In Photos: Sea Life Thrives at Otherworldly Hydrothermal Vent System

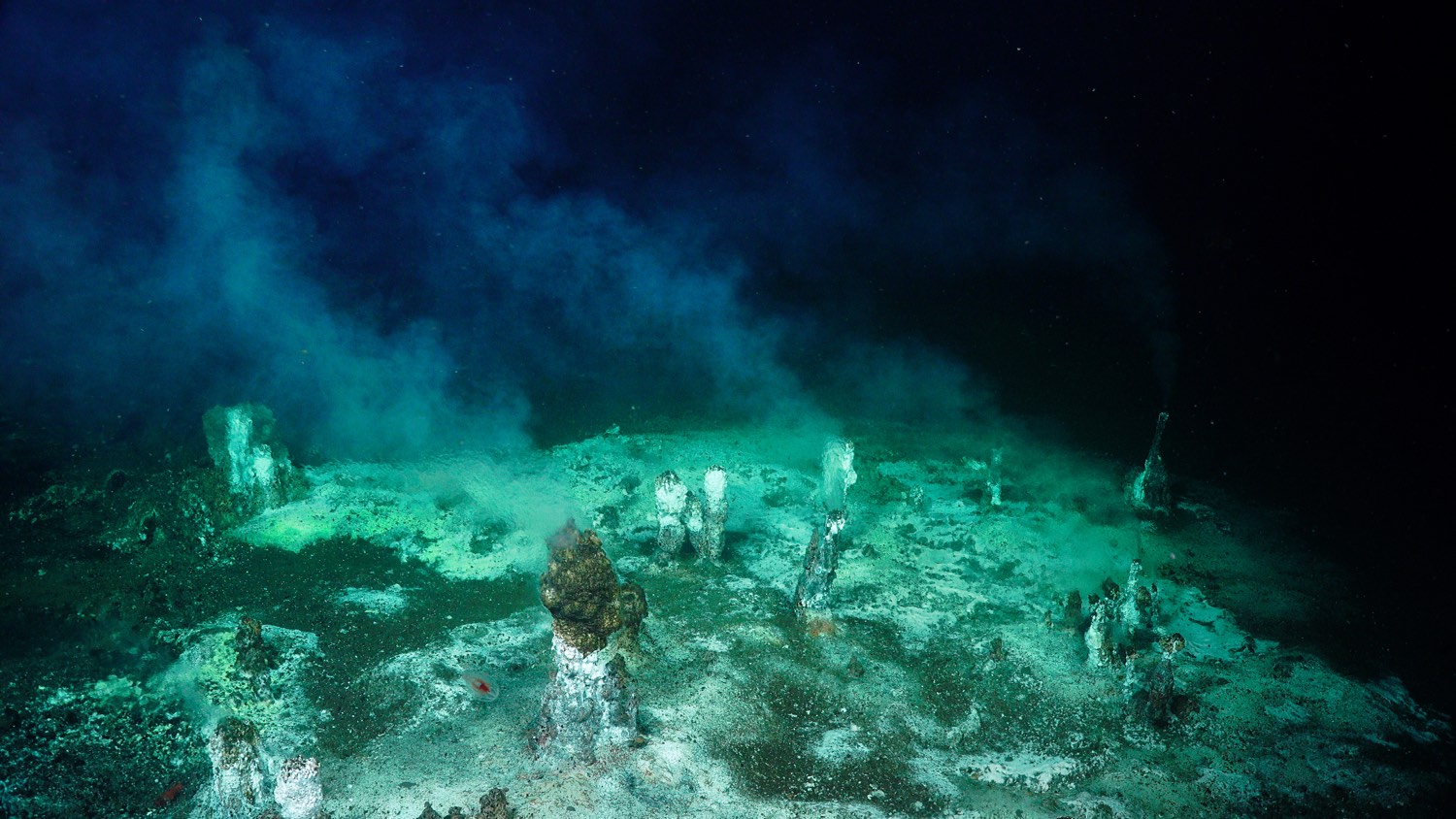

Psychedelic seascape

Hot hydrothermal fluids shimmer in otherworldly silver at an astounding new vent site discovered in the Gulf of California. Researchers explored this site for the first time in February 2019, maneuvering a remotely operated vehicle around mineral towers up to 74 feet (23 meters) tall. The methane- and sulfur-rich fluids feed a rainbow of bizarre life, like the Riftia tube worms seen nestled on this ledge. [Read more about the newfound hydrothermal vent system]

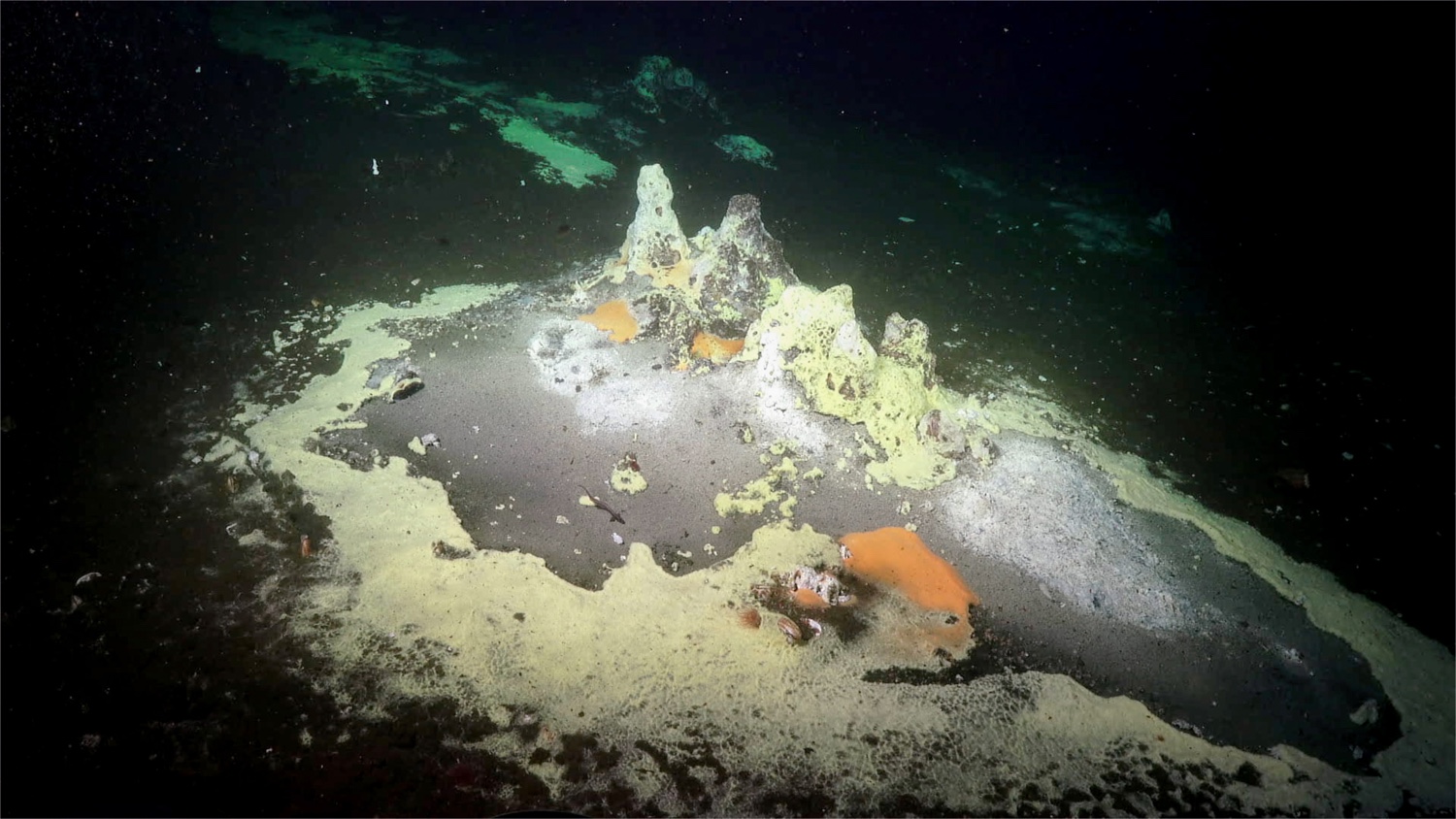

Microbial mats

Mats of yellow and orange microbes color the seafloor at the vent site, which is in the Guaymas Basin of the Gulf of California. Ten years ago, there was very little at this spot, but hydrothermal activity seems to have increased, feeding thriving communities of sea life. Microbial mats ranging in color from pink to purple to yellow and white thrive in the extreme environment of the vent field, where hydrothermal fluids heated to 690.8 degrees Fahrenheit (366 degrees Celsius) mix with seawater that is only 35.6 F (2 C).

Methane hydrates

Methane hydrates cling to a mineral ledge. Methane hydrates are bubbles of natural gas trapped in a crystalline lattice of ice. The methane hydrates at the Guaymas Basin site are strangely shaped, with an imperfect crystalline structure. Lead researcher Mandy Joye, a marine biologist at the University of Georgia, thinks that these strange shapes could be the result of high pressures, extreme temperatures or impurities in the natural gas.

Reflections

A scale worm, a type of marine worm often found at hydrothermal vents, rests on a mineral ledge under a pool of hydrothermal fluid. The boundary between the fluid and seawater refracts light, creating a silvery, mirror-like surface that creates a reflection of the spiny worm.

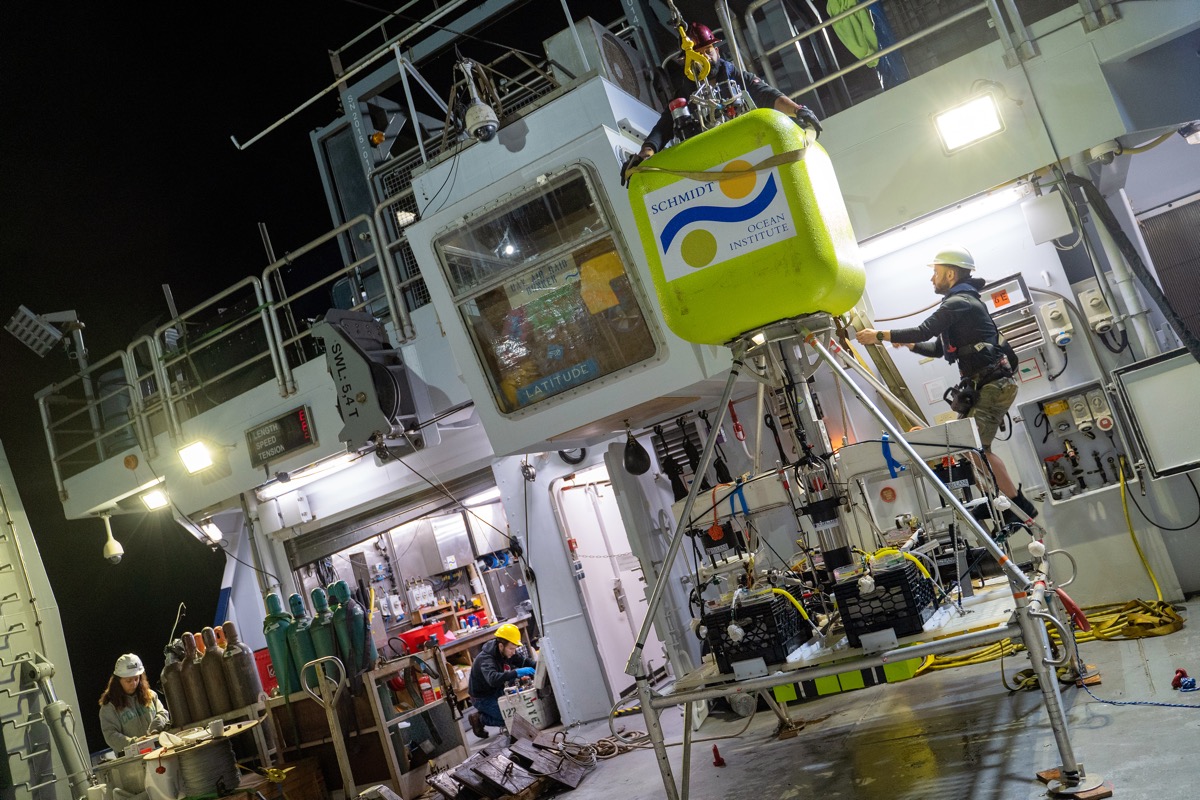

Control room

Researchers aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute vessel Falkor watch the feeds from their remotely operated vehicle in February 2019. The team was shocked at the complex mineral formations and variety of life at the vent site. "It was just a constant barrage of, 'You have got to be kidding me, that can't be real,'" Joye said.

Taking samples

Samples from the Guaymas Basin hydrothermal site are raised to the deck of the Falkor. Researchers are testing the water chemistry, microbiology and virology at the site. The hydrothermal fluids are rich in sulfur and methane, Joye said, and many of the identifiable organisms at the site are able to live off sulfur, or host symbiotic microbes that digest the sulfur for them. The mineral vents are also rich in iron and manganese.

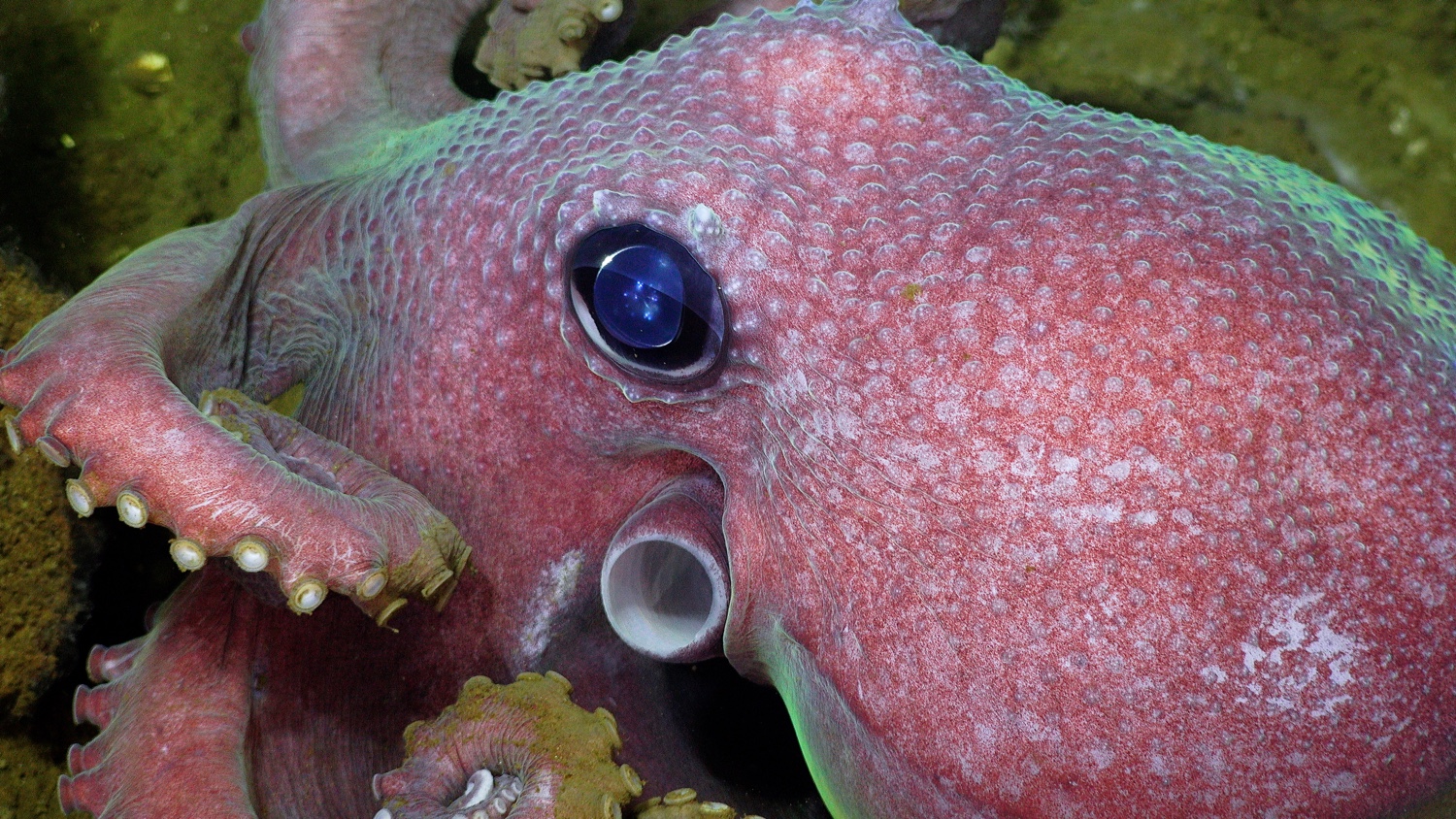

Friendly face

The research team's remotely operated vehicle gets up close and personal with an octopus at the Guaymas Basin hydrothermal site.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

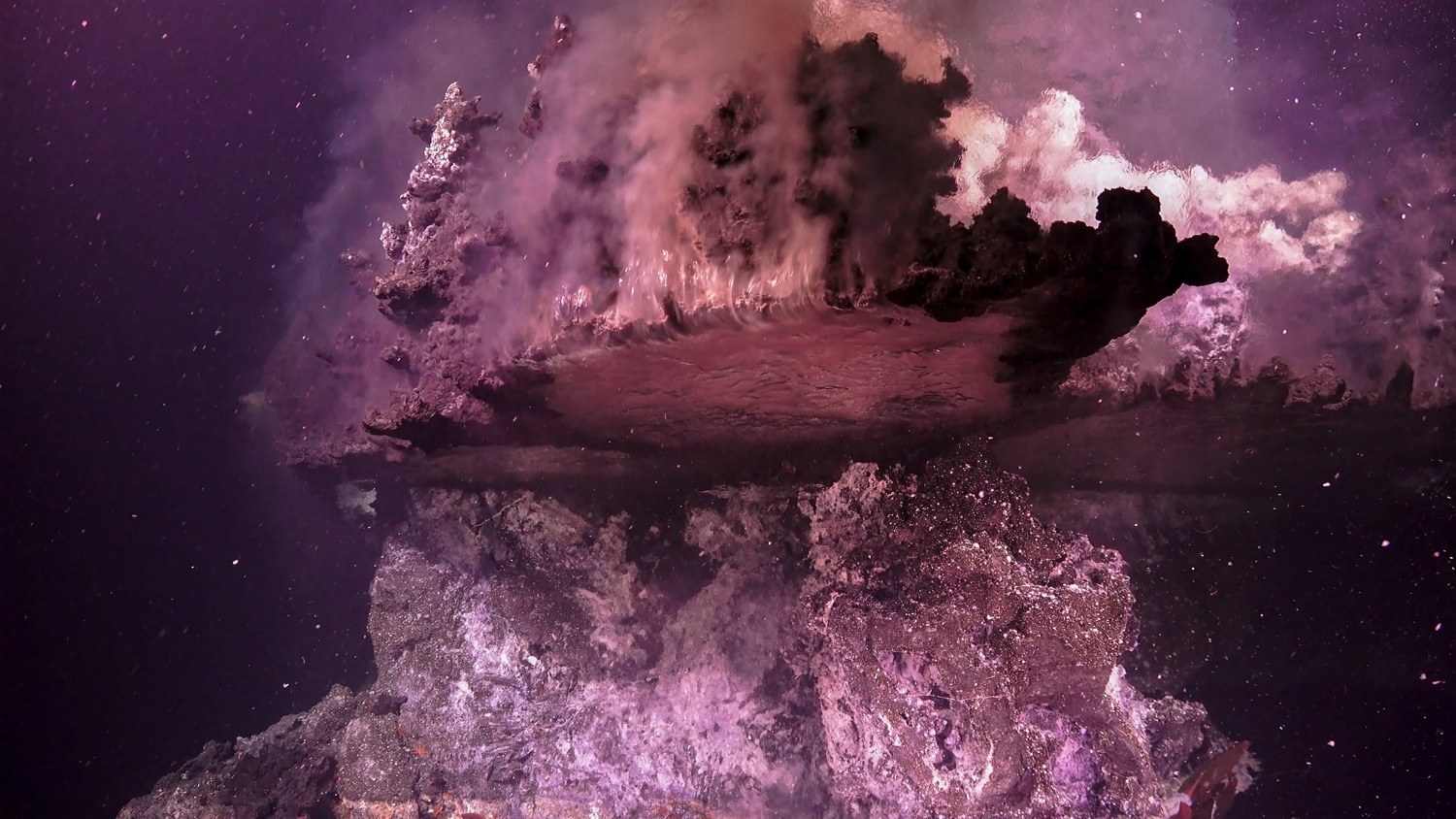

Amazing underworlds

Hydrothermal fluid bubbles upward, gets trapped by a mineral ledge, and spills up and over the edge in this shot taken by a remotely operated vehicle some 6,562 feet (2,000 m) below the surface of the Gulf of California. Chemical reactions between hydrothermal vents and seawater cause minerals to precipitate out and solidify, creating hulking mineral "pagodas."

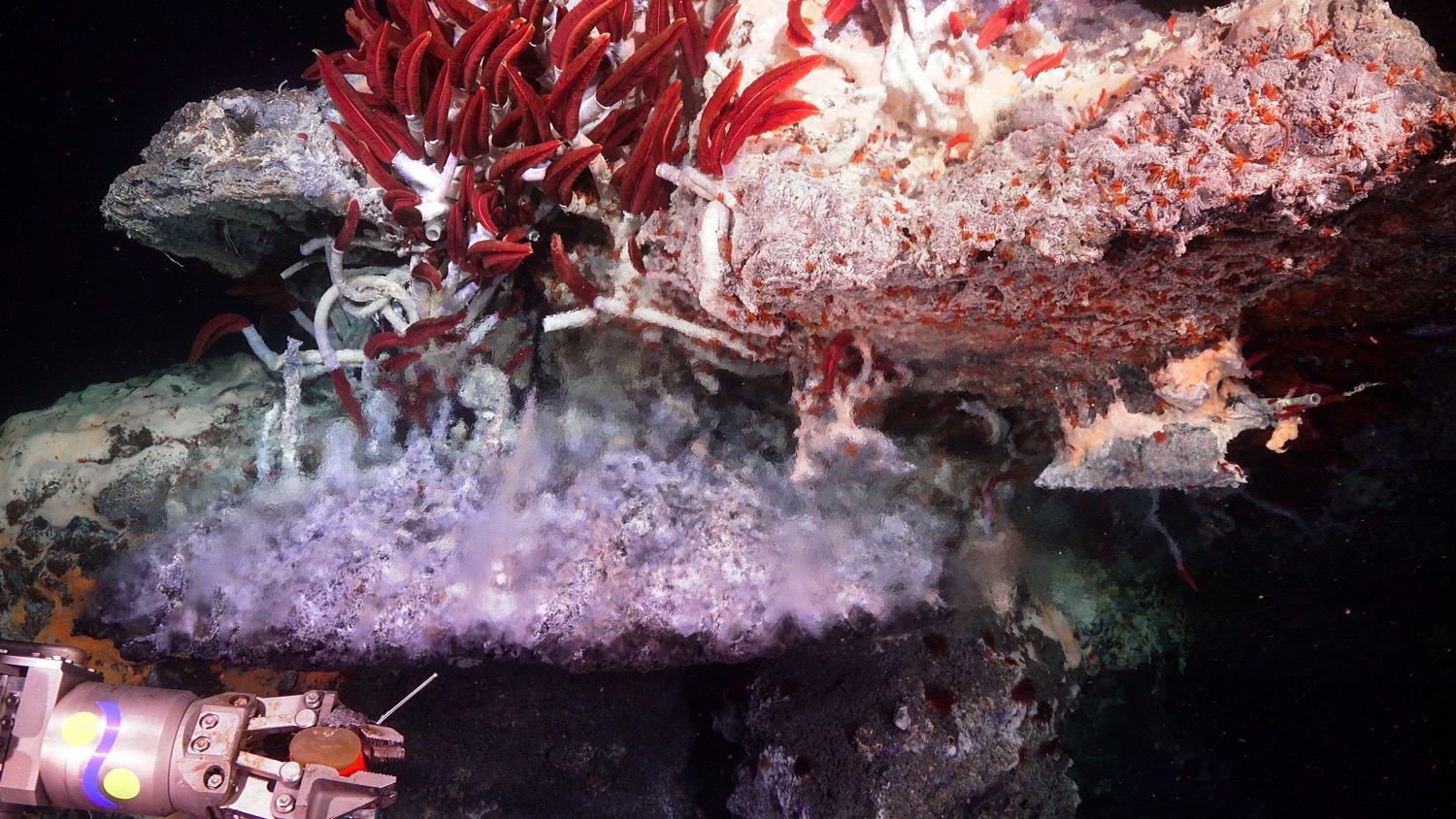

Tube worm paradise

The ROV SuBastian measures temperature near a hydrothermal vent as tube worms wave. Nothing like these hydrothermal vents has been found in the Guaymas Basin before, Joye said.

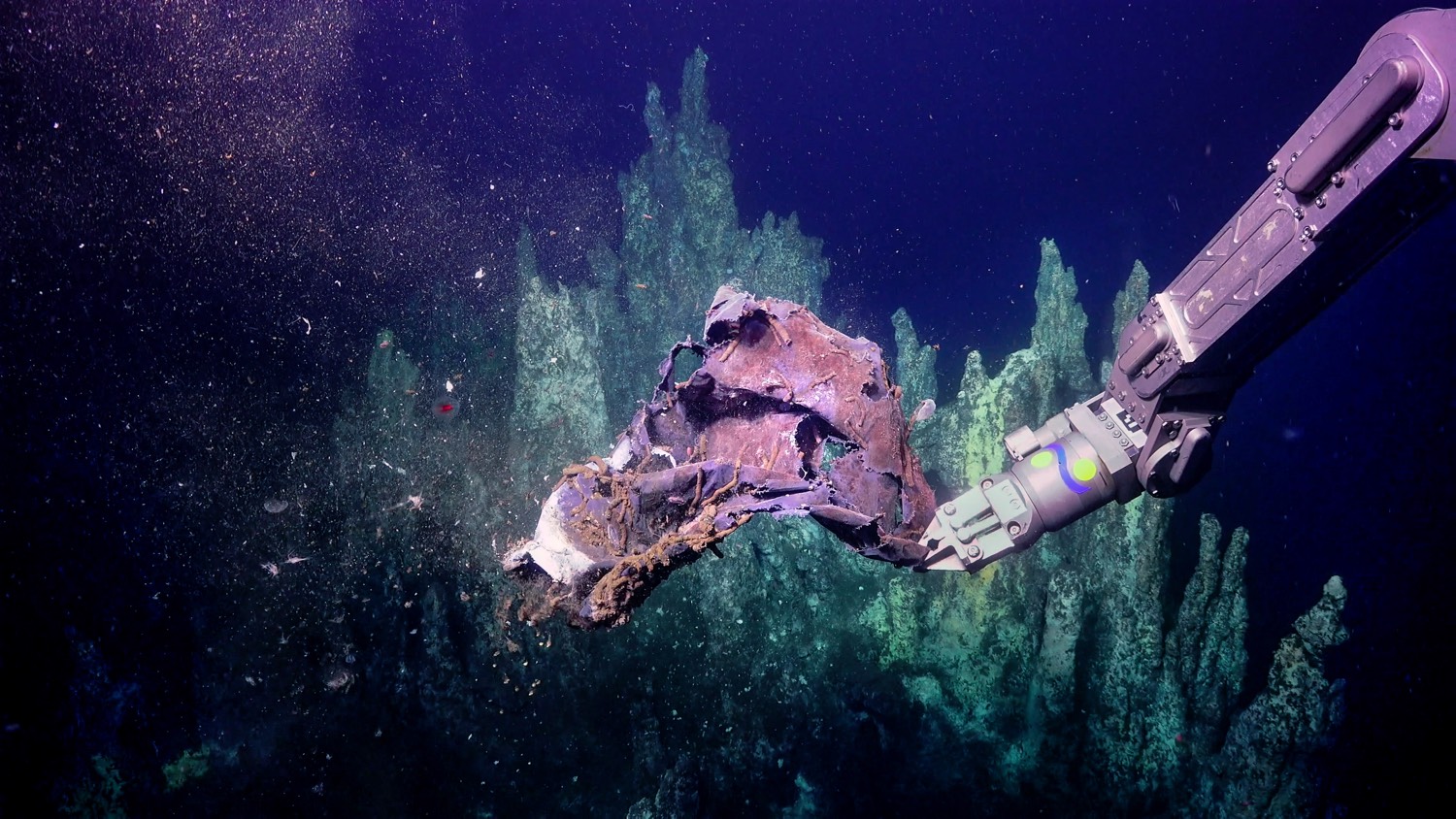

Ocean pollution

Even in this deep, remote area, humans have a footprint. In this image, the ROV SuBastian picks up a piece of garbage at the Guaymas Basin site. The team found other garbage, including discarded fishing nets and Mylar balloons, emphasizing the interconnectivity of the oceans.

Oil chimneys

Oil chimneys spew out hydrocarbon-rich fluids at the Guaymas Basin. Researchers are analyzing the hydrothermal fluids here. They're also sequencing genes from the microbes found at the site, as well as their viruses. All three might determine which microbes and other animals can thrive in this extreme environment.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.