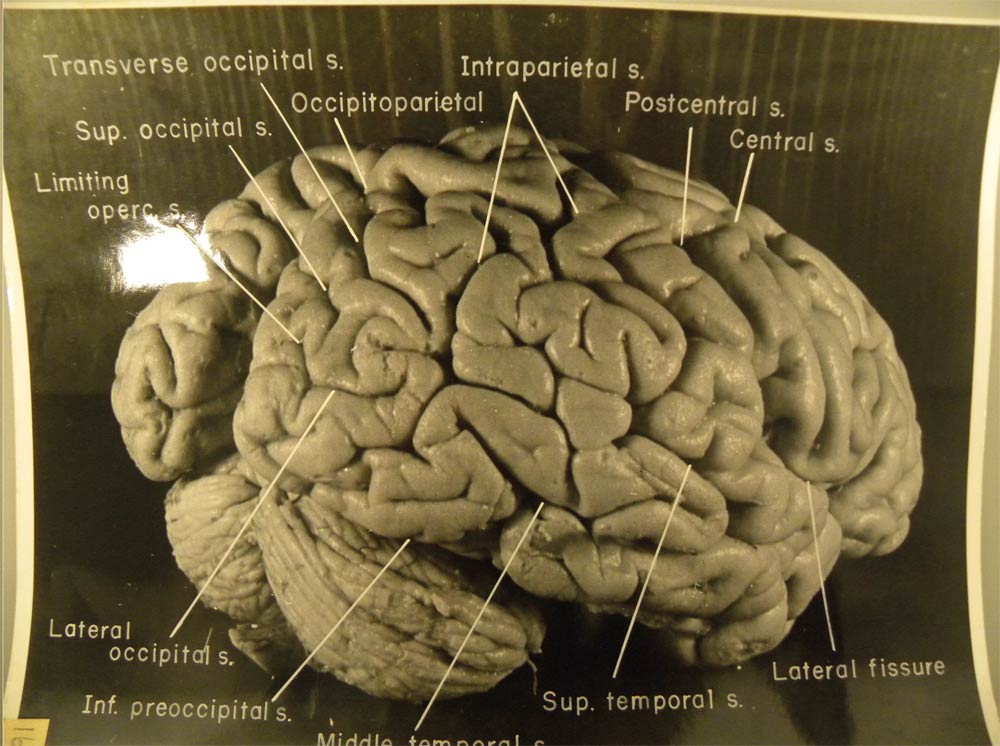

Einstein's brain had extraordinary folding patterns in several regions, which may help explain his genius, newly uncovered photographs suggest.

The photographs, published Nov. 16 in the journal Brain, reveal that the brilliant physicist had extra folding in his brain's gray matter, the site of conscious thinking. In particular, the frontal lobes, regions tied to abstract thought and planning, had unusually elaborate folding, analysis suggests.

"It's a really sophisticated part of the human brain," said Dean Falk, study co-author and an anthropologist at Florida State University, referring to gray matter. "And [Einstein's] is extraordinary."

Snapshots of a genius

Albert Einstein was the most famous physicist of the 20th century; his groundbreaking theory of general relativity explained how light curves due to the warping of space-time.

When the scientist died in 1955 at age 76, Thomas Harvey, the pathologist who autopsied him, took out Einstein's brain and kept it. Harvey sliced hundreds of thin sections of brain tissue to place on microscope slides and also snapped 14 photos of the brain from several angles.

Harvey presented some of the slides, but kept the photos secret in order to write a book about the physicist's brain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The pathologist died before finishing his book, however, and the photos remained hidden for decades. But in 2010, after striking up a friendship with one of the new study's co-authors, Harvey's family donated the photos to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. Falk's team began analyzing the photos in 2011. [See Photos of Einstein's Brain]

More brainy connections

The team found that, overall, Eintsein's brain had much more complicated folding across the cerebral cortex, which is the gray matter on the surface of the brain responsible for conscious thought. In general, thicker gray matter is tied to higher IQs.

Many scientists believe that more folds can create extra surface area for mental processing, allowing more connections between brain cells, Falk said. With more connections between distant parts of the brain, one would be able to make, in a sense, mental leaps, drawing upon these faraway brain cells to solve some cognitive problem.

The prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in abstract thought, making predictions and planning, also had an unusually elaborate folding pattern in Einstein's brain.

That may have helped the physicist develop the theory of relativity. "He did thought experiments where he'd imagine himself riding alongside a beam of light, and this is exactly the part of the brain one would expect to be very active" in such thought experiments, Falk told LiveScience.

In addition, Einstein's occipital lobes, which perform visual processing, showed extra folds and creases.

The right and left parietal lobes also looked very asymmetrical, Falk said. It's not clear how those features contributed to Einstein's genius, but that brain region is key for spatial tasks and mathematical reasoning, Falk said.

The jury is still out on whether Einstein's brain was extraordinary from birth or whether years of pondering physics made it special.

Falk believes both played a role.

"It was both nature and nurture," she said. "He was born with a very good brain, and he had the kinds of experiences that allowed him to develop the potential he had."

But most of Einstein's raw ability probably came from a trick of nature rather than a lifetime of hard work, said Sandra Witelson, a researcher at McMaster University who has done past studies of Einstein's brain. In 1999, her work revealed that Einstein's right parietal lobe had an extra fold, something that was either hardwired into his genes or happened while Einstein was still in the womb.

"It's not just that it's bigger or smaller, it's that the actual pattern is different," Witselson said. "His anatomy is unique compared to every other photograph or drawing of a human brain that has ever been recorded."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.