Man's Fatal Rabies Mimicked Drug Side Effect

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

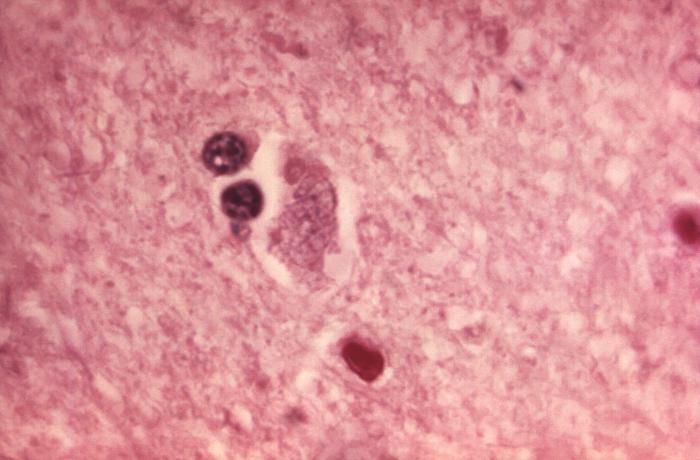

When a man in Missouri contracted rabies, his symptoms mimicked those of a serious drug reaction, making it hard for doctors to figure out the real cause of his illness until it was too late.

The case shows that "human rabies is a fatal disease, and we need to think out of the box" to diagnose the condition, said Dr. Bhavana Chinnakotla, a medical resident at the University of Missouri, who treated the patient.

The 52-year-old man went to the emergency room when he felt sudden and severe pain in his neck, and a tingling feeling in his left arm, according to a new report of his case. Doctors thought he had muscle and joint pain, and gave him a muscle relaxant called cyclobenzaprine.

But the next day, the man had a fever and was sweating and shaking all over, Chinnakotla said.

The man was diagnosed with serotonin syndrome, a reaction that people can have after taking certain drugs — including cyclobenzaprine — that causes the body to release too much of the brain chemical serotonin. The condition can cause heavy sweating, increased body temperature and loss of coordination. The man's symptoms "fit to that picture," Chinnakotla said.

During his first few days in the hospital, the man refused to drink liquids or have a small oxygen tube placed in his nose. The doctors didn't realize it at the time, but these are symptoms of hydrophobia (fear of water) and aerophobia (fear of air) that are sometimes seen in rabies patients, according to the case report.

The man didn't get better with the treatment for serotonin syndrome, and so the doctors tested him for a slew of infectious diseases, including herpes virus, West Nile virus, syphilis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All of these tests came back negative.

After speaking with the man's family, doctors learned that he lived in a trailer near the woods, and liked to photograph wild animals. Doctors then suspected rabies as a possible cause of the illness, which a test later confirmed.

Doctors should consider that serotonin syndrome and other conditions that cause elevated body temperature, known as hyperthermia syndromes, "might be masquerading manifestations of rabies," Chinnakotla said. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

Unfortunately, once a person starts to show symptoms of rabies, the disease is almost always fatal, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The man's condition grew progressively worse — he went into shock and his kidneys stopped working. He was unresponsive, and tests showed that the man didn't exhibit even the most primitive reflexes, which are carried out by the brain stem. After nearly two weeks in the hospital, the family decided to discontinue life support, and the man died within 40 minutes of being taken off a ventilator.

Rabies is rare in the United States — the man's case was just the second reported in Missouri in the last 50 years, the researchers said. The condition is caused by a virus that can be transmitted by the bite of an infected animal, including a bat. This may have been the case with the Missouri man — tests showed that he was infected with a strain of rabies linked with the tri-colored bat, the smallest bat species in North America.

People who are bitten by any animal should get a medical evaluation, according to the CDC. There is a "post-exposure" vaccine that can prevent rabies from developing in people who have been exposed to the virus, and anyone with a bite or scratch from a bat should get the vaccine, the CDC says.

But people who get rabies from a bat often don't realize they have been bitten, the researchers said. Bites from the tri-colored bat can be unnoticeable, Chinnakotla said.

The study was presented this month at IDWeek2015, a meeting of organizations focused on infectious diseases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus