Spy Satellite Data Reveal Antarctic Ice Vulnerability

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

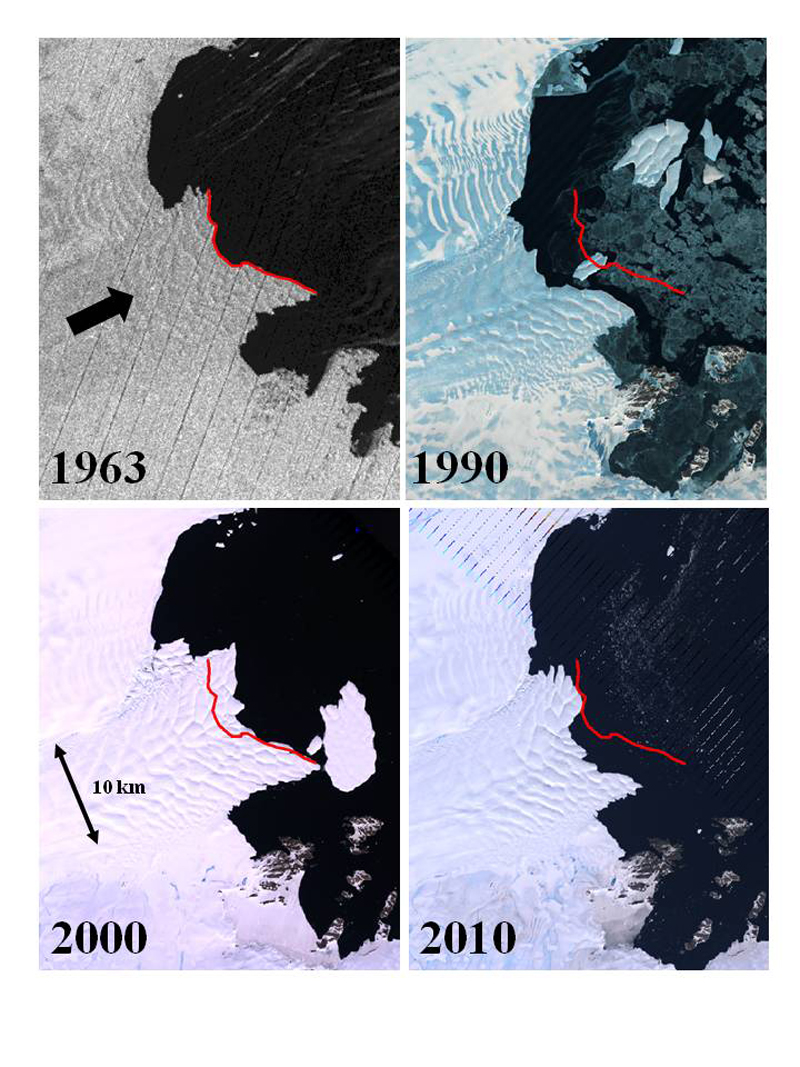

Declassified spy satellite imagery of Antarctica dating back to the 1960s has revealed that the world's largest ice sheet may be more susceptible to climate change than once thought.

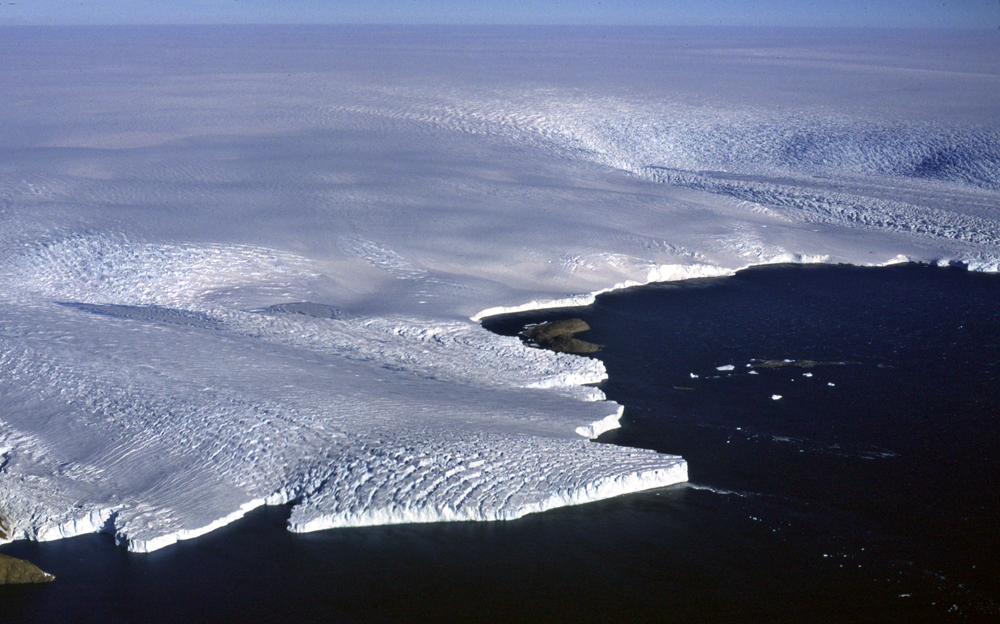

East Antarctica reaches higher elevations than elsewhere on the continent and experiences some of the coldest temperatures on Earth, hitting well below zero degrees Fahrenheit throughout much of the year. As a result, a massive ice sheet has accumulated, measuring more than 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) thick in some regions, holding enough water to raise global sea level by more than 160 feet (50 meters) if it were to completely melt.

Due to its thickness and high elevation, researchers have regarded the East Antarctic Ice Sheet as relatively stable and more resilient against climate change than the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which sits much closer to sea level and experiences warmer average temperatures.

Glacier growth and retreat

Now, researchers from Durham University in the United Kingdom have used declassified spy satellite imagery covering the years from 1963 to 2012 to study changes in the outer margin of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, and have compared these patterns with climate data from the region. The team has found that periods of expansion and retreat of the ice sheet's glaciers, essentially rivers of ice, appear to correspond with periods of warming and cooling in the atmosphere within the past 50 years. [Gallery: Scientists at the Ends of the Earth]

"We've shown for the first time that these glaciers are in concert with climate," Chris Stokes, a professor of geography at Durham University and an author of the paper, told LiveScience. "So the concern would be that if it does start to get warmer, then we would expect to see the glacier retreat."

While the researchers did note periods of growth and retreat, they did not detect a notable net change in the size of the ice sheet during the study period. Future warming could, however, push the region into a more significant retreat phase that could potentially cause net reduction in ice thickness in the region, Stokes said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Isolated area

Since East Antarctica is so isolated and difficult to access compared to coastal regions of West Antarctica and areas around the North Pole, fewer climate monitoring stations have been established there, and less data is available on ice sheet dynamics in the region. As a result, the interplay of climate and glacial patterns remains relatively poorly understood. The scientists hope that, in the future, they will be able to more closely assess these dynamics by culling together and examining other available satellite and climate data. [The Harshest Environments on Earth]

"All we have done is a quick health check," Stokes said. "What we want to do now is work out how fast the glaciers are flowing and how deep they are."

The new findings appear today (Aug. 28) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus