Surgery in a Time Before Anesthesia (Op-Ed)

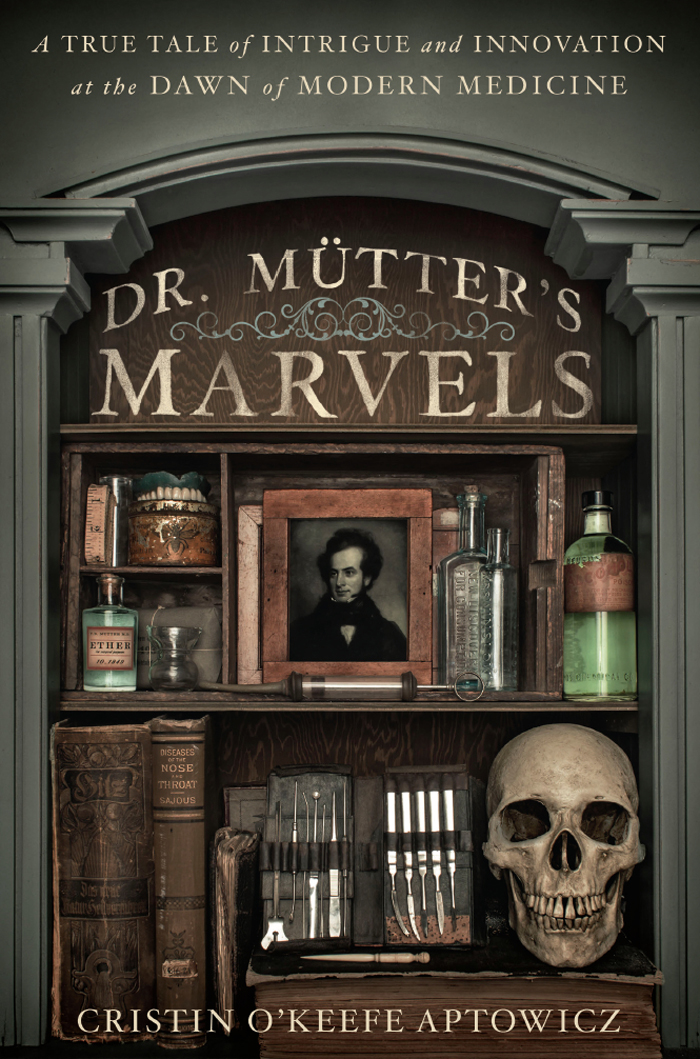

Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz, author of the new novel "Dr. Mutter's Marvels," released today. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

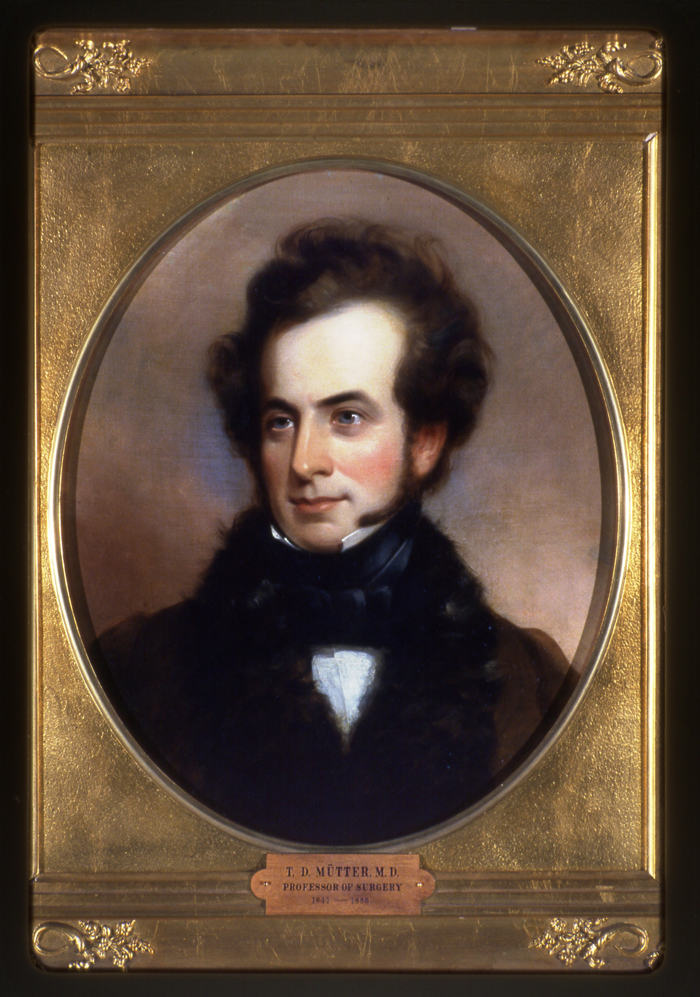

Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter was a pre-Civil War plastic surgeon who performed radical surgery on the severely deformed in a time before anesthesia. During his life and career, the American medical community saw enormous leaps forward when it came to innovations and discoveries — but in writing a nonfiction book about Mütter's work, I was amazed at how his story, and the parallel story of the development of anesthetics, illustrates the sometimes chaotic and furious path of scientific discovery. ['Dr. Mütter's Marvels' (US 2014): Book Excerpt ]

I had always assumed that medical science — so rooted in provable facts — would embody that clean upward line of success. But science, like life, is far more complicated.

An age before anesthetic

It is hard to imagine, as a person living in the twenty-first century, agreeing to surgery without hope of anesthesia. And yet, prior to the discovery of ether anesthesia in 1846, all surgeries — from minor to major or absolutely radical — were performed on people who were wide-awake, oftentimes held down on the operating table by men whose only job was to ignore the patients pleas, screams and sobs so that the surgeon could do his job.

Dr. Mütter lived and worked in this world, and spent the first half of his career developing and implementing strategies that he hoped would "alleviate human suffering" when it came to surgery — not only in the operating room, but before and after surgery, as well.

He would spend days massaging the faces or limbs of patients on whom he was slated to operate, to desensitize them to the touch of his hands and instruments, and improved his ambidextrousness so that he could perform his surgeries twice as quickly. [The Macabre Dr. Mutter's Freaky Medical Marvel]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the news of the first successful ether-aided anesthesia surgery exploded across the American medical world, Mütter was the first to embrace the new drug, performing Philadelphia's first ether anesthesia surgery just one month after the first one ever was performed in Boston. Within weeks of Mütter's successful ether surgery, the drug was banned in several Philadelphia hospitals for years.

Why?

Anesthesia's slow start

One would have assumed that once ether anesthesia was introduced, the surgical world would be overjoyed and embrace this transformative innovation with widespread immediacy. But the journey that ether anesthesia took was not that easy … and the reasons were surprisingly logical and diverse.

First, one must understand the mindset of mid-19th century surgeons. It was not just for the entirety of their careers that the norm was to perform surgeries on fully-conscious patients — the practice spanned the entire history of surgery. Speaking with, and attaining permission from, the patients on which they were operating had always been a part of the surgical process. To remove that interaction by using anesthesia seemed utterly foreign to them — like removing one of their senses.

Additionally, anesthesia was discovered in a time before standardized medicine. While the use of pharmacists was growing in popularity (doctors were less reliant on mixing their own medicines), there was no guaranteed quality when it came to medicine during this time period. Surgeons couldn't fully trust the ether they were using. Sometimes the mixture was too weak, and the patients wouldn't lose consciousness (or perhaps more horrifically, would regain consciousness mid-surgery). Other times, the mixture would be too strong, and the patient would die on the table from an overdose.

And lastly — and most compellingly for me — anesthesia was discovered before germ theory became understood as scientific fact. Physicians and surgeons during that time period still debated about whether the thorough washing of hands and tools prior to surgery was even necessary. Because of the lack of cleanliness in the operating room, deaths from surgeries were often not from bleeding out on the table, but from the horrific infections which would overcome the body once the surgery was completed.

The discovery of ether anesthesia certainly opened bold new possibilities when it came to the art of surgery, but without the antisepsis practices that would be embraced by later generations of doctors, the mortality rates for ether surgeries were not terribly different from the surgeries where the patient was thrashing on the table.

It was because of those factors, and other lesser ones, that the American medical community struggled to accept the leap in innovation that anesthesia promised. While doctors like Mütter embraced it — understanding that while it was not perfect, the positives far outweighed the negatives — other doctors were not convinced. For years after its discovery, hospitals and medical schools would continue to ban its use in their operating rooms.

Prestigious doctors and dentists would publish damning op-eds referring to the drug as "satanic influence," and decrying those doctors who supported its use by saying they had been "seduced from the high professional path of duty into the quagmire of quackery by this will-o'-the-wisp." And patients, in operating rooms and dentist's chairs across the country, would suffer unimaginably as the debate raged on.

Anesthesia becomes the norm

The true success — and the full acceptance — of anesthesia surgeries happened after so many other factors beyond its control aligned. Once germ theory was proven — and doctors insisted on sterilized environments, tools and hands in surgical settings — post-operative fatality rates plummeted. After the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was created and new legislation required pharmaceutical standards, doctors could feel more confident in the drugs they were administering. And once the old generation of doctors who knew no other way than performing on fully conscious patients died out, the principal voices of dissent were removed.

Science is often messier than people think — and scientific process can be even more messy. Anesthesia's path to acceptance reminded me of an illustration about the messy path of progress. One panel, "How People Think Success Happens" shows a humble line navigating a clean path upwards from a point marked "Obscurity" to a point marked "Success." The second panel, "The Reality of How Success Happens" contains the same two data points, but there is more line than paper, as the scribbled path is not clear at all, and for every hopeful rise there is a near-instant arch backwards and down.

It's important to remember that even if it takes time, progress does happen. And more often that not, it's a group effort. Every new discovery is just another piece of a larger puzzle that helps society create the platform for innovations yet to come.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus