Another Dust Bowl? California Drought Resembles Worst in Millennium

The catastrophic 1934 drought is one of the worst North America droughts on record, and was caused, in part, by an atmospheric condition that may have led to the current drought in California, a new study finds.

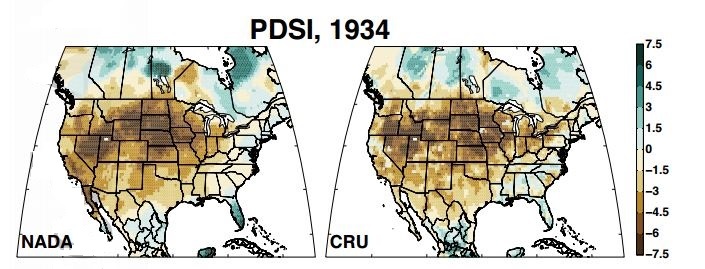

The 1934 drought affected about seven times more land area than other large droughts that hit North America between the years 1000 and 2005, and was almost 30 percent worse than the 1580 drought, the second most severe drought to hit the continent in the past 1,005 years.

"We noticed that 1934 really stuck out as not only the worst drought, but far outside the normal range of what we see in the record," lead researcher Ben Cook said in a statement. Cook is a climate scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City and holds a joint appointment at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. [Dry and Dying: See Stark Images of Drought]

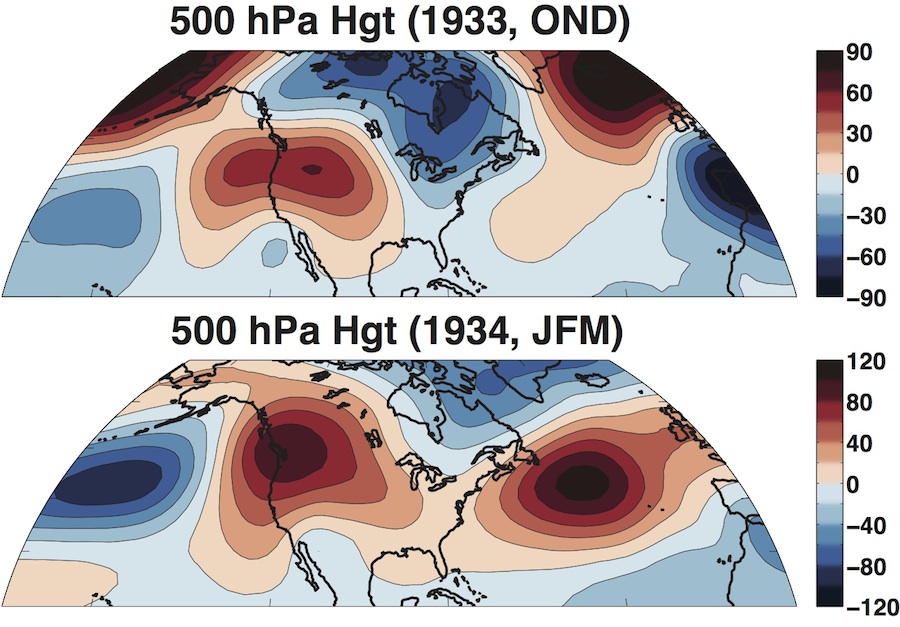

The same atmospheric phenomenon that emerged during the winter of 1933 to 1934 is also present today. This high-pressure ridge over the West Coast deflects storms holding much-needed rain, and may be causing the current drought crippling California, the researchers said.

"When you have a high-pressure system there, it steers storms much farther north than they would normally be," Cook told Live Science. "With this high pressure sitting there in the winter of 1933 to 1934, it blocked a lot of the rainfall and storms that you would expect to come into California."

It's unclear what causes the atmospheric ridge, however. "There's some evidence that maybe it could be forced by changes in ocean temperatures in parts of the Pacific, but by all accounts, it appears to be just a natural mode of variability in the atmosphere," Cook said.

This ridging pattern has been in place during some of the worst droughts to hit the West Coast, including the 1976 California drought, one of the worst dry spells in the state's history. California's current three-year drought is projected to cost the state $2.2 billion in 2014, and is predicted to continue in 2015, according to a July report from the University of California, Davis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the current drought is just a small fry compared with the one in 1934, which marked the start of a severe dry spell that spanned a decade, and eventually earned the name the Dust Bowl.

"What made 1934 really exceptional was, one, how intense it was, but also how widespread it was," Cook told Live Science. "Normally when we have droughts in the West, like we have now, they're very regional. [In 1934], you had extreme drought pretty much covering three-quarters of the western United States."

Farmers living in the plains at the time had decided to tear up native grasses and instead plant crops that were not drought resistant or tolerant to the dry conditions. Without water, these crops failed, leaving bare dusty fields that contributed to the massive "black blizzard" dust clouds.

Drought data

In the new study, the researchers analyzed data from the North American Drought Atlas, a database of drought reconstructions based on tree-ring studies that goes back 2,000 years. The scientists also analyzed records of air and sea-surface temperatures and precipitation. [The 5 Worst Droughts in US History]

Climate data and dust simulations also show how the dust storms intensified the 1934 drought and spread it throughout the western United States. Together, changes in sea-surface temperatures and lack of rainfall in the Northwest, Southwest and Southern Plains led to dry conditions in the fall of 1933. By the spring of 1934, the Central Plains and Midwest were considered to be in a severedrought.

Major dust storms in 1934 — the largest in North America since the Middle Ages — spread dust from the Central Plains toward the Atlantic Ocean, the study found.

Regions downwind from the dust storms suffered the most, including the Midwest states of Nebraska and Kansas. Dust particles that accumulated in the atmosphere above these states reflected the sun's energy back into space, disturbing normal air circulation patterns, blocking cloud formation and rainfall, and leading to dry conditions, the researchers said.

Nowadays, the U.S. government's Natural Resources Conservation Service works to limit wind and dust storm erosion that can lead to more dust being lifted into the atmosphere. Experts, such as soil biologists and geologists, help farmers and ranchers create conservation plans that help wildlife and ensure healthy and productive soils. "They can reduce the chance of a 1934 event occurring again," Cook said.

The study could help scientists understand what factors lead to droughts, and improve researchers' accuracy in predicting future dry spells, said Siegfried Schubert, a meteorologist at NASA's Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, who was not involved in the study.

"It is such an important problem for society to be able to predict these major droughts," he said.

The study was published online Sept. 23 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.