Cute Cupid Is Year's Tiniest Valentine

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

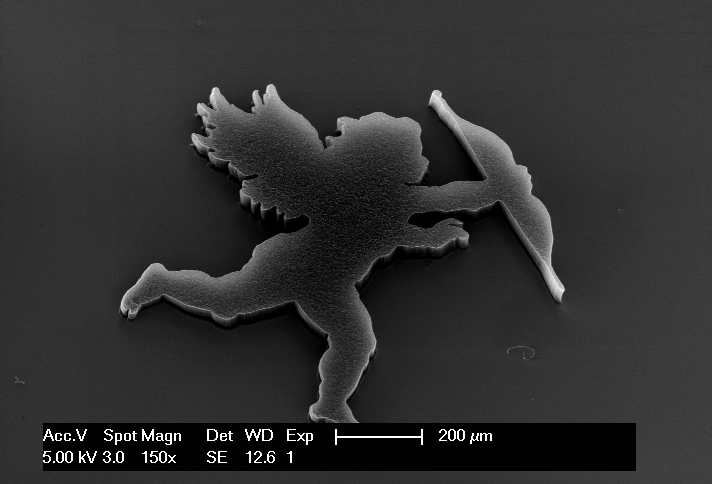

If this Cupid hit you with an arrow, you'd never feel it — its weapon is a mere fraction of the width of a human hair.

But this tiny Valentine is an example of big technology. Just a few hundred nanometers from foot to bow (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter), Cupid here is made from carbon nanotubules in a process that has been used in fields as diverse as mining and health care.

To make the tiny Cupid, physics students at Brigham Young University (BYU) first created the bow-wielding cherub shape with microscopic iron beads. They then blasted the beads with a puff of heated gas, which triggers the microscopic beads to transform into carbon nanotubules only 20 atoms across.

The resulting structure is as delicate as new love.

"Blowing on it or touching it would destroy it," BYU physics professor Robert Davis said in a statement.

Davis and his colleagues have ways to take the technology past the realm of fragile Valentines, however. Along with BYU physicist Richard Vanfleet, Davis has developed methods to strengthen the nanotube structures with metals and other materials.

One application is building itsy-bitsy nanofilters with great precision — these filters have holes about a tenth the circumference of a human hair, each perfectly spaced. Such nano-filters can be used in compressed gas systems in mining, health care and scuba diving, Davis said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus