Shutdown Could Flush Years of Antarctic Research Down the Drain

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than 10 years of planning, $10 million of government funding and tireless work from the team that discovered life in a lake buried beneath an Antarctic glacier earlier this year may largely go to waste due to the government shutdown.

The WISSARD drilling program — a collaborative effort of 14 principal investigators including glaciologists, geophysicists, microbiologists and others from nine institutions across the country — is one of the largest programs ever fielded by the U.S. Antarctic Program.

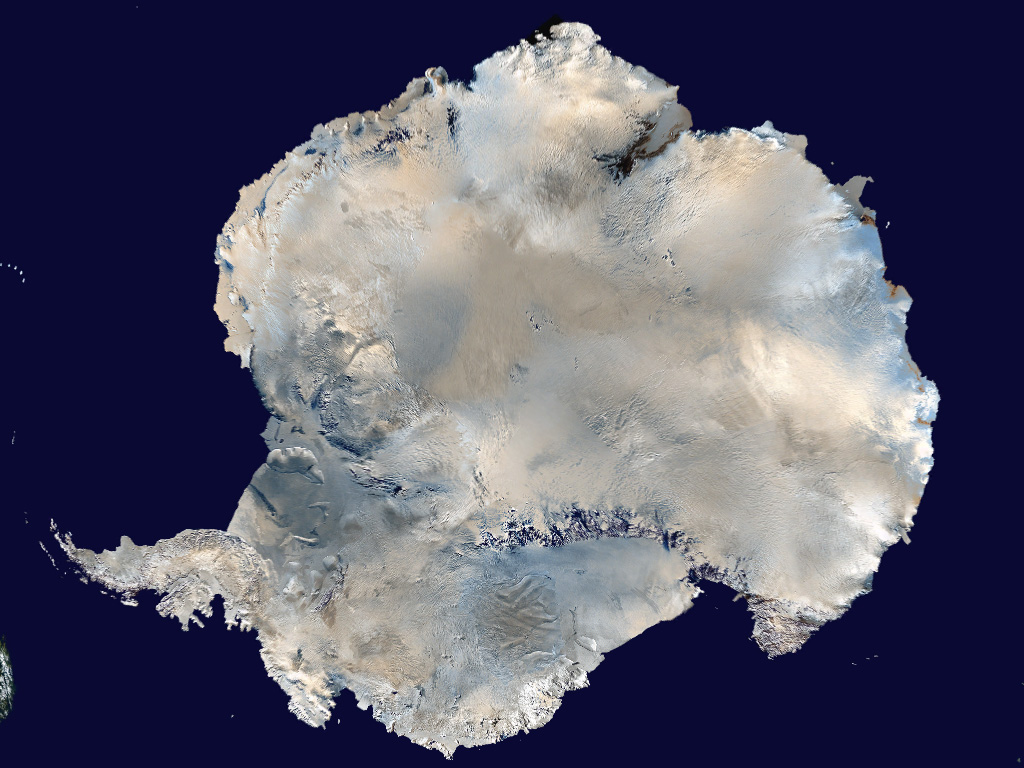

The team consists of more than 50 scientists, graduate students and support staff members, who aim to explore the underbelly of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet— a flowing mass of ice about the size of France — in order to study its dynamics and improve models that predict its melting rate. If it were to melt completely, the ice sheet would increase average global sea level by between 10 to 16 feet (3 to 5 meters).

The National Science Foundation funded WISSARD in 2009 with stimulus money, providing enough resources to complete two field seasons during the Southern Hemisphere summers of 2012-2013 and 2013-2014.

Last year, the team drilled the first ever hole into a lake buried under roughly half a mile (0.8 kilometers) of ice. Researchers discovered microbial life within this remote environment, and deployed a series of environmental sensors that would measure temperature and other conditions through the following year. [Antarctic Album: Drilling Into Subglacial Lake Whillans]

For the second and final field season, scheduled for this December through early February, the team planned to collect those data loggers and drill a new hole into the grounding zone of the glacier, where the glacier's base meets the sea. This would be the first hole ever drilled into a glacial grounding zone, a region that largely controls the stability of the ice sheet and the rate at which it flows into the sea and increases sea level.

Science in jeopardy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the National Science Foundation announced this week that it would cancel its entire U.S. Antarctic research program until the shutdown ends, jeopardizing the entire second half of the WISSARD program.

"It's heartbreaking," said Slawek Tulaczyk, a glaciologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a principal investigator with WISSARD. "So many people put in their time, their passion into making sure that this happens. It takes a lot of professional, dedicated work."

Tulaczyk's team has worked through many weekends over the past three months preparing to ship scientific equipment — some of which they spent years designing specifically for this year's work — down to Antarctica to ensure that it arrives in time for their field season.

Those shipments have now stopped en route, and likely won't arrive in Antarctica by mid-November as had been scheduled.

"If we can't get stuff into the field on time, then there is no reason to see it forward," Tulaczyk told LiveScience.

The team cannot postpone the season and push it forward, because they need a full two-and-a-half months to achieve their goals, and because pushing the season further into February would pose serious safety risks: By late summer, temperatures drop well below 10 degrees Fahrenheit (12 degrees below zero Celsius), winds pick up, the sun sets earlier and search and rescue teams do not have enough visibility in the featureless white expanse of the continent to safely access emergencies.

"There is a hard deadline after which we cannot delay, because it just becomes unsafe for the personnel," Tulaczyk said.

Uncertain future

The funding for the project ends in 2014, so the team would need special permission from the government to extend the project through 2015, which Tulaczyk said might be possible but seems unlikely.

Graduate students whose dissertations depend on this year's data are considering discontinuing their graduate programs, said John Priscu, a researcher at Montana State University and the principal investigator studying the newly discovered microbial life underneath the glacier.

"The loss of graduate student field work will diminish our efforts to train the next generation of polar scientists," Priscu said. [Image Gallery: Back-Breaking Science at the Earth's Poles]

Tulaczyk also pointed out that personnel at the research base, whose decades of field experience allow operations to run safely and effectively, may now lose their jobs.

"People who have been going down for decades and have a really unique skill set are faced with being laid off within a couple of days now," Tulaczyk said. "You can't go out and replace someone who has so much experience."

Tulaczyk said this series of events may cause his graduate students to question if science was the right investment for them to make with their lives. It's not the loss of one field season that makes the difference, he said, but the years of preparation and coordination that may now go to waste.

"This undermines the next generation of people," Tulaczyk said. "It is really complicated. It will impact things for years to come."

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus