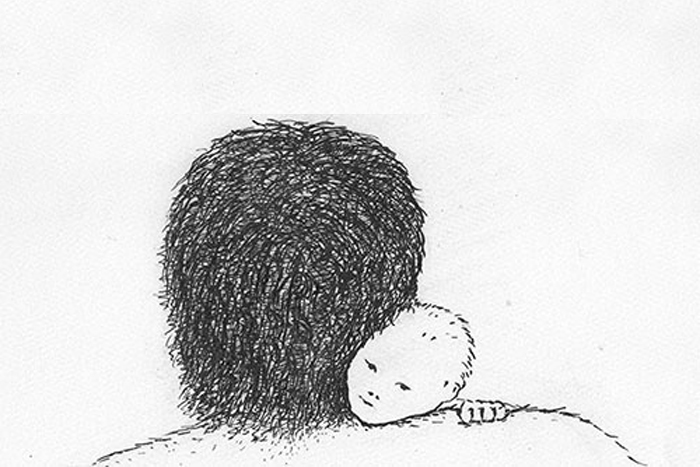

Cuddly Neanderthals With Parenting Skills

(ISNS)-- Neanderthals, the now-extinct cousins of modern humans, have a reputation of living lives that were brutal, primitive and short. They were apparently superseded by a more sophisticated species that became us.

Maybe not. Researchers from the University of York in England, studying burial practices of Neanderthals, particularly the bones of children and adolescents, say Neanderthal society was close-knit, caring and complex. Neanderthals made fine parents.

“Children may have been significant in Neanderthal society,” said Penny Spikins, senior lecturer in the archaeology of human origins at York and lead author of a paper in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology.

The York findings fly against the stereotype partly because most archaeologists ignored the bones of children found in Neanderthal graves. They pored over the bones of adults and stored the bones of children and infants in boxes in the basements of museums, never looking at them, Spikins said. But those bones and the graves in which they were found tell a story.

It’s now well known that because of interbreeding, Neanderthals were genetically similar to us. In modern humans of Asian and European origins, one to two percent of the genome came from Neanderthal ancestors. Their societies may have been similar as well.

They lived in small, relatively isolated families, having little contact with other groups. They lived lives similar to modern human hunter-gatherers in a cold environment. Think modern Inuit.

“There is a critical distinction to be made between a harsh childhood and a childhood lived in a harsh environment,” the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They cared for their children, teaching them what they needed to know. They also cared for the injured and sick, and when Neanderthals died -- particularly children and infants -- they were buried with care and respect.

The stereotype questioned whether Neanderthals even had childhoods. They did, the York researchers said.

“Children learned how to knap flint in the company of adults, so we can see the process where they are taught to do things,” Spikins said. They made toy axes. This not only taught them how to use the tools but instilled a social context.

Neanderthal children looked different when they were born. Neanderthals were structurally more robust than modern humans and looked more robust at birth, with a more prominent face and a “lower, wider, and more elongated brain case.” Their brains grew faster than do the brains of modern humans, and their bodies probably grew at a slightly faster rate, the scientists reported.

They reached physical adulthood at around age 15, slightly faster than modern humans. Most of the bones collected seemed to show a high mortality among juveniles, mostly from hunting accidents, but looking at all the evidence, the York researchers thought it does not support that conclusion, Spikins explained. Most of the skeletons were found in places where the Neanderthals lived, often caves. They died at home.

Many sick and injured had clearly been supported by their family members, sometimes for years.

Neanderthal infant corpses were the focus of explicit attention. More than a third of Neanderthal graves found contain children under the age of four, typically showing great care in their burials.

Some were buried with objects, including flint scrapers, a principle tool. Many had what appear to be ceremonial animal bones laid out carefully around the body. Even the places the bodies were buried showed care, often naturally occurring rock fissures or crevices.

Spikins said that when artifacts were found at Neanderthal graves, they most often were associated with the skeletons of children.

The graves showed strong evidence of a tight family structure. One group burial plot found in Spain held the remains of six adults -- three males and three females -- two juveniles and an infant, probably killed in a rockslide. DNA analysis showed they were related. The three males were brothers, and two of the children were the offspring of two of the females.

Their societies were “collaborative and cohesive,” the York researchers believe. They lived separate from other groups and tended to themselves, Spikins wrote.

Since higher primates like apes have games for children, there is no reason to think Neanderthals did not also have childhood games like peek-a-boo. The children probably felt secure within their family structure.

“They survived for hundreds of thousands of years, more than our own species has, and they only did that by working together,” Spikins said. They cared for each other and “these characteristics don’t come from being uncaring parents."

The research appears to vindicate the work of Joao Zilhao, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona, recognized as one of the Neanderthal's most fervent defenders.

“If Neanderthal had not been ‘loving parents,’ how would their offspring and hence the population itself, have survived?” he wrote in an email to Inside Science.

“The piece of news is not that a given study argues that such was the case. The piece of news is that such a case needs to be argued,” he wrote.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Joel Shurkin is a freelance writer based in Baltimore. He is the author of nine books on science and the history of science, and has taught science journalism at Stanford University, UC Santa Cruz and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He tweets at @shurkin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus