Greenland Glaciers Are Speeding Up

Greenland's ice sheet is on the move, with new images showing its glaciers moving 30 percent faster than they were a decade ago.

Greenland and Antarctica are home to the two biggest blocks of ice on Earth. As climate changes, these glacier are shrinking and the water contained in them is moving into the oceans, adding to the already rising sea level.

A glacier's velocity is a measure of how fast the ice on the surface of the sheet is flowing toward the edges of the sheet. This flow can be faster or slower, depending on how much the glacier is melting. The faster the flow, the more water and ice mass is lost from the glacier.

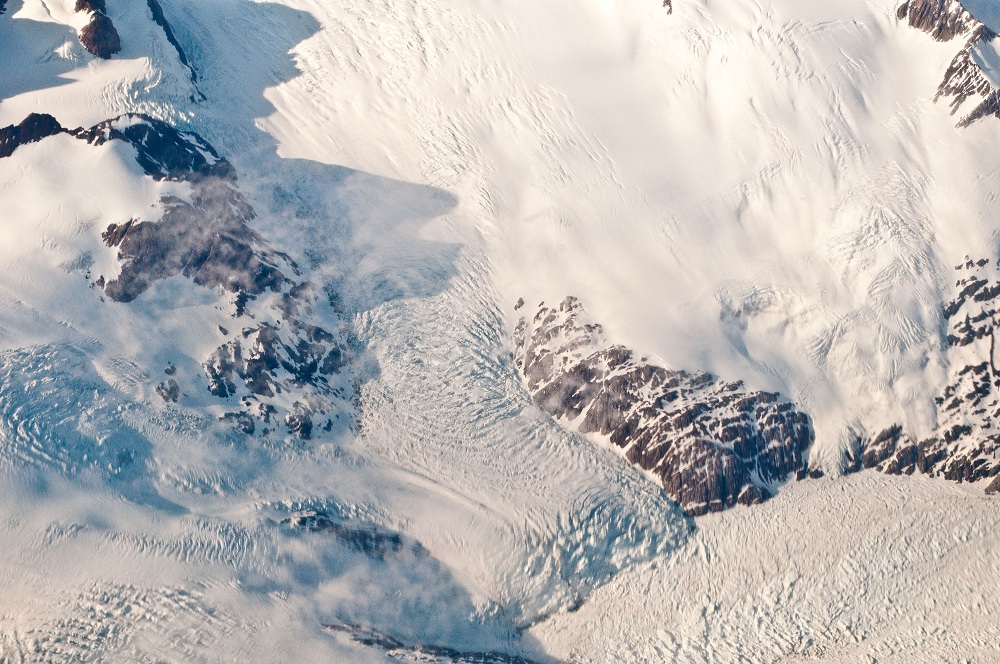

"You can think of the Greenland ice sheet as a really large lake that has hundreds of those little outlet streams that are acting like conveyor belts to move ice from the middle of the ice sheet, where it's getting added by precipitation, to the edges," study researcher Twila Moon, a graduate student at the University of Washington, told LiveScience. [Flowing Ice: Photos of Greenland Glaciers]

Great glaciers

The researchers analyzed satellite images of the Greenland glaciers taken between 2000 and 2010. These annual images were put through a computer program to detect how quickly the ice is moving. In general, the glacial flow has sped up by 30 percent over the 10 years, Moon said.

To get a better idea of the glacier's dynamics, the researchers looked at the area's more than 200 glaciers individually. Some of these glaciers end on land, some drop off into the sea, and the rest gradually extend their ice sheets into the water, creating an ice shelf.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers saw that the glacier's type has a big impact on how quickly it flows. Land-ending ice sheets can move 30 to 325 feet (9 to 99 meters) per year, while glaciers that terminate in ice shelves move much faster, from 1,000 to more than 5,000 feet (305 to 1,600 m) per year.

The glaciers that drop off into the sea are flowing the fastest, Moon said, up to 7 miles (11 kilometers) per year and their speeds are accelerating. "The areas where the ice sheet loses the most ice are also the areas we are seeing the biggest changes," Moon said.

Where and why

The ice flow depends on the glacier's location, and therefore the local climate. Most of the high-velocity glaciers are in the northwest and southeast of Greenland, and these are also the calving, ocean-ending glaciers. [Images of Greenland's Dramatic Landscape]

Greenland is "such a vast area that the systems of precipitation and temperature that we see in the north can be pretty different from other areas. It doesn't see the same kind of summer temperature changes," Moon said. "There are important local factors that are contributing to when and how much the glacier velocity changes."

There's no reason to think, from the new data, that the glaciers won't continue to gain speed. The result would be an increasing amount of ice and water adding to the sea level. Scientists see some good news: This average flow is actually slower than previous estimates suggested, meaning climate and sea-level rise models need to be tweaked.

"A lot of the drive behind current Greenland ice sheet and Antarctica studies is to ask, 'What sea-level rise can we expect?'" Moon said. "Both of these areas hold vast amounts of ice and the potential for very large sea-level rises. We need to understand what's happening on them to see what potential scenario will be realized."

The study is to be published tomorrow (May 4) in the journal Science.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.