Asteroid Impact Would Devastate Seafloor Life, Too

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If an asteroid were to hit Earth and wipe out all life at the planet's surface, the creatures that live around deep sea hydrothermal vents would be safe from destruction, scientists have long thought. What goes on above the ocean's waves should be of little concern to creatures living 2 miles below.

But apparently it is, new research finds.

During a global catastrophe, the shrimp and mussels that thrive around these vents may be just as doomed as the rest of us.

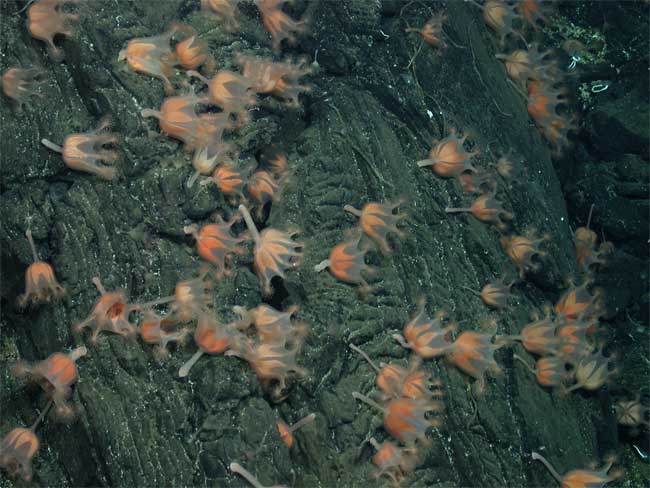

Creatures such as bacteria, shrimp and snails have flourished around hydrothermal vents, despite the fact that no sunlight reaches to the depths of the ocean floor. Instead, colonies get nutrition from the minerals dissolved in the superheated water that spews out from the vents.

Through a process called chemosynthesis, microbes convert the heat and minerals produced by the vents into energy. They then provide food to more complex forms of life, such as mollusks, crustaceans and worms.

Scientists had thought that because the food source of the creatures living around the vents was independent from the world above that an event such as a giant asteroid collision, which can kick up a cloud of debris that blocks the sun for months or years, wouldn't affect the vent ecosystems.

But new research done by Jon Copley of the University of Southampton indicates that the offspring of some of these creatures grow up away from the life-sustaining vents and depend for food on whatever material sinks down from the sunlit surface waters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, the vent inhabitants time the birth of their offspring with the seasons—even though they cannot see the sun. They time the release of their young to the spring bloom of the microscopic plant life that grows on the ocean's surface—stuff that sinks after it dies.

"I used to think these deep-sea communities would be safe from whatever havoc happens up here," Copley said. "But finding seasonality down there shows that life beneath the waves is far more connected than we realized."

Copley, who presented his research at the British Association for the Advancement of Science's Festival of Science, warns that because of this newly discovered susceptibility, deep sea vent communities could be impacted as climate change alters life in surface waters, though researchers have not found any evidence of climate change impacts in the deep ocean yet.

- Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- Images: Alien Life Deep Below Antarctic Waters

- Amazing Animal Abilities

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus