Digging Up the Truth: 1906 Earthquake Mystery Solved

In 1906, a giant San Andreas Fault earthquake carved a trench through Portola Valley, now a small California village of million-dollar homes tucked in the hills above Stanford University.

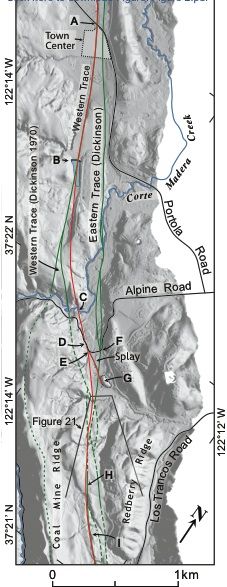

More than a century later, geologists believe they've proved the San Andreas Fault plowed alongside the valley's western ridges, ending decades of debate caused by a poorly reproduced historic map.

"We really didn't understand why there could be this level of confusion as to what happened in the great earthquake when right near here there was Stanford University," said Ted Sayre, the Portola Valley town geologist who is a consultant with the firm Cotton, Shires & Associates Inc. "There should have been a good record of what really happened."

Errors compounded

In the aftermath of the devastating magnitude-7.7 earthquake that destroyed San Francisco, Stanford geologists set out on horseback to survey the local damage. The scientists photographed the damage and produced an exquisitely hand-drawn map, all of which still exist in historic archives. [Album: The Great San Francisco Earthquake]

But 1908 reproductions of the map were less than clear. Through the decades, errors grew with each new geologic map of Portola Valley, Sayre said. Adding to the confusion are the San Andreas Fault's several parallel traces in the valley.

Like many big strike-slip faults, the San Andreas can be a braid or a single thread. Sometimes the fault is a zone of several smaller faults, one or more of which may break during an earthquake. (Strike-slip faults move each side of the fault mostly parallel to each other, along the nearly vertical fault.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In Portola Valley, two fault strands weave under the west and east sides of the valley. For decades, local geologists have debated whether the 1906 earthquake skipped across the valley, jumping from west to east and back west again as it raced northward, or if it just stayed on one strand, Sayre said. (Before Portola Valley's housing prices went sky-high, the village was a popular home for U.S. Geological Survey employees at nearby Menlo Park.)

Historic to high-tech

To finally settle the west-versus-east debate, Chester Wrucke, a former U.S. Geological Survey geologist, and his son Robert Wrucke, dug up the original Stanford earthquake map and photos. Chester Wrucke lives in Portola Valley, not far from where the San Andreas Fault's newly found location crosses Alpine Road. Working with town geologist Sayre, the trio of sleuths compared the 1906 photos to publicly available bare-earth lidar imagery of the valley, tracing the historic ruptures onto the modern topography. Bare-earth lidar is an airborne laser measurement technique that results in finely detailed topography, free of trees and brush.

The research confirms that only the western fault strand broke in the 1906 earthquake, and verifies its location, Sayre said. The results were published Aug. 1 in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Although both the western and eastern branches of the San Andreas Fault are considered active in Portola Valley, as defined by California state law, knowing the precise location of the most recently ruptured strand is vital for avoiding new construction on top of the fault, Sayre said. California's Alquist-Priolo Act prohibits building structures for human occupancy on top of active faults.

"Our primary concern is another rupture on the 1906 trace," Sayre said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Most Popular