New Dinosaur Discovered in Antarctica

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A hefty, long-necked dinosaur that lumbered across the Antarctic before meeting its demise 190 million years ago has been identified and named, more than a decade after intrepid paleontologists sawed and chiseled the remains of the primitive plant-eater from its icy grave.

A team led by William Hammer of Augustana College had unearthed the dino fossils in the early 1990s. They found a partial foot, leg and ankle bones on Mt. Kirkpatrick near the Beardmore Glacier in Antarctica at an elevation of more than 13,000 feet (nearly 4,000 meters). It wasn't until recently, though, that researchers examined the fossils.

"The fossils were painstakingly removed from the ice and rock using jackhammers, rock saws and chisels under extremely difficult conditions over the course of two field seasons," said Nathan Smith, a graduate student at The Field Museum in Chicago, who along with a colleague describes the dinosaur in the Dec. 5 issue of the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Extreme dinos

The Antarctic dinosaur was about 20 to 25 feet long (six to about 8 meters) and weighed in at 4 to 6 tons. Smith and co-author Diego Pol, a paleontologist at the Museo Paleontologico Egidio Feruglio in Argentina, determined the remains belong to a new genus and species of dinosaur from the early Jurassic Period.

Dubbed Glacialisaurus hammeri, the beast was a type of sauropodomorph, a dino group that includes the largest animals ever to walk the earth. Their sister group is the theropods, which include Tyrannosaurus rex, Velociraptor and primitive birds. The sauropodomorphs were long-necked herbivores and included the "true sauropods" Diplodocus and Apatosaurus (sauropods are a subset of sauropodomorphs).

While researchers don't know how G. hammeri used its tail, some of its relatives are thought to have wielded their tails as weapons, cracking the tail at supersonic speeds to produce a ground-shaking boom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dinosaur sprawl

The new results suggest sauropodomorphs were widely distributed in the Early Jurassic—not only in China, South Africa, South America and North America, but also in Antarctica.

"This was probably due to the fact that major connections between the continents still existed at that time, and because climates were more equitable across latitudes than they are today," Smith said.

Back then, most of the landmasses in today's southern hemisphere (including Antarctica, South America, Africa and Australia) formed the supercontinent Gondwana. The landmass started to break up in the mid-Jurassic, about 167 million years ago.

The Glacialisaurus discovery, along with that of a possible sauropod at roughly the same location in Antarctica, lends additional support to a theory that the earliest sauropods coexisted with their more primitive sauropodomorph cousins for an extended period, the researchers conclude.

"They are important because they help to establish that primitive sauropodomorph dinosaurs were more broadly distributed than previously thought, and that they coexisted with their cousins, the true sauropods," Smith said.

Other animal remains that have been collected in the neighborhood of G. hammeri include a nearly complete skeleton of a theropod dinosaur called Cryolophosaurus ellioti; pelvic bones from a possible sauropod dinosaur; a pterosaur humerus bone; and the tooth of a large tritylodont (a type of extinct mammal relatives).

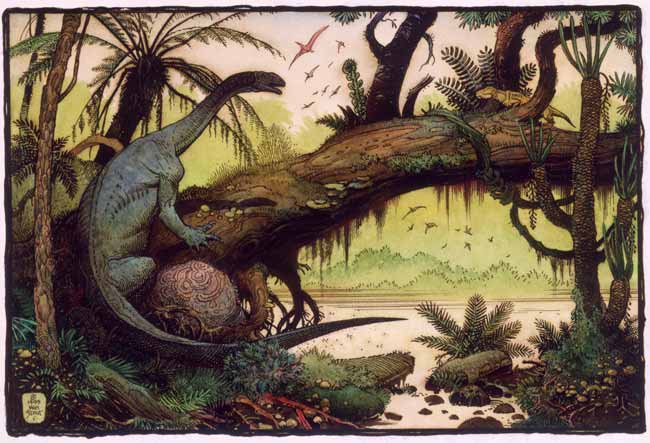

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Art

- Vote: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus