enough, a pair of Cedar Waxwings used a large amount of the orange yarn in their nest in a box elder tree. I collected the nest at the end of the season, and I think the nest may still be sitting in a box in my attic.

What is your favorite thing about being a scientist? The freedom to pursue creative work in a supportive environment. This includes thinking about new ideas, testing them, getting students and post-docs involved, challenging one another's ideas, travel and field work, and teaching classes for different levels of students. It all adds up to an enormously fulfilling and enriching way to live!

What is the most important characteristic a scientist must demonstrate in order to be an effective scientist? In addition to working energetically, thinking clearly, being honest, and behaving ethically, I think a critical component to successful science is becoming comfortable exploring the limits of your understanding. Many students and professional scientists are afraid of what that they don't understand, and tend to stick conservatively to areas they know well. Creative sciences require stretching yourself to your limits, and getting comfortable working with ideas that are unfamiliar and even scary.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What are the societal benefits of your research? Most of my research is really for its own sake – advancing our knowledge of the biology of birds and the history of life on this planet. However, this information may help in conservation biology. Some our research on self assembly of color-producing feather nanostructures may also lead to new manufacturing methods for photonic materials.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? When I was an undergraduate at Harvard in the early 1980s, there was an intellectual revolution in progress over how to reconstruct the history of life, and whether the classification of organisms should reflect this history. I was exposed to the debate in phylogenetics through a cohort of brilliant young graduate students who were far ahead of most faculty on this issue – including Michael Donoghue, David Maddison, Brent Mischler, Jonathan Coddington, and others. They inspired me to realize that ideas matter, that doing science was exciting, that new people were needed to pursue this important work, and that there were great opportunities ahead. It was a fantastic introduction to the world of science, and it gave me lots of reinforcement as a young researcher.

What about your field or being a scientist do you think would surprise people the most? Scientists are a lot more like artists than most people realize. We are driven by inspiration, and require constant contact with our creative "muse."

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? Decades of field notes, and bird sound and video recordings! They are totally irreplaceable.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car? Music is really important to me. I especially love all sorts of classical music – chamber music, opera, art songs. But I hate classical music stations that announce "We're going to play some music to help you relax and unwind..." I don't want to relax! I want to be intrigued, beguiled, and challenged! I want to feel something, not be put to sleep!

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus