What the New Superbug Means for the US

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

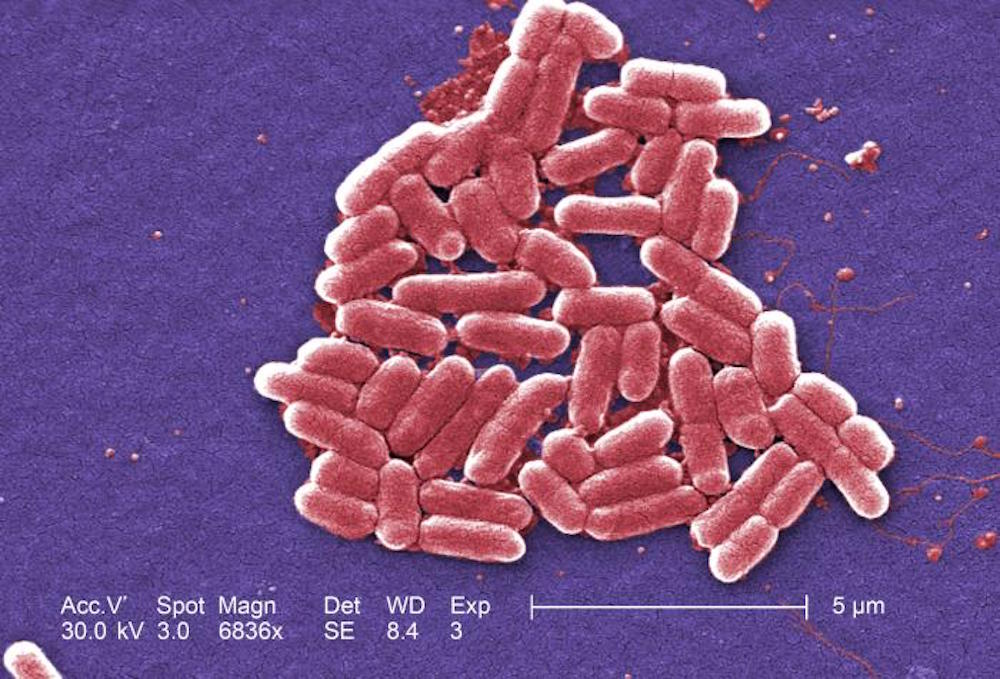

Experts say a Pennsylvania woman's recent case of an antibiotic-resistant infection shows the urgency for new antibiotics.

In the case, the E. coli bacteria causing the 49-year-old woman's urinary tract infection were found in lab testing to be resistant to an antibiotic called colistin. Doctors consider colistin a "last resort" drug — it can have serious side effects, such as kidney damage, so it is used only when other antibiotics do not work.

Currently, colistin is mainly used to treat people infected with a type of bacteria called CRE, or carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. E. coli is one type of enterobacteria, though not all E. coli strains have acquired resistance to carbapenem.

Bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics are the sort of thing that "[keeps] us awake at night," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious-disease specialist and professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine who was not involved in the woman's case.

Although doctors were able to treat the woman's infection with other antibiotics, the discovery of a colistin-resistant bug in the United States has experts on high alert. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

Indeed, ever since colistin-resistant E. coli were discovered in China in November 2015, labs in the U.S. have been on the lookout for similar strains, Schaffner told Live Science. Because of this extra attention, they were able to recognize it immediately in the woman's case, he said.

In addition to the United States, the superbug has been found in Europe, Schaffner said. That means there will be more cases of these bacteria, he said. It's unclear how widespread or how quickly the bug will spread, but Schaffner said he's "very sure that we'll see more instances of this."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This particular superbug will not only spread farther but could also give rise to completely new strains of superbugs, experts say.

That's because the genetic element that makes the bacteria resistant to colistin is found on a small, circular piece of DNA called a plasmid, Schaffner said. Plasmids are unique because they can be transferred easily from one species of bacteria to another, he said. Because of this, it's clear that this genetic element has the potential to spread to other strains of bacteria, although that hasn't happened yet, he said.

But if the plasmid that makes bacteria resistant to colistin were to spread to a CRE strain of bacteria (that was already resistant to carbapenem), doctors would not be able to use either powerful antibiotic to treat the infection.

The end of the line?

Doctors in Europe and the United States have encountered patients who have infections with bacteria that are resistant to a number of antibiotics and thus have almost no options for treatment, Schaffner said. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

In these cases, doctors may see if any experimental drugs are available or may try using combinations of antibiotics, Schaffner said. By combining drugs, it is sometimes possible to kill the bacteria, he said. Another option is to give a patient a higher-than-recommended dose of the antibiotic, he said.

There will always be mechanisms that allow bacteria to evade or become resistant to an antibiotic, Schaffner said. In other words, as researchers develop new drugs, bacteria will mutate to become resistant to them, and so on.

Therefore, there is a need to keep looking for and creating new antibiotics, Schaffner said.

The search is more difficult than it once was. The antibiotics that were the easiest to discover were found back in the 1940s and 1950s, Schaffner said. "These days, it will take more work" to find new drugs, he said.

But although more research on antibiotics is imperative, the detection of the superbug in the United States is not a cause for panic, experts say.

"I think, for the moment, those in [the fields of] public health and infectious disease will do the worrying for everyone," Schaffner said.

The most important thing that people can do is to not argue with a doctor if he or she tells you that you don't need antibiotics, Schaffner said. Don't insist on them, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus