How Man-Made Jellyfish Could Help Heart Patients

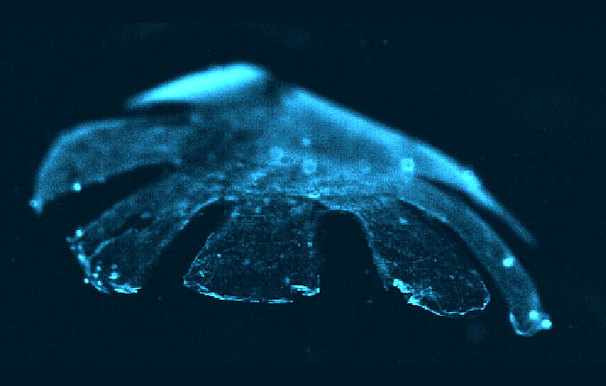

A half-inch-long juvenile jellyfish pulses and swims much like any of its compatriots in oceans all over the world. The major difference? It's entirely man-made. "It's a biohybrid robot. It's part animal, it's part synthetic material," said Kevin Kit Parker, a bioengineer at Harvard University who led the jellyfish-building effort.

The ultimate aim of Parker's little jellyfish isn't to build animals, however. It's to build artificial hearts for transplants in the future . Parker, who has long studied heart cells, chose to reproduce a jellyfish first, so he could learn the basics of biological pumps. "The jellyfish was a first step in that we built a functioning pump with designer specs," he told InnovationNewsDaily. "We're going to continue to try it to ratchet it up by building harder and harder things until we're ready for the heart."

His new artificial jellyfish is made from a combination of a thin, silicone material that's used in breast implants and heart cells harvested from unborn rats. Parker and his colleagues from Harvard and the California Institute of Technology analyzed a real jellyfish to learn exactly how the proteins in its body align with each other, then reproduced those alignments in the artificial design. A computer program the researchers wrote helped them quantitatively measure of how well the artificial design matched the natural one. [Jellyfish of War: Robojelly Holds Promise for Military Uses]

Along the way, they learned that that alignment is crucial for the jellyfish pumping motion to work correctly, Parker said. They also found that heart muscle protein and the jellyfish's muscle networks are similar to one another. "I don't think this is by accident. I think there's a way that nature builds muscular pumps," Parker said.

To get the jellyfish to move, researchers apply electricity to a tank of water with the human-made jelly inside. The rat heart cells in the jellyfish contract simultaneously in response to the electrical signal, just as jellyfish muscle cells do when the jelly pumps its body to swim.

The resulting motion looks much like the motion of a real jellyfish in its juvenile stage just before adulthood, Parker and his colleagues wrote in a paper they published today (July 22) in the journal Nature Biotechnology. The artificial jelly creates the same vortexes underneath the jellyfish's bell as the real deal does and otherwise moves the water around it in similar ways, they wrote.

Besides serving as a first template to making artificial octopuses, artificial stingrays and finally an artificial heart, Parker said he has patented his jellyfish as an artificial pump that drug companies can use to test heart medications that are still in their early stages of development.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even as he outlines all the uses an artificial jellyfish can have — as a way to learn about real, live, pumping hearts or as a testing ground for drugs — he seems just as excited about the coolness factor of building an animal many people find fascinating. "There's this great jellyfish thing over at the New England Aquarium and it really captures the imagination," he said. The New England Aquarium is just a few miles away from his lab at Harvard.

"Now that I've got a 3-year-old daughter, I'm trying hard to build things she will appreciate," he said.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus