The First (and Last) Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

A half-century ago, humanity arrived somewhere no one had ever gone before the deepest place on Earth.

Before the Apollo missions landed men on the moon, the U.S. Navy dove to the bottom of the sea the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, some 35,797 feet (10,911 meters) down.

Just as no one has visited the moon since Apollo, nobody has returned to this abyss since that first voyage to the bottom of the trench in 1960. However, just as scientists are revisiting the moon with space probes, so too are researchers now deploying robots to explore this deepest depth of the ocean .

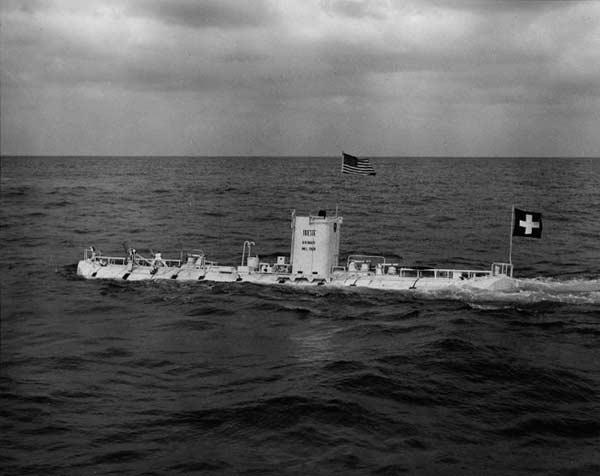

The research vessel used to reach the record-setting depth near Guam in the Pacific Ocean on Jan. 23, 1960 was named the Trieste, a Swiss-designed bathyscaphe or "deep boat" named after the Italian city where much of it was built. Its two-man crew Lt. Don Walsh of the U.S. Navy and scientist Jacques Piccard, son of the craft's designer nestled inside a roughly 6.5-foot (2-meter) wide white pressure sphere on the underside of the submersible. The rest of the nearly 60-foot (18-meter)long Trieste was filled with floats loaded with some 33,350 gallons (126,243 liters) of gasoline for buoyancy, along with nine tons of iron pellets to weigh it down.

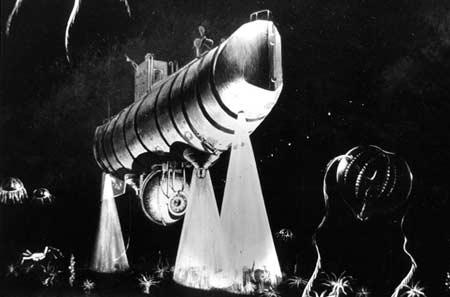

To withstand the high pressure at the bottom of Challenger Deep roughly eight tons per square inch the sphere's walls were 5 inches (12.7 cm) thick. To see outside, the crew relied on a window made of a single cone-shaped block of Plexiglas, the only transparent compound they could find strong enough to survive the pressure at the thickness needed, along with lamps to light up the sunless abyss.

"The pressure is tremendous," said geophysicist David Sandwell at the University of California, San Diego, who helped create the first detailed global maps of the seafloor.

The descent the first and only manned voyage to the bottom of Challenger Deep took 4 hours and 48 minutes at a rate of about a yard (0.9 meters) a second. As if to highlight the dangers of the dive, after passing about 27,000 feet (9,000 meters) one of the outer window panes cracked, violently shaking the entire vessel.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The two men spent just 20 minutes at the ocean floor, eating chocolate bars for energy in the cold deep, the temperature in the cabin was only 45 degrees Fahrenheit (7 degrees Celsius). They actually managed to speak with the craft's mothership using a sonar-hydrophone system at a speed of nearly a mile per second, it still took about seven seconds for a voice message to travel from the craft upward.

While at the bottom, the explorers not only saw jellyfish and shrimp-like creatures, but actually spied a couple of small white flatfish swimming away, proving that at least some vertebrate life could withstand the extremes of the bottom of the ocean. The floor of Challenger Deep seemed to be made of diatomaceous ooze a fine white silt made of microscopic algae known as diatoms.

To ascend, they magnetically released the ballast, a trip that took 3 hours, 15 minutes. Since then, no man has ever returned to Challenger Deep.

"It's hard to build something that can survive that kind of pressure and have people inside," Sandwell noted.

In many ways, the Trieste laid the foundation for the Navy's deep-submergence program. In fact, in 1963, it was used to locate the sunken nuclear submarine USS Thresher.

In addition, in recent years, robots have made the journey back to Challenger Deep. In 1995, the Japanese craft Kaiko reached the bottom, while the Nereus hybrid remotely operated vehicle reached the bottom last year.

Perhaps as explorers one day hope to return to the moon, so too might adventurers, and not just robots, revisit the deeps in the future.