Spikes on Genitals Help Flies Hook Up

When fruit flies hook up, they really hook up.

Scientists now find that spikes on the genitals of male fruit flies literally help them hold onto females.

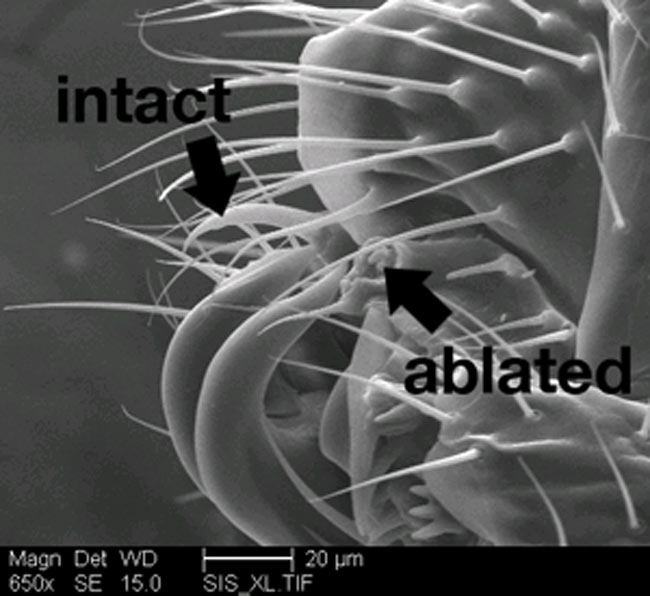

Using a laser, researchers zapped off tiny claw-like spines from the genitals of virgin male fruit flies (Drosophila bipectinata) from Cape Tribulation in Australia. Other scientists had suggested these hooks helped deliver sperm into wounds they might inflict, just as how bedbugs have sex.

The researchers found spineless males essentially slid off females, making them drastically less able to copulate and compete against rival males for mates. However, if the males were nevertheless able to have spineless sex, they apparently had normal insemination and fertilization rates.

These spikes latch onto the outside surfaces of female genitals during sex, not inside the female. The investigators suggested they acted much like grappling hooks or Velcro, perhaps behaving like seatbelts on a bucking bronco so that males could hold on.

"In Drosophila, unwilling females resist male sexual advances by vigorous kicking with their hind legs, bucking, extruding their genitalia in telescoping fashion, and if all else fails, by simply running or flying away from eager males," said researcher Michal Polak, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Cincinnati. "The spines may be an evolutionary solution in males to overcome these forms of female resistance."

Zapping genitals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Genitals in many animals, from insects and birds to primates, are exceedingly diverse in shape, evolving much faster relative to other body parts.

- Male beetles also have genital spines, and the females have evolved tougher genitals to help thwart damage.

- Mallard ducks have evolved ridiculously long phalluses and twisted vaginas.

- The clitoris of a hyena can protrude up to 7 inches from her body, forcing males to be very accurate in their positioning.

Understanding the reasons for this remarkable trend in the animal kingdom has been a major challenge for evolutionary biologists, a problem even touched on by Darwin in his work, "The Descent of Man," Polak explained.

One major obstacle plaguing researchers striving to uncover the evolutionary function of genital features has been the downright tiny size of their various components. The researchers used lasers because they could zap off the smallest of structures, down to less than 1 micron in size, with little or no collateral damage to neighboring features.

"We had trouble getting males to hold absolutely still under anesthesia during surgery, for if the male was too jittery, it was easy to miss our target, overshoot, and burn the male genitals in places that we, and presumable also the unfortunate male, did not desire," Polak recalled. "By trial and error, we discovered that very young males — 24 hours of age — lie quite still under light anesthesia, which we then used in our experiments to avoid the problem of trying to zap a quivering target."

Grappling hooks or Velcro

It remains uncertain whether these spikes act like grappling hooks on unwilling targets or like Velcro hooks on a matching surface.

The spines routinely embed at one place on female genitals during copulation, suggesting there might be a pocket there males use to anchor. "If this view is correct, it would argue in favor of the Velcro hypothesis," Polak said.

Polak and his colleagues are now planning more laser studies on genitals.

"We are using the laser for a variety of projects, including to surgically excise other genital traits and the tiny but elaborate male sex 'combs' used in courtship, and to study their adaptive function in sexual selection," Polak says.

Polak and his colleague Arash Rashed detailed their findings online January 6 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

- Animal Sex: No Stinking Rules

- Very Strange: The Spider Sex Chronicles

- Animal Sex News

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus