Ancient Tapeworm Eggs Found in Fossilized Shark Poop

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient tapeworm eggs found in 270-million-year-old shark poop suggests these parasites may have plagued animals for much longer than previously known, researchers say.

Tapeworms cling to the inner walls of the intestines of vertebrates — creatures with backbones such as fish, pigs, cows and humans. When these parasites reach adulthood, they unleash their eggs on the world via the feces of their hosts.

Investigating the early history of such parasites of vertebrates is tricky because fossils of these parasites dating back to the age of dinosaurs or before are rare. One way researchers might unearth such fossils is by analyzing coprolites, or fossilized dung.

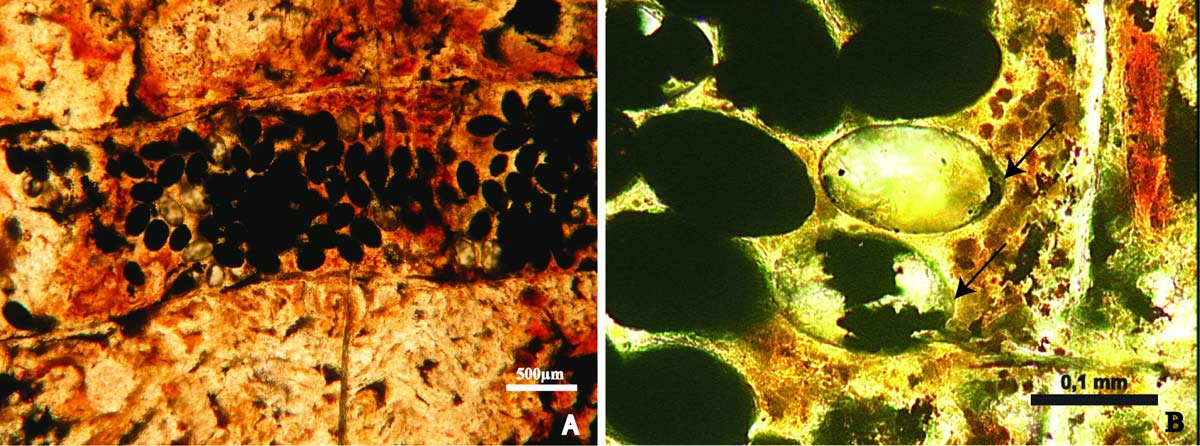

Scientists now reveal they found a spiral-shaped coprolite from a shark that holds a cluster of 93 oval tapeworm eggs. One of them even contains a probable developing larva, which held a cluster of fiberlike objects that may have been the beginnings of hooklets used to attach to a host's intestines as adults. [See Photos of the Parasite Eggs & Fossil Poop]

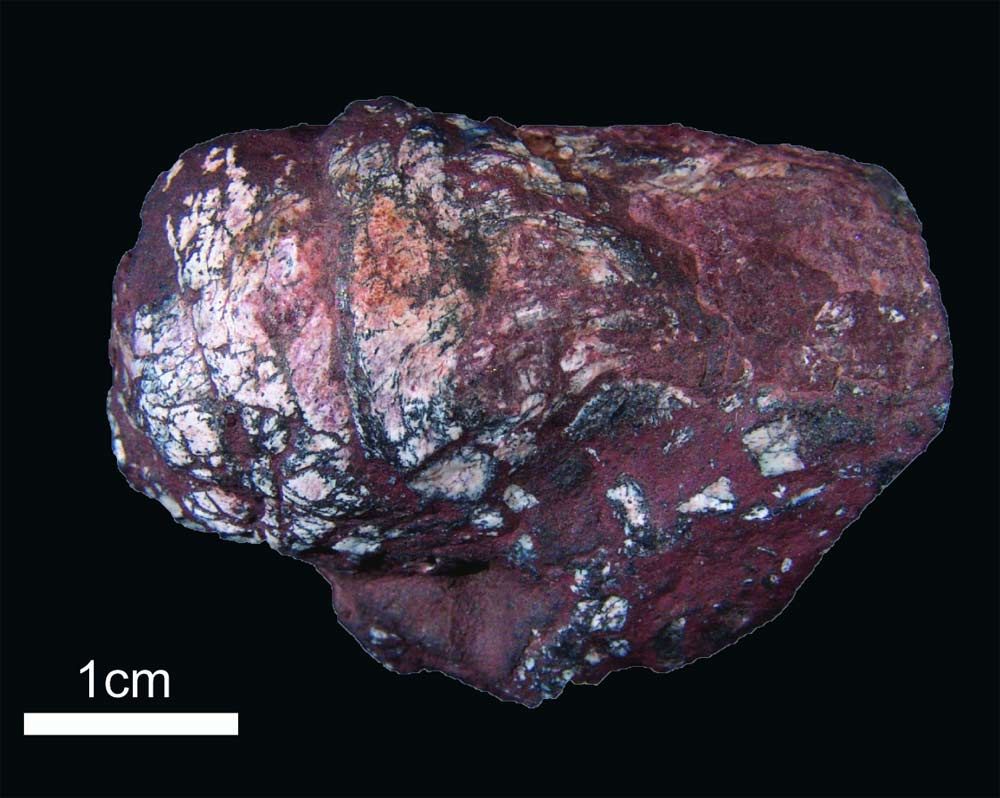

The fossils, unearthed in southern Brazil, date to the Paleozoic era (251 million to 542 million years ago), before dinosaurs roamed the Earth. This predates other known examples of intestinal parasites in vertebrates by 140 million years.

The eggs are each only about 150 microns long, or about one-and-a-half times the average width of a human hair. The researchers discovered the eggs by cutting coprolites into thin slices.

"Luckily in one of them, we found the eggs," researcher Paula Dentzien-Dias, a paleontologist at the Federal University of the Rio Grande in Brazil, told LiveScience. "The eggs were found in only one thin section."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This coprolite was found with more than 500 others at one site. The researchers suggest the area was once a freshwater pond where many fish got trapped together during a dry spell.

The mineral pyrite, also known as fool's gold, was found in the coprolite. This suggests its environment was depleted of oxygen, conditions that probably helped preserve the fossils for millions of years.

There is no way of knowing for certain what specific type of shark left this fossil behind, since all sharks have similar intestines (and thus poop). It is unlikely the tapeworm infestation killed the shark that left this coprolite, unless the infestation was huge, Dentzien-Dias said.

The researchers are now examining similar coprolites at the same outcrop. "We have to choose between 500 coprolites which ones will be cut," Dentzien-Dias said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 30 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus