Haitian Cholera Epidemic Continues to Kill Elsewhere

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Since a cholera epidemic began in Haiti in 2010, the disease has killed more than 8,300 people in that country. The bacteria that cause cholera may be settling in for good in Haiti, and meanwhile, its swath of destruction appears to be widening to other countries, researchers reported here Sunday (Nov. 3).

United Nations Peacekeepers from Nepal stationed in Haiti appear to have introduced the strain of the bacterium responsible for the epidemic through untreated sewage from their camp. This strain has since begun infecting and killing people in the Dominican Republic, Cuba and most recently, Mexico, health organizations report. Advocates for Haitian cholera victims have said they will sue the United Nations to force the international organization to admit responsibility for the epidemic, The New York Times reported.

The cholera epidemic that surfaced in October 2010 was the first to hit Haiti during modern times, but now appears unlikely to be the last, Dr. Glenn Morris, director of the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida, said during a presentation on Sunday (Nov. 3).

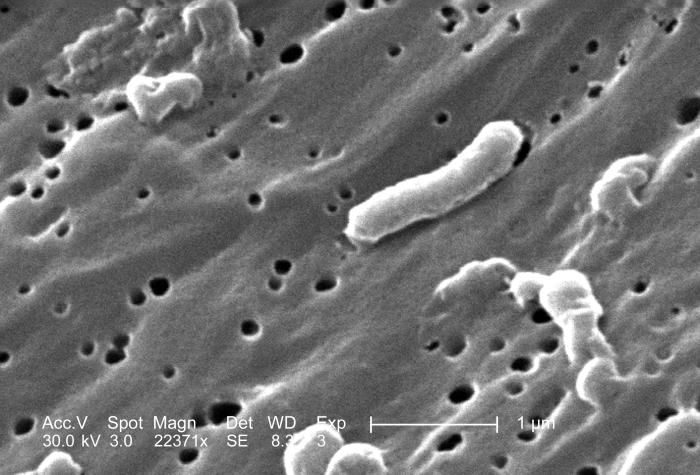

The cholera bacterium, Vibrio cholera, lives in water, particularly in estuaries or slightly salty aquatic environments. Under the right conditions, such as warm temperatures, these bacteria multiply and infect people who use the water. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

It appears that this strain of cholera may be staying in Haiti permanently, Morris said.

"What we find is the bacteria does appear to be taking up residence within the environment," he said. "That means what we are seeing is not a one-shot thing, but something that will keep happening."

Historical records indicate cholera has been with humans for at least a millennium. The strains circulating now likely originated from a bacterium in Asia's Bay of Bengal region in the 1950s. Since then, the pathogens spread out in three waves, according to research reported in the journal Nature in 2011.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In many ways, it's a simple disease," Morris said. Cholera causes severe diarrhea, which leads to dangerous dehydration and potentially death. But it is easy to treat. A fluid mixture containing salt and sugar is used to replace 1.5 times the volume of diarrhea, he said.

On Oct. 28, the World Health Organization reported 176 confirmed cases of cholera, including one death in Mexico caused by the strain from Haiti. In Cuba, the Pan American Health Organization has reported 678 confirmed cholera cases, including three deaths, and authorities in the Dominican Republic have reported 31,021 confirmed cases, including 456 deaths.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus