Coral Species May Adapt to Warmer Waters (Video)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Coral reefs tend to be vulnerable to damage from warmer waters, but at least one coral species may be able to adapt to the higher ocean temperatures that may come with climate change.

Researchers took branches of coral from tide pools of different temperatures and found that the branches taken from a warmer tide pool fared better in a heat-stress test than branches taken from a slightly cooler pool.

This shows that corals that live in warmer waters do develop a better ability than cooler-water corals to survive rising temperatures — a sign that corals can adapt over time to a changing environment, according to the researchers. [How Coral Strength Is Tested | Video]

"We found that [all] these coral colonies can adjust their physiology to become more heat-tolerant," said study author Stephen Palumbi, a professor at Stanford University.

"They [corals] do even better after they adjust their physiology if they have the right genes, but even if they don't have the right genes, their physiological adjustment gets them a nice bump in heat tolerance," Palumbi told Live Science.

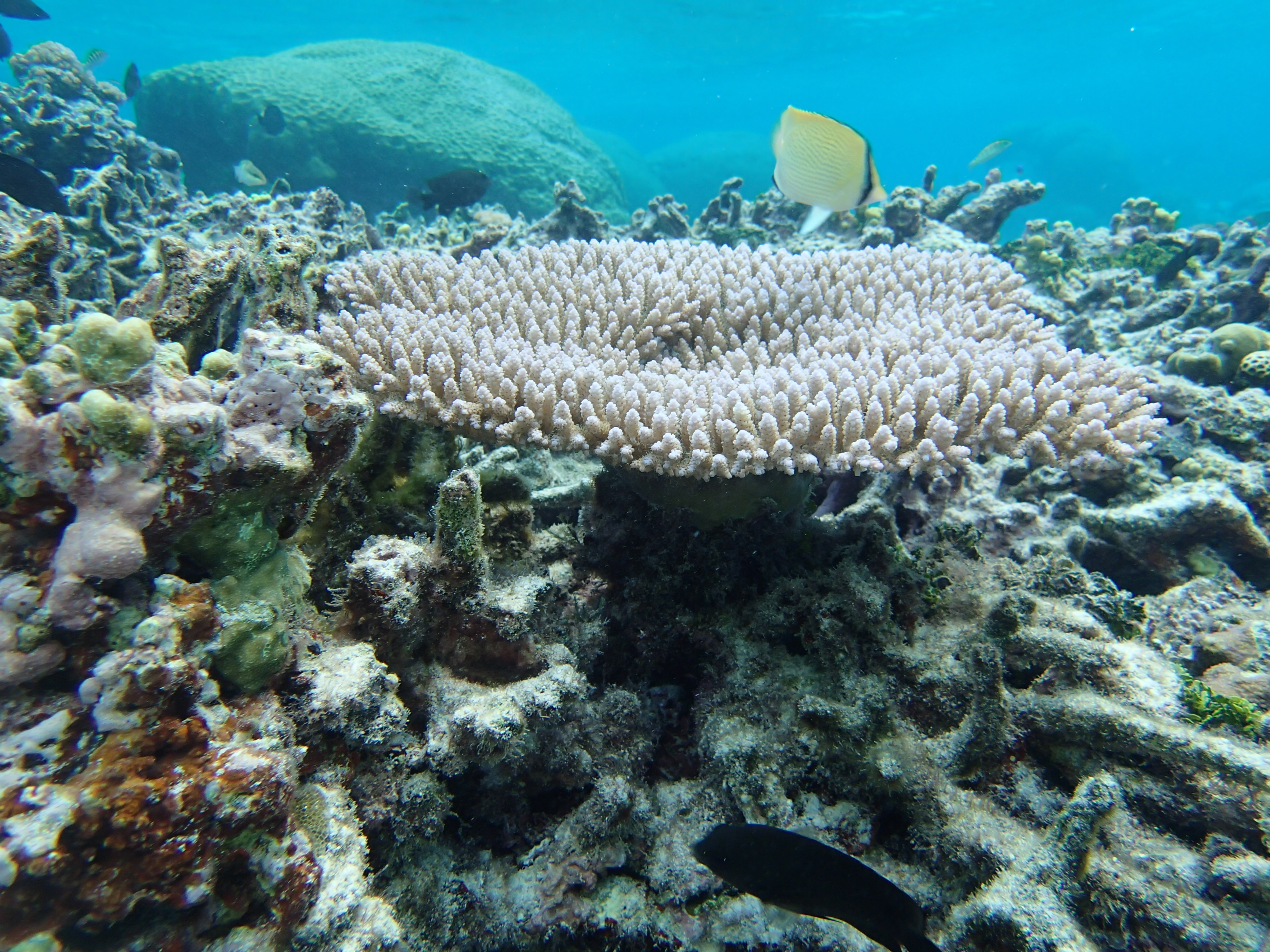

In the study, the researchers used branches of "table top" corals — which have a wide, flat shape — of a species called Acropora hyacinthus, known to be particularly sensitive to environmental changes.

When corals are exposed to considerably higher temperatures than the ones they are used to, they may expel their internal algae — the tiny, photosynthetic organisms that live within coral tissue — and then die, turning white in the process. This process is called coral bleaching and it is commonly considered the greatest threat to corals, especially in light of ocean warming predictions due to climate change.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The coral branches in the study came from two different tidal pools. The temperatures in the first, hotter pool were often higher than 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius), reaching up to 95 F (35 C), whereas the water in the second pool rarely exceeded 89.6 F (32 C).

The researchers subjected all the corals to temperatures that were much higher than what the corals were normally used to. After 27 months the research team checked the corals' resistance to heat by looking at their level of bleaching.

"All the colonies we moved showed an adjustment," Palumbi said. However, the corals that were initially in the hotter pool were more resistant than the other coral group, he said.

"We were able to show that corals that live naturally in a warmer environment have the right genes to be able to do even better in that warmer environment," Palumbi said. "But even the cold-water living corals had the ability to adjust their physiology to be more heat-tolerant," he said.

Researchers are not yet sure whether the same adaptation ability might be present in other coral species, Palumbi said.

While the physiological adjustment of corals happens fast, within one or two years, the evolution of the genes that allow corals to be more heat-resistant is a much slower process.

"We have no idea, from these studies, how far the physiology can go," and at some point corals may reach their limit of temperature adjustment, Palumbi said.

"So it is not like this physiological mechanism is a perfect way for corals to gleefully march ahead of climate change," he said.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus