Fecal Transplant Regulations Too Strict, Some Say

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

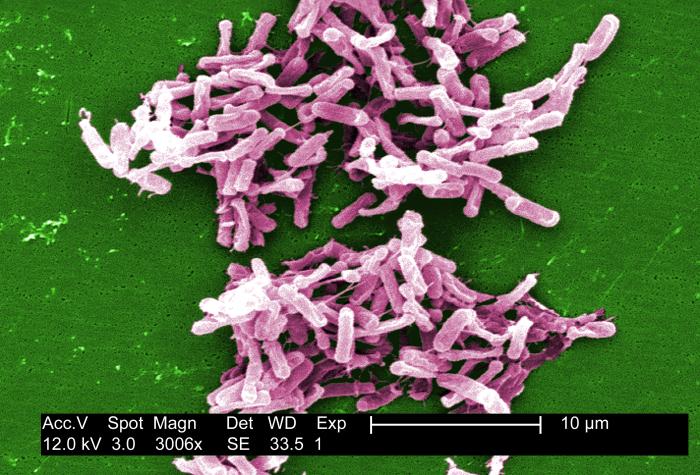

Physicians use fecal transplants to treat certain intestinal infections, but the procedures recently came under strict regulations, with the Food and Drug Administration managing the transplants as though they were a drug treatment.

This regulation has made it harder for patients to receive fecal transplants, and in a new paper, some researchers are calling for the transplants to instead be regulated as a tissue, akin to blood donations.

The raw material for fecal transplants isn't hard to come by, and so in the face of what some see as current over-regulation, an underground market for the transplants will likely spring up, the researchers argued today (Feb. 19) in the journal Nature.

At the same time, they said, more research is needed on the long-term effects of fecal transplants.

Regulating fecal transplants as a tissue may allow for better research on their possible uses in treatments, while protecting patients from harm, the researchers, from MIT and Brown University, wrote. [9 Most Interesting Transplants]

"I think regulating it as a tissue product would both provide access as needed and the research that could bring some pretty exciting new treatments on the scene," said Mark B. Smith, an author of the article and a doctoral candidate at MIT.

Fecal transplants have been tested since the 1950s, and last year the first randomized controlled trial showed a strong benefit in helping patients with recurrent C. difficile, a bacterial infection that causes painful diarrhea, often following the use of antibiotics, and kills 14,000 people yearly in the United States.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But following the treatment's success, some doctors began offering fecal transplants for other conditions as well — including those for which any potential benefit remains unproven. The FDA took action in 2013, regulating the treatment, but also granting an exemption for its continued use in patients who had C. difficile infections. This use would not require special permissions.

However, the result may be a case of both under- and over-regulation, today's editorial argues. While medical societies have issued guidelines for using the treatment, there are no hard and fast rules for screening fecal matter, as there are with blood donations.

And while other treatments remain unproven, Smith said there needs to be more research into what other conditions the procedure may be able to treat.

"It's not like the FDA has to worry about someone manufacturing Lipitor in their basement," he told Live Science. "[But] everyone's manufacturing this, everyday."

Smith said he became interested in the topic when a family friend, frustrated with not being able to find a physician to provide a fecal transplant, got a donation and performed an enema on himself.

For now, Smith has attempted one solution, by cofounding a stool bank near MIT, called OpenBiome.

"For the short term, we really need to make sure this material is available for patients who have recurring Clostridium difficile infection, who are literally dying without" the treatment, said Dr. Tom Moore, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Kansas, Wichita, who was not involved in writing the editorial. "I certainly endorse the reclassification or regulation of stool as a tissue product, rather than a drug."

A key step going forward will be finding donors who don't have infections, and who have never taken antibiotics, either, Moore said. Antibiotics can kill the "good" bacteria within a healthy gut. These individuals may have more ideal bacterial communities in their guts, he said.

"This is an agent which varies significantly from person to person in terms of its makeup of various microbes," Moore said. "We know to some extent what's in it, [but] we don't know what's in it from person to person."

Dr. Ravi Kamepalli, an infectious disease physician in Lima, Ohio, expressed some skepticism about further regulation from the FDA on transplants for C. diff., noting that as long as current guidelines are followed, more review might prevent patients from getting needed treatment. However, he added, more research needs to be done to evaluate the long-term risks.

For now, he said, a major problem is finding a knowledgeable physician willing to perform the treatment.

"It is physician acceptance that is the wider obstacle," Kamepalli said.

Follow Joe Brownstein @joebrownstein. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus