540,000-Year-Old Shell Carvings May Be Human Ancestor's Oldest Art

The ancient, big-bodied relatives of modern-day humans not only ate freshwater shellfish, but engraved their shells and used them as tools, a new study finds.

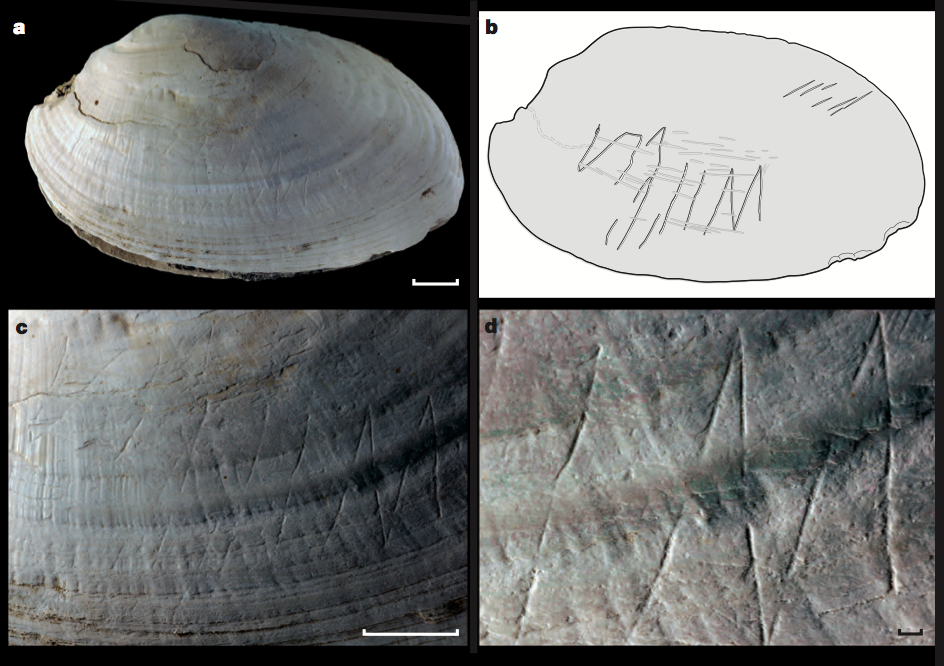

Researchers in Java, Indonesia, discovered engravings on a shell that dates to between 540,000 and 430,000 years ago. The ancient artwork could be the oldest known geometric carving made by a human ancestor, the researchers said.

It's unclear what the engraving — a series of slashes and an "M"-shaped zigzag — means, but it could indicate that Homo erectus, the ancestor of modern humans, may have been smarter than was previously thought. [See photos of the ancient mollusk shells from Indonesia]

"We as humans tend to be a bit species-centric — we think we are so great and they must have been a bit more stupid than us, but I'm not sure," said the study's lead researcher, Josephine Joordens, a postdoctorial researcher of archaeology at Leiden University, in the Netherlands. "We need to appreciate the capacities of our ancestors a bit more."

Shell study

The researchers studied 166 shells that were excavated in Java in the 1890s but are now stored at the Naturalis museum in the Netherlands. One of the shells has a smooth and polished edge, suggesting it may have been used as a tool for cutting or scraping. Another shell, the one with the engraving, was likely carved with a sharp object, such as a shark tooth, the researchers said.

At the time of its carving, the shell likely had a dark covering, and the marks would have appeared as white lines, Joordens said. Her team tried to engrave present-day freshwater shells and found the task difficult.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You had to use a lot of strength in your hands," Joordens said. "You had to be precise to make those angles. [But] if you engrave that dark surface and the white appears, that must have been quite striking for Homo erectus."

Homo erectus is known to have used stone tools, but this is the first evidence that they also used shells as tools, Joordens said. In Java, researchers have found less evidence of stone tool use, and the new shell finding may explain why.

"Given that they don't seem to be using stone tools as much, it's very interesting to discover evidence suggesting strongly that they were using tools made out of another kind of material," said Pat Shipman, a retired adjunct professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved with the study. "That broadens what we know of their behavioral repertoire." [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Seashells by the shore

In the late 19th century, the Dutch doctor Eugène Dubois became fascinated with Darwin's idea of evolution. Dubois wanted to find a transitional species between apes and humans, and decided to travel with the army to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) to look for clues.

His persistence paid off. In 1891, he found "Java Man," now known as Homo erectus(literally, "upright man"), a species that lived between 1.9 million and 100,000 years ago. Dubois excavated everything he could, including the fragile shells used in the new study.

"Dubois and this material have been extremely important in the history of anthropology," Shipman said. "It shows that, yes, you can go back to an old collection."

About one-third of the shells have a small hole that does not appear to be made by an animal, such as an otter, rat, bird, monkey or snail. About 80 percent of the holes are made in the same location — near the shells' hinges, and measure about 0.2 to 0.4 inches (0.5 to 1 centimeter) across.

It's a clever way to get a snack, "without smashing the shell, so that you have all kinds of debris and breakage in the meat of the animal," Joordens said.Perhaps Homo erectus pierced the shells with sharp points, such as the shark teeth that were found at Trinil, the archaeological site in Java, Joordens said. A modern-day experiment using a shark's tooth on a mollusk showed that once the shell is pierced, the animal looses control of its muscle and the shell can easily be pried apart.

It's possible Homo erectus ate shellfish and used the remaining shells for making tools, she said.

"We found at least one that was very clearly [and] deliberately modified so that a sharp edge was produced that could be used like a knife," Joordens said. "There are other shells in the collection that also have this tool-like appearance."

But the engraving on the shell is the "most spectacular part," she said. "It makes you wonder why it was made and what the purpose was, or what the person who made it wanted. And that's a very difficult question."

Instead of guessing at its meaning, the researchers simply present the finding, "because we cannot say what went on inside the head of Homo erectus at that time," Joordens said.

Skeletal remains

Dubois also uncovered a few fossilized bones at the Trinil site, including a femur that looked more modern than that of Homo erectus. But, the femur may look different because the individual had a handicap or disease, Joordens said.

A skullcap, which has a brain size too small to belong to a modern human, also came from the same layer as the femur, the researchers said.

The study will probably spur more research into the food, tools and culture of Homo erectus in Indonesia, said Frank Huffman, a research fellow of anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved in the study.

"What subsistence and cultural practices Homo erectus had in Java has been a mystery for 120 years," Huffman said. "[This study] has given us some the most intriguing behavioral evidence yet."

The findings were published online today (Dec. 3) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.