Earth's Clouds Alive With Bacteria

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

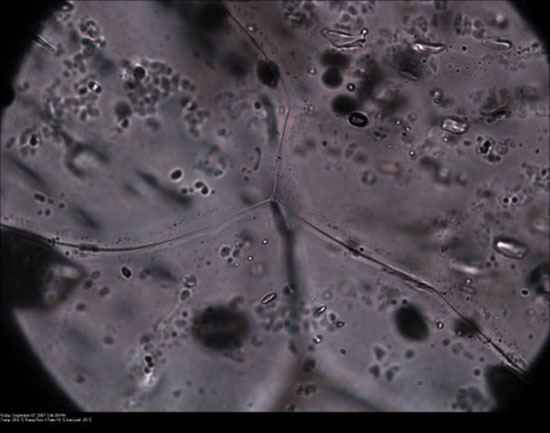

Clouds are alive with tiny bacteria that grab up water vapor in the atmosphere to make cloud droplets, especially at warmer temperatures, a new study shows. The water droplets and ice crystals that make up clouds don't usually form spontaneously in the atmosphere — they need a solid or liquid surface to collect on. Tiny particles of dust, soot and airplane exhaust — and even bacteria — are known to provide these surfaces, becoming what atmospheric scientists call cloud condensation nuclei (CCN). "Nucleation events and this ice formation is widely recognized as a process that is important to the initiation of precipitation, whether it be snowfall or rain," said lead author of the new study, Brent C. Christner of Louisiana State University. Biological nuceli Bacteria and other particles of biological origin are actually pretty good at collecting water vapor to form cloud droplets. "Biological particles such as bacteria are the most active ice nuclei in nature," Christner told LiveScience. "In other words, they have the ability to catalyze ice formation at temperatures warmer than a particle of abiotic origin." Whereas abiotic (or non-biological) particles such as dust are good at collecting water at temperatures below about 14 degrees F (-10 degrees C), biological particles seem to be the main active nuclei above that temperature, according to Christner's findings. This talent of bacteria could have implications for understanding cloud formation at warmer temperatures. Atmospheric bacteria To see how widespread biological nuclei were in the atmosphere, Christner and his team took samples of freshly fallen snow from sites all over the world. Antarctic snowfall had the lowest concentrations of biological nuclei, while sites in Montana and France had the highest. Christner said this finding was expected because Antarctica is isolated geographically and far from the suspected source of most of the biological nuclei, plants. "But the concentrations weren't zero; you could still measure some level of them," Christner said. "And that implies that these particles travel large distances in the atmosphere and retain their ice nucleating" properties. Most of the biological nuclei identified in the study, detailed in the Feb. 29 issue of the journal Science, were plant pathogens. These microbes could be carried into the atmosphere from an infected plant by winds, strong updrafts or the dust clouds that follow tractors harvesting a field. Christner and others suspect that becoming cloud nuclei is a strategy for the pathogen to get from plant to plant, since it can be carried for long distances in the atmosphere and come down with a cloud's rain. The next step in determining how big a role biological particles play in cloud droplet formation is to directly sample the clouds themselves, Christner says.

- The World's Weirdest Weather

- Weather 101: All About Wind and Rain

- Images: Curious Clouds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus