Genetics by the Numbers: 10 Tantalizing Tales

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Genes: What's Your Number?

Scholars have been studying modern genetics since the mid-19th century, but even today they continue to make surprising discoveries about genes and inheritance. Here are some stats they’ve learned so far:

Learn more:

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

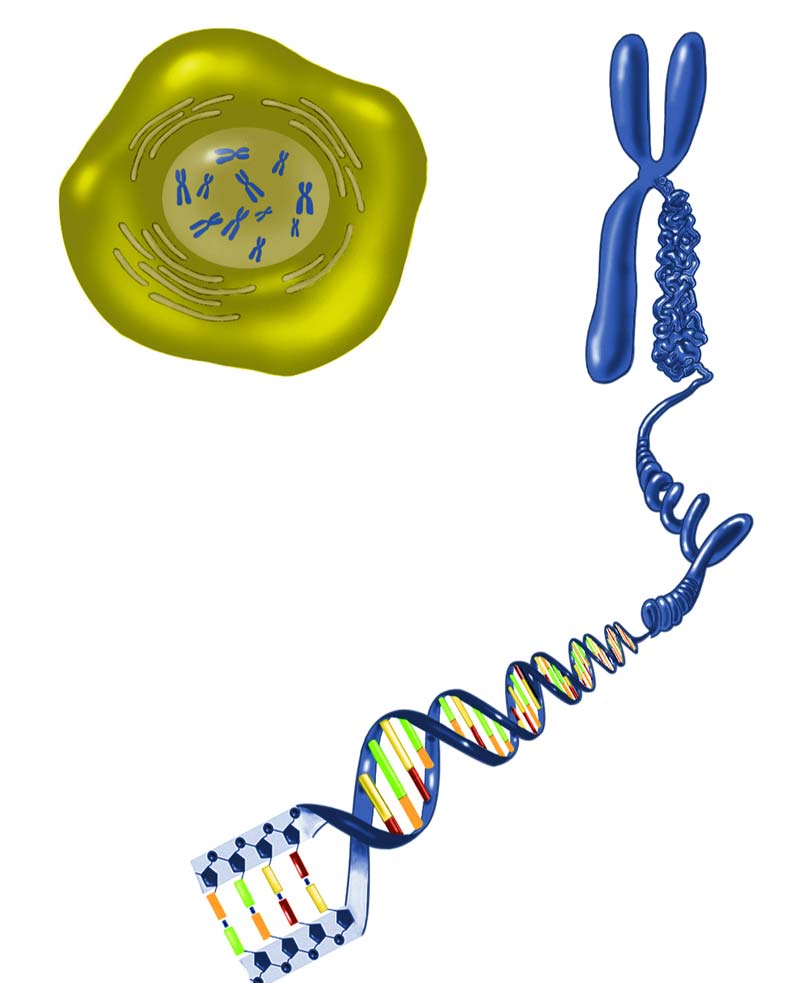

6

That's how many feet long the DNA from one of your cells would be if you uncoiled each strand and placed them end to end. Do this for all of your DNA, and the resulting strand would be 67 billion miles long — the same as about 150,000 round trips to the moon.

20,000

That's the approximate number of genes in the human genome. Our genes provide cells with information on how to make proteins. Scientists have estimated that humans may produce up to 100,000 proteins, so they thought there were about as many human genes. Today, they know that some genes contain the code for making multiple proteins.

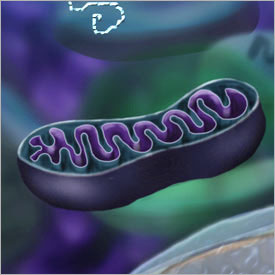

37

That's the number of genes in our "other" genome — the mitochondrial genome. Mitochondria are the cells' power plants, and many of their genes are involved in production of cellular energy. They have their own set of genes because they are thought to have evolved from bacteria that were engulfed by eukaryotic cells (cells containing a nucleus) some 1.5 billion years ago, during the Precambrian period.

3.2 Billion

That's how many base pairs — or sets of genetic "letters" — make up the human genome. In order to list all those letters, a person would have to type 60 words per minute, 8 hours a day, for about 50 years! However, humans are by no means the species with the most base pairs. The marbled lungfish (Protopterus aethiopicus) has about 133 billion of them in its genome.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

0.0002

That's the length in inches across a cell's nucleus, which holds your DNA. If you sliced human hair into tenths lengthwise, each slice would be about that big around. To keep the space tidy, DNA spools around a group of proteins called histones. The resulting taut package of wound-up DNA is called chromatin, which winds up even tighter to form your chromosomes.

99.6

The DNA of any two people on Earth is 99.6 percent identical. But 0.4 percent variation represents about 12 million base pairs, which can explain many of the differences between individuals, especially if the changes lie in key genes. Our environment also contributes to our individuality.

1/3

That's the fraction of human genes estimated to be regulated by microRNAs. These genetic "micromanagers" consist of only about 22 RNA units called nucleotides, but they can stop a gene from producing the protein it encodes. Scientists have identified hundreds of microRNAs in people and have linked disruptions in some of them to certain cancers.

98

More than 98 percent of our genome is noncoding DNA — DNA that doesn't contain information to make proteins. As it turns out, some of this "junk DNA" has other jobs. So far, scientists have learned that it can help organize the DNA within the nucleus and help turn on or off the genes that do code for proteins.

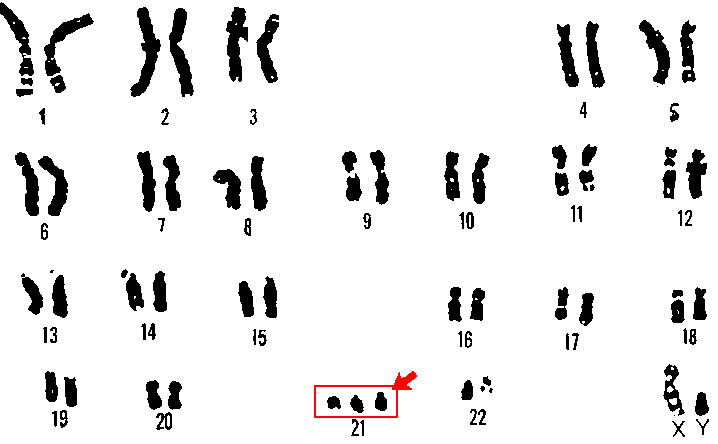

47

That's the number of chromosomes in the nuclei of a person with Down syndrome and certain other genetic conditions. Most human cells have 46 chromosomes, but occasionally, a glitch in cell division results in a cell with too few or too many chromosomes. When this happens in egg or sperm cells, the child can have an abnormal number of chromosomes. People with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21, one of the smallest chromosomes in the genome.

1953

That's the year when scientists uncovered the double-helical structure of DNA. Until then, scientists knew that traits were passed down to offspring in predictable ways, but they didn’t understand how. All that changed when James Watson and Francis Crick showed that DNA is shaped like a spiral staircase that can be split, copied and passed on to future generations. Watson and Crick received a Nobel Prize in 1962 for their discovery.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus