In Images: How North America Grew As a Continent

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Creating a continent

The landmass called North America is actually pretty young, becoming something close to its current incarnation less than 200 million years ago. Before then, the continent was called Laurentia on its journey back and forth across the equator, as it joined and was separated from supercontinents. Over billions of years, whether Laurentia or North America, the continent took its form through many spectacular collisions and massive rifts. Here's a walk through the geologic history of North America.

Prehistory

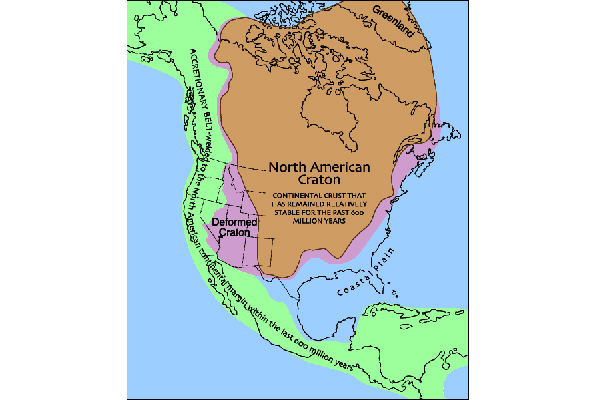

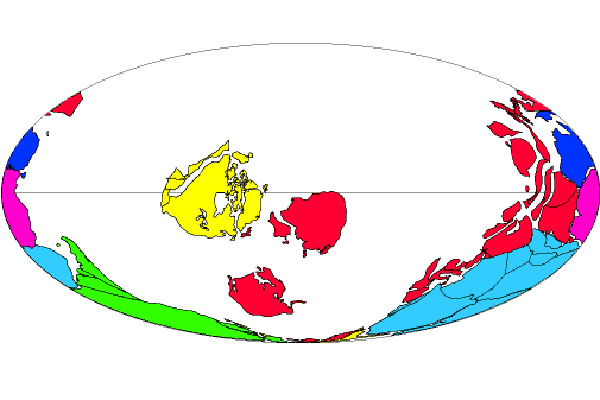

The central core of present-day North America is its craton, the oldest, thickest part of the continent. While parts of the craton peek out in Greenland and Canada, in the U.S., thick layers of sedimentary rocks keep most of these ancient assemblages under wraps in the center of the continent. The rocks here are more than two billion years old in places, andwere assembled through time as smaller microcontinents and terranes, or fragments of crustal material, crashed together. About 750 million years ago, the craton, then named Laurentia, was part of a supercontinent called Rodinia. After Rodinia fragment, Laurentia drifted almost to the South Pole!

A brief respite

By 542 million years ago, when complex life forms suddenly appear in the fossil record all across the planet, Laurentia was surrounded by ocean and passive margins on all sides. Like today's East Coast, a passive margin has no active collision or boundary between two of Earth's tectonic plates.

Mountain building

The continent's brief Cambrian respite ended in the Ordovician, when an island chain slammed into the East Coast, raising mountains from Greenland to Mississippi . At the time, the Appalachians were as tall and stunning as the Himalayas are today.

A similar collision in the Southwest about 370 million years ago twisted rocks throughout what is now Utah and Nevada.

Supercontinent!

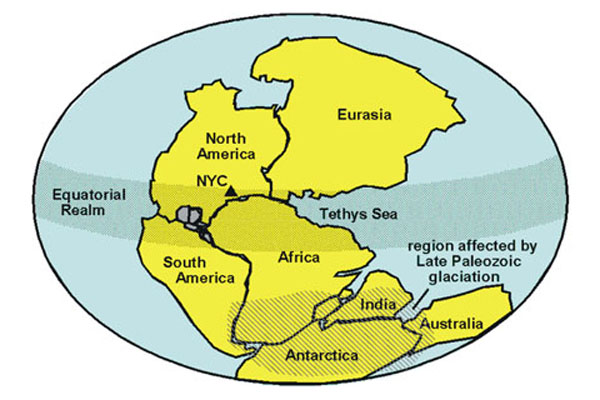

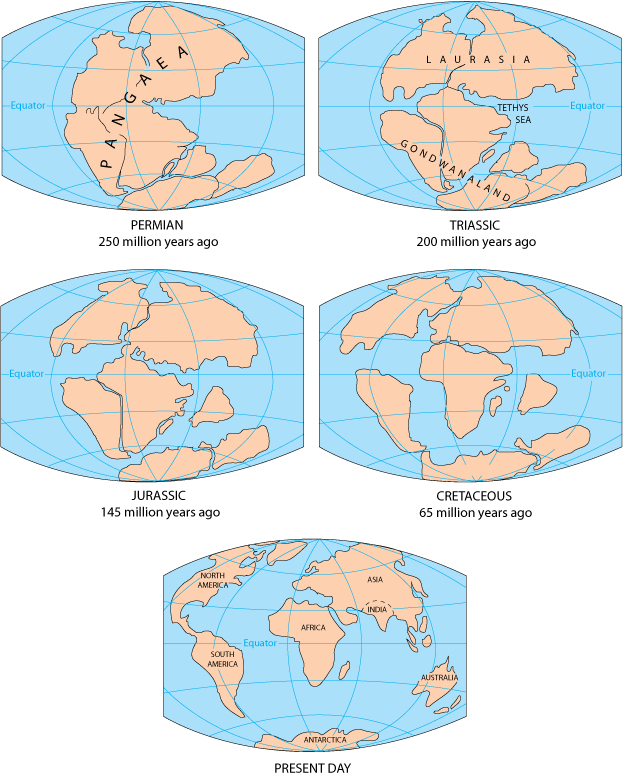

The supercontinent Pangaea included almost every giant landmass on Earth. As these pieces of continent crashed together 300 million years ago, mountains continued to rise along what is now the East Coast.

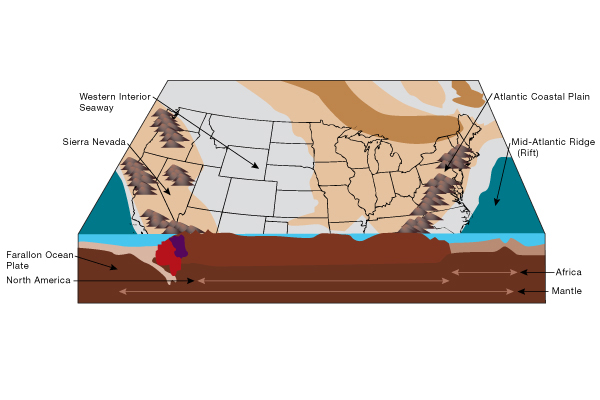

Birth of North America

The Atlantic Ocean opened 200 million years ago, pushing North America westward. As the continent rifted away from the supercontinent Pangaea, it finally earned the name North America.

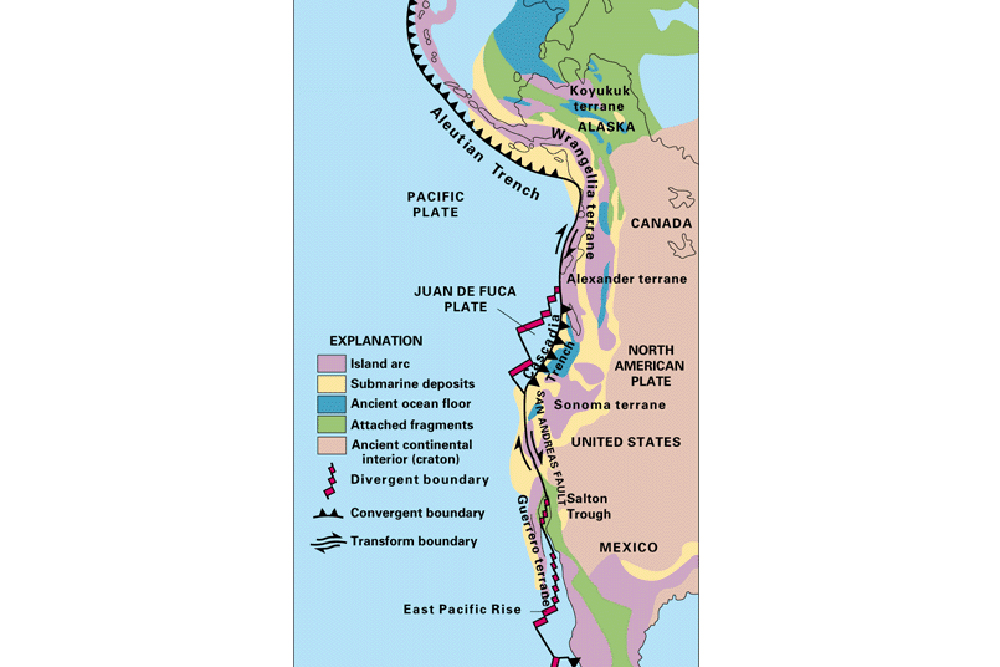

Building the West

As the East Coast settled down into a passive margin, with no active tectonics, things were heating up in the West. The widening Atlantic Ocean pushed the continent over the Panthalassa Ocean, precursor to today's Pacific. Geoscientists debate the timing and position of subduction zones along western North America. Did it look like today's Andes or like Southeast Asia? Either way, oceanic crust started to disappear as the continent shifted around. Exotic island chains slammed into the western edge, adding to North America's breadth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

San Andreas starts up

When North America gobbled up the boundary between the Farallon and Pacific oceanic plates, its western margin shifted from a subduction zone to a transform boundary. This marks the beginning of the San Andreas Fault, which moves side-by-side. With the sudden shutdown of the giant conveyor belt grinding against its margin, the continent relaxed, and the Basin and Range province opened in the Southwest. The last little bits of the Farallon plate remain off the Washington and Oregon coast, and further south, near Central America.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus