Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The birth of the world's first "three-parent baby," a child who carries genetic information from three different people, was recently announced.

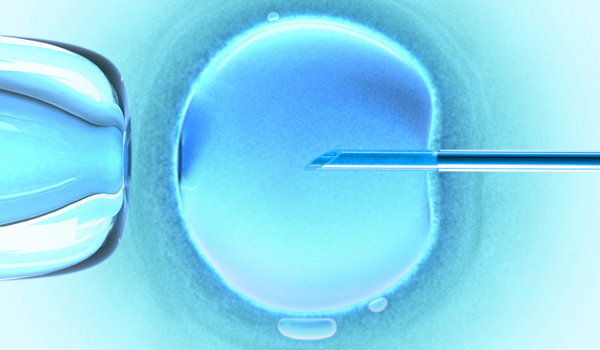

The baby was created via an IVF (in vitro fertilization) procedure that involved three people: the mother, the father and a woman who donated eggs. Scientists took DNA from the nucleus of the mother's egg cell and inserted that genetic material into an egg cell from the donor. The nucleus of the donor egg had been removed, but the egg still contained a bit of DNA from the donor woman: That is, it contained genetic material from the mitochondria, or the cell's energy powerhouses, which have their own DNA. The egg was then fertilized with sperm from the father.

In this case, the procedure was done because the eggs of the mother contained faulty mitochondria. This caused four miscarriages and the death of two of her children from a neurological condition called Leigh syndrome, the BBC reported.

This specialized IVF procedure is called spindle nuclear transfer. The Jordanian couple who underwent the method traveled from their home country to Mexico to have the procedure done.

"This work represents an important advancement in reproductive medicine. Mitochondrial disease has been an important and challenging problem. If subsequent research determines the safety and efficacy of spindle nuclear transfer, we look forward to it being an option for patients who risk transmitting mitochondrial diseases to their children," Dr. Owen Davis, president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, said in a statement.

Three-parent baby

In the spindle nuclear transfer in this case, the scientists took five egg cells from the mother and removed a cellular part called the spindle, which carries the mother's chromosomes. The researchers inserted these spindles into five donor eggs that had their nuclei removed, but which contained healthy mitochondria. The donor eggs then underwent in-vitro fertilization and developed for several days in a dish. Of the five early stage embryos, just one had a normal number of chromosomes. It was implanted into the mother, who gave birth to a healthy boy after 37 weeks of pregnancy.

A U.S. fertility doctor performed the procedure in Mexico, where there is little government oversight on such procedures. The technique is not currently approved in the United States.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ethicists and scientists are split on whether such altering of the DNA in an embryo is ethical. Some argue that the technique could help cure life-threatening conditions. Others say the procedure has not been tested long enough and argue that changing an embryo in this way could pave the way for "designer babies." That is, children could be selected for particular prized features such as blue eyes, blonde hair or high IQ.

In fact, scientists in Sweden recently began using a powerful genetic cut-and-paste tool known as CRISPR to edit healthy embryos. Those researchers did not let the embryos mature past an early stage of development, but similar techniques could, in theory, be used to design babies that have particular traits. [Controversial Human Embryo Editing: 5 Things to Know]

A separate debate surrounds the safety of fiddling with mitochondrial DNA. Proponents say the technique allows families to avoid passing on deadly conditions to their children.

For instance, Charles Mohan, CEO of the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation, previously told Live Science that such treatments let parents make decisions to foster the health of their children early on. Mohan lost his 15-year-old daughter to a mitochondrial disease, and did not know of his daughter's condition until she was 10 years old.

"It provides an alternative," Mohan said. "If we had known earlier, what decisions would we have made?"

But mitochondrial DNA is passed from a mother to her children, and her female children will then go on and pass that genetic material to their children. Therefore, creating these hybrid embryos involves deliberately altering the human lineage. Critics have said that the technique has not been sufficiently tested to ensure its safety and that the procedure could add new diseases to the human germ line.

"We know fiddling with mitochondrial DNA may make a massive difference to what happens to nuclear DNA," Lord Robert Winston, a professor of science and society and a fertility expert at Imperial College London, previously told Live Science. "Abnormal children have been born as result of mitochondrial transfer. … I think, in preventing one genetic disease, you are likely to cause another genetic disease."

Previously, the United Kingdom gave a green light to three-parent IVF to prevent mitochondrial diseases, which affect one in 6,500 people.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus