Eye Cells Inkjet-Printed for First Time

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Using an inkjet printer, researchers have succeeded in printing adult eye cells for the first time. The demonstration is a step toward producing tissue implants that could cure some types of blindness.

Scientists have previously printed embryonic stem cells and other immature cells. But scientists had thought adult cells might be too fragile to print. Now, researchers have printed cells from the optic nerves of rats, finding the cells not only survived, but also retained the ability to grow and develop.

The loss of nerve cells in the retina causes many eye diseases that lead to blindness, said Dr. Keith Martin, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cambridge, in England, and co-author of the study detailed online today (Dec. 17) in the journal Biofabrication. The work is preliminary, but eventually, the aim is to be able to print a replacement retina, Martin told LiveScience. [7 Cool Uses of 3D Printing in Medicine]

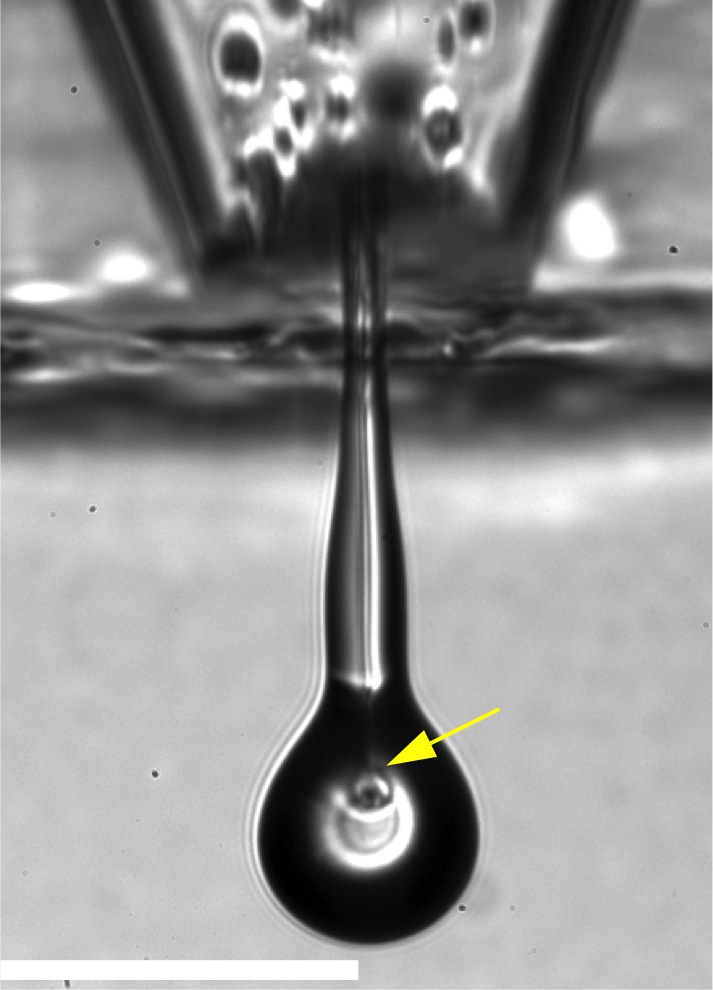

Martin and his colleagues separated retinal ganglion cells (which transmit signals from the eye to the brain) and glial cells (which provide support and protection for neurons) from the retinal tissue of adult rats. They used a piezoelectric inkjet printer to print both types of cells into a vial at a rate of about 30 mph, or about 100 cells per second, recording the process with high-speed video. Then they performed tests to see how well the printed cells survived and grew.

Despite the shearing forces the cells experienced during printing, the printed retinal ganglion cells (also called optic nerve cells) and the glial cells appeared to survive as well as nonprinted cells. In addition, the optic nerve cells retained the ability to sprout neurites, the fingerlike filaments that form connections with other nerve cells.

"The printed cells were indistinguishable from cells that hadn’t been printed," Martin said. The researchers also printed the optic nerve cells onto a plate of glial cells, and this increased the growth of neurites.

However, the printed sample had fewer of both kinds of cells than the unprinted sample, and the researchers think this is because some of the cells got stuck in the printer nozzle.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Testing that the cells function like healthy optic nerve cells will be crucial, and these studies are currently underway, Martin said.

Now that the scientists have shown they can print retinal ganglion cells, they plan to print other types of retinal cells, such as light-sensitive photoreceptors. They also plan to print cells in patterns, and adapt the technology for commercial multinozzle print heads.

The work was partially funded by Fight for Sight, a nonprofit organization that supports new treatments for blindness.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus