Just 2 Genes from Y Chromosome Needed for Male Reproduction

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Y chromosome is often thought of as defining the male sex. Now scientists find that only two genes on the Y chromosome are needed in mice for them to father offspring.

These findings could point to ways to help otherwise infertile men have children, the researchers said. Men with a condition called azoospermia, who cannot produce healthy sperms cells, could one day benefit from treatments based on these findings, they said.

In the study, researchers injected two Y-chromosome genes into mouse embryos that lacked a Y chromosome, and found the embryos grew into adult mice that could produce offspring — not through the typical get-together with a female mouse, but through assisted reproduction techniques.

"Only two Y-chromosome genes are needed to have children with the help of assisted reproduction," study author Monika Ward, a reproductive biologist at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu, told LiveScience. The scientists detailed their findings online today (Nov. 21) in the journal Science. [Sexy Swimmers: 7 Facts About Sperm]

Past research showed that when a gene called Sry was inserted into mouse embryos that are genetically female, "it changed the fate of the mice," Ward told LiveScience. "Even though they had two X chromosomes, they developed into males."

These mice developed testicles and produced sperm precursor cells known as spermatogonia; however, these cells did not develop into sperm cells.

In the new work, the researchers added other Y-chromosome genes, one at a time, into such mice. The trial-and-error process eventually revealed a gene called Eif2s3y helped spermatogonia occasionally develop into spermatids, or immature sperm.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spermatids are round cells, lacking the whiplike tails that mature sperm use to swim toward and fertilize egg cells. This means that although mice with Sry and Eif2s3y are male and can generate sex cells, they cannot normally have offspring.

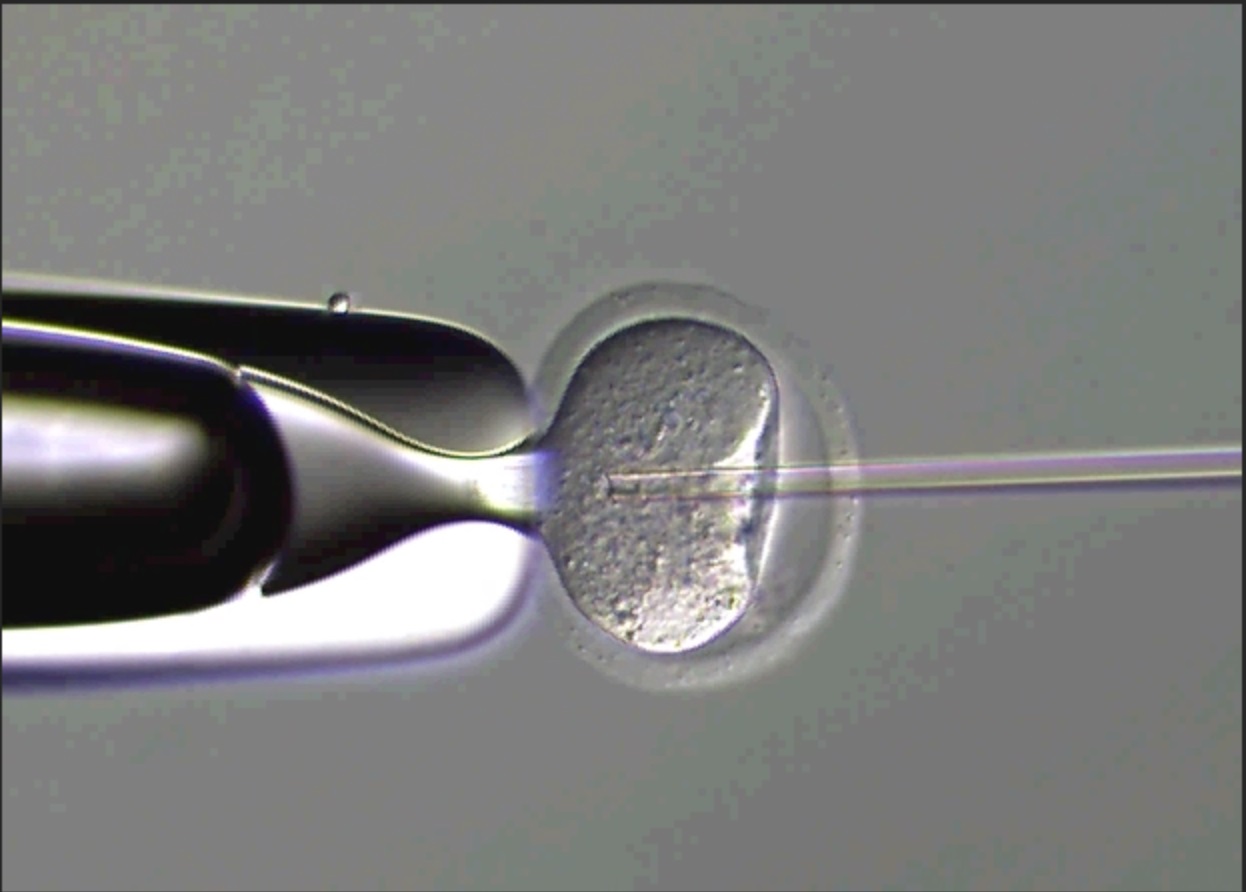

To see if males with this pair of Y genes could reproduce with a little help, Ward and her colleagues injected these spermatids directly into egg cells. They found they could successfully fertilize the eggs with this method, resulting in viable offspring.

The researchers emphasized the whole Y chromosome is likely needed for normal reproduction — its other genes help mature sperm develop.

"We're not trying to eliminate Y chromosomes with our work — or men, for that matter," Ward told LiveScience. "We're just trying to understand how much of the Y chromosome is needed, and for what."

The female offspring resulting from this method of reproduction were fertile, capable of giving birth to healthy young. The researchers did not test if the males resulting from this method also could have viable offspring — presumably, these males would not be able to have progeny the conventional way, but their spermatids may also be capable of fertilizing eggs if they were injected directly into them, Ward said.

The researchers noted these findings may not hold up in humans. Still, Ward said the success of spermatid injection seen in this work could support it as an option for overcoming infertility in men in the future.

"It could offer otherwise infertile men the possibility of fathering children," Ward said.

The scientists now want to see how many Y genes are needed to generate mature sperm that could fertilize eggs without assistance. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus