1976 Ebola Outbreak's Lesson: Behaviors Must Change

Scientists involved in fighting the first outbreak of Ebola in 1976 are pointing to a crucial difference between that outbreak and the current one in West Africa: the behavior changes among the affected communities.

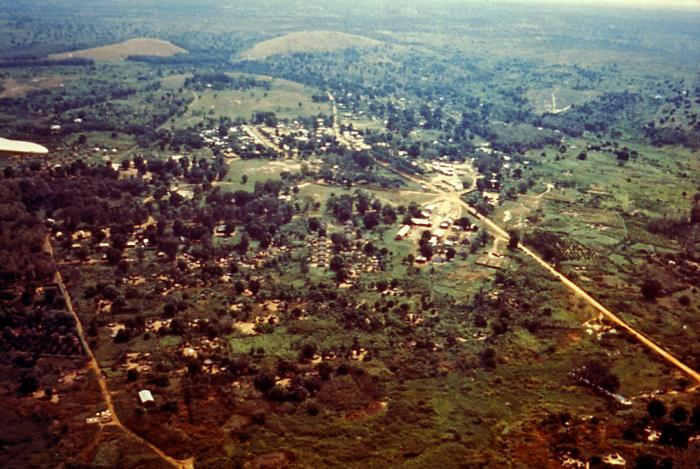

In a new study published today (Oct. 6), researchers revisited data from the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976 (then known as Zaire) to investigate why that outbreak was quickly contained, whereas the current outbreak rapidly spiraled out of control.

The 1976 outbreak was confined to one village and affected 318 people, resulting in 280 deaths. Since the current outbreak began in early 2014, more than 7,400 people have been infected and about 3,400 people have died of Ebola, according to the World Health Organization.

In 1976, the outbreak was traced back to contaminated needles at a hospital, where only five syringes were used each day to treat all the patients. The closure of the hospital helped; however, the researchers found evidence that the rate of new cases decreased considerably even before that hospital closed. [Ebola Virus: 5 Things You Should Know]

The decline of the outbreak most likely resulted from changes in the community's behaviors, such as altering traditional burial practices so that people could avoid catching the virus from dead patients, the researchers said.

"Ebola is not something you can just contain with hospital-based measures alone," Dr. Peter Piot, director and professor of global health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), said in a statement. Piot had traveled to what was then called Zaire to investigate the first outbreak of Ebola, an entirely unknown virus at the time.

"Getting the message out into the community and getting people to change their behavior is critical if we are to bring the current outbreak under control. Measures such as isolating patients, contact tracing and follow-up surveillance, and community education are all part of the response," Piot said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new report, the researchers used data on the original 1976 patients, along with Piot’s handwritten notes, to examine how the virus transmission unfolded during that first outbreak. Using a mathematical model, the researchers showed the rate of transmission at the start of that outbreak was high enough for it to have become an epidemic as large as the current outbreak in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the researchers said.

But it didn't, and that's because people changed their behavior to reduce the transmission of the virus.

"Crucially, we can see that this behavior change happened quickly — within a few weeks," co-author Anton Camacho, also of the LSHTM.

Such a change in people's behaviors has not been seen in the current outbreak, the researchers said.

"As well as a huge international response, in-country efforts are needed to address the fear and mistrust of health workers and governments," Piot said. "We are a long way off catching up with the current outbreak, and even further from being in control of it."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.