Infected and Hunched: King Richard III Was Crawling With Roundworms

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

William Shakespeare depicted King Richard III as a crooked ruler, due to the monarch's supposed ruthless demeanor and his curved spine. A new study suggests that in addition to scoliosis, Richard III suffered from a roundworm infection.

Interest and research into the monarch has spiked since scientists found Richard III's skeleton beneath a parking lot in Leicester, England. It was first uncovered in September 2012, and its identity was confirmed via DNA testing earlier this year.

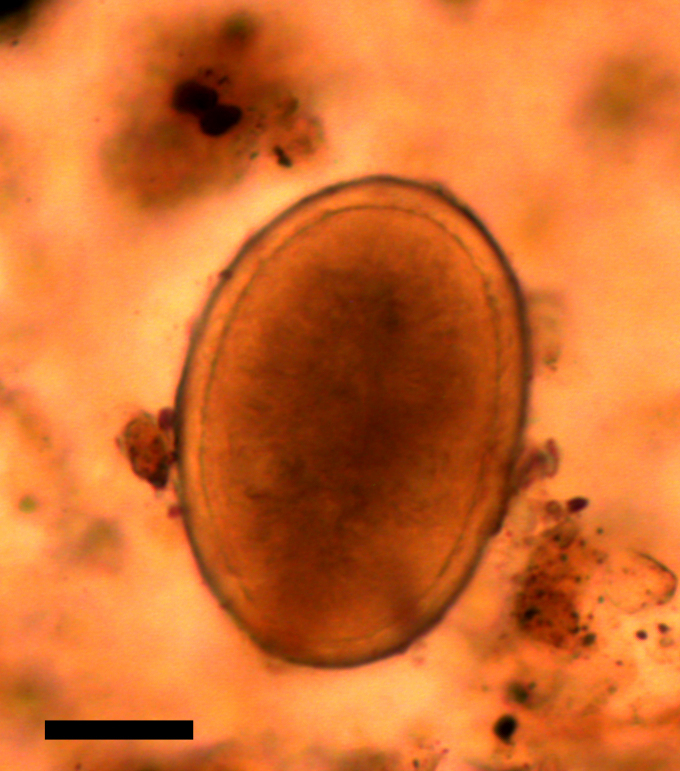

While digging up the bones of Richard III, who was born in 1452 and ruled England from 1483 to 1485, scientists took soil samples from within the grave. They then looked for evidence of parasites in order to better understand his health and diet. Within the soil where the king's pelvis once rested, they found a large number of ancient eggs from roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides). As a control, they also took a soil sample from inside Richard III's skull and from the grave outside the bounds of the body. They found no eggs in the skull sample, and only a small number — 15 times fewer eggs — in that soil, suggesting a background level of contamination from sewage, said Piers Mitchell, a physician and biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge. [Photos: the Search for Richard III's Grave]

Proof of worms

"I would say this is 100 percent proof that he had a roundworm infection," because there "is no other explanation" for the large amount of roundworms found where his intestines once lay, Mitchell told LiveScience. A study detailing the finding was published today (Sep. 3) in the journal The Lancet.

The scientists found zero trace of other types of parasites also recorded in England at the time, such as whipworms or liver flukes. Nor did they find signs of pork, beef or fish tapeworm. The king ate all of these foods, according to a forthcoming analysis of the chemical content of his bones and preserved menus from monarchs of this time period, so this lack of other parasites suggests the king's food was well cooked, Mitchell said.

Roundworms live in human intestines and are spread via fecal material, such as when people come into contact with eggs in feces and don't wash their hands before cooking, Mitchell said. Roundworms can also be spread when contaminated sewage is used to fertilize crops. Roundworm infections are now rare in the United Kingdom and much of the developed world, but they remain common in the developing world, especially near the equator; the animals thrive in warm and moist environments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cut short

Once a person is infected with roundworm, larval worms make their way to the lungs and crawl into the airways, where they mature for about two weeks, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They then make their way to the esophagus and are swallowed, further maturing in the intestines and growing to more than 1 foot (30 centimeters) long.

It's unclear how much the roundworm infection may have affected King Richard III, who was said to be a ruthless and power-hungry man, Mitchell said. Doctors were familiar with certain parasitic worms during these times and thought such infections were due to an imbalance of humors or bodily fluids, he said. Thus, a hypothetical treatment (had Richard's doctors been alerted to the presence of eggs in his stool) likely would have involved bloodletting and a diet of warm, dry food, he added.

King Richard III's reign was cut short when he was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field, the main battle in the English civil war known as the War of the Roses. Richard's skull still sports a mark left from a blade injury suffered during the battle, and a metal arrowhead was found lodged among the vertebrae of his upper back.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus