Interbreeding Common? Ancient Human Had Neanderthal-Like Ear

The remains of an ancient human in China not thought to be Neanderthal has an inner ear much like that of humans' closest extinct relatives, according to a new study. These new findings could be evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and other species of archaic humans in China; however, the researchers say human evolution could be more complicated than is often thought, and the implications of the new discovery remain unclear.

Although modern humans are the only living members of the human family tree, a number of other human lineages once lived alongside the ancestors of modern humans. These so-called archaic humans included Neanderthals, the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, who lived in Eurasia roughly between 200,000 and 30,000 years ago.

To learn more about human evolution, scientists investigated a 100,000-year-old human skull known as Xujiayao 15, found 35 years ago in northern China alongside human teeth and bone fragments. At first, the researchers thought that the skull belonged to an archaic human. But they discovered that, anatomically, the skull — and the fossils discovered alongside it — had characteristics typical of a non-Neanderthal form of archaic human. [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

"It's clearly not modern human," said study co-author Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

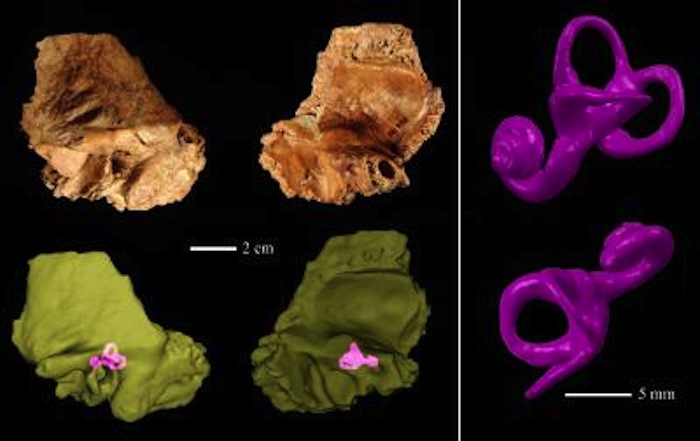

However, micro-CT scans of the skull revealed an inner ear much like those seen in Neanderthals.

"We were very surprised," Trinkaus told Live Science. "I said, 'My God, it looks like a Neanderthal.'"

The inner ear, also known as the labyrinth, is located within the skull's temporal bone. It contains the cochlea, which converts sound waves into electrical signals that are transmitted via nerves to the brain, and the semicircular canals, which help people keep their balance as they move. These semicircular canals are often well-preserved in mammal skull fossils, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the mid-1990s, CT scans revealed that nearly all Neanderthals possessed a specific arrangement of their semicircular canals. The pattern of semicircular canal sizes and positions seen in Neanderthals was often used to set them apart from both earlier and modern humans.

"We fully expected the scan to reveal a temporal labyrinth that looked much like a modern human one, but what we saw was clearly typical of a Neanderthal," Trinkaus said in a statement. In comparison, none of the three other archaic human skulls they analyzed from different parts of China had this type of inner ear.

But while it is tempting to conclude that these findings demonstrate interbreeding between Neanderthals and archaic humans in China, Trinkaus and his colleagues suggested that the implications of the Xujiayao discovery remain unclear.

"You can't rely on one anatomical feature or one piece of DNA as the basis for sweeping assumptions about the migrations of hominid species from one place to another," Trinkaus said in a statement.

Instead, "what these findings say to me are that characteristics were probably more varied in ancient human populations than we think," Trinkaus said. "We see characteristics mix and match in populations across the world nowadays, and I believe that characteristics shuffled back and forth in ancient human populations across the landscape over centuries and millennia. The idea of distinct, separate lineages in this time period in human evolution is meaningless — it was much more of a labyrinth than that."

It remains uncertain whether these differences in the inner ear would have led to any differences in balance or agility between modern humans and other human groups. "Eventually, someone might sort out the biological implications of these differences, if there are any," Trinkaus said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (July 7) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus