Europeans Brought New, Deadly Ulcer Bacteria to Americas

Europeans who came to the Americas inadvertently introduced germs — including smallpox and measles — that killed upward of 90 percent of the native people. But now a new study finds that these now-infamous germs weren't the only ones the Europeans were carrying.

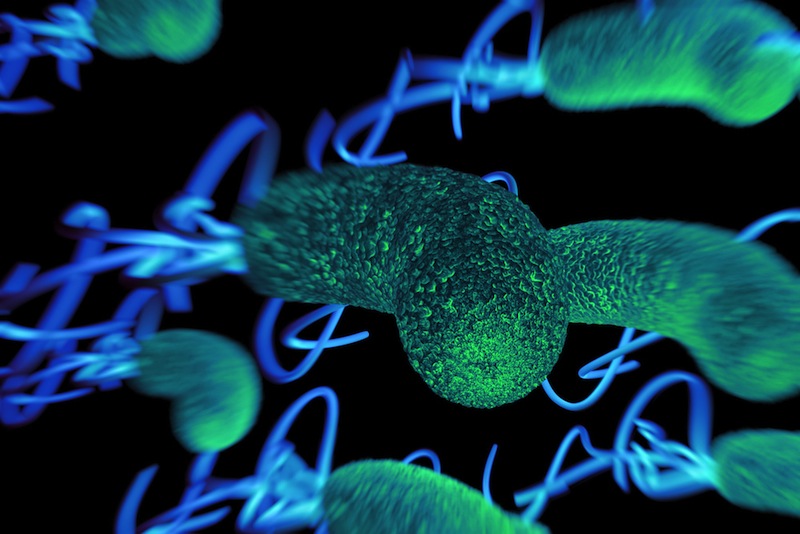

The Europeans (and their African slaves) also brought new strains of bacteria called Helicobacter pylori, known to cause gastric ulcers and stomach cancer, according to an international team of researchers.

The twist is that these "foreign" H. pylori strains didn't kill the local people quickly, like the smallpox virus did. Instead, the strains supplanted the local strain of H. pylori already present in the Americas, and eventually, led to a near extinction of the local strains. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The effects of this may be seen today. These Old World strains of H. pylori now infecting the multiethnic populations of the Americas may be one reason why South America, in particular, currently has some of the world's highest rates of ulcers and stomach cancer, the researchers said.

The provocative new study — a mix of anthropology, genetics and public health — appears today (Feb. 23) in the journal PLOS Genetics.

H. pylori is a bacterium found in the stomach, transmitted from person to person most commonly through exchange of saliva (oral-oral route) or poor hygiene in food preparation (oral-fecal route). More than half of the world's population is infected with the bacteria, although, globally, fewer than 20 percent of people will develop ulcers and fewer than 2 percent will develop stomach cancer as a result of the infection, according to the World Health Organization.

The rates of disease resulting fromH. pylori infection tend to be lower in the wealthier countries of North America, Europe and East Asia, but the rates remain high in South America and Central Asia. People can be treated with a regimen of antibiotics if they are diagnosed with a gastric ulcer caused by H. pylori.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, led by research fellows Kaisa Thorell of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and Koji Yahara of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Japan, scientists analyzed more than 400 H. pylori genome sequences from strains collected in North, Central and South America. They found that European and African strains were mixed together across the Americas, with little sign of the original American strains, suggesting that after the arrival of the newcomers, the foreign bacterial populations spread rapidly to people of different ethnicities, wiping out the local H. pylori strains.

"The pre-Columbian Americans had strains of East Asian ancestry [from their migration from Asia millennia ago], of which we nowadays only see traces of in remote communities," said Daniel Falush of the University of Bath in the U.K., the senior author on the study. "However, the reasons for the replacement will require more detailed investigation," he told Live Science. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About Your Microbiome]

But one reason why some populations living in the Americas today have high rates of ulcers and stomach cancer once infected may have to do with a "mismatch" between the ethnicity of the patient and the origin of the H. pylori strain they carry, Falush said. Studies have found a link between having such a mismatch and an increased risk of disease.

For example, in 2014, researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville reported that the African H. pylori strain was relatively benign in people of African ancestry yet far more disease-causing in people of mixed Amerindian ancestry. A similar study of this same group found that the European H. pylori strain was more likely to cause precancerous lesions in populations with native American ancestry than in European populations.

Falush said the new findings may be useful for future research on the connection between individual bacterial strains and their associated risk of causing gastric ulcers and stomach cancer in different human populations.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.