How Tech Can Help Prevent Violence

Just as researchers are able to predict tornadoes and tsunamis, they can sometimes predict war and violence, too. Researchers developed the world's first early-warning systems to protect civilians after the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Now the Obama administration has put out a call for the next generation of technologies made to prevent mass torture, killings and more.

President Barack Obama announced the United States' new plans for responding to genocides worldwide on Monday (April 23). At the same time, USAID – a government agency responsible for providing humanitarian aid – issued a challenge seeking technology to prevent atrocities. The agency wants ideas from everybody, from established companies to students, Sarah Mendelson, an administrator in USAID's democracy, conflict and humanitarian assistance division, told InnovationNewsDaily. A panel of judges will make their first awards in January 2013.

How can gadgets and electronics systems save the world from another Holocaust or Rwandan genocide? InnovationNewsDaily spoke to a few experts to see what atrocity-preventing technology might look like.

Before: Predict and warn

Predictions and early warnings are key to diffusing a tense situation and getting people out of harm's way. The world already has warning systems set up, such as those run by the African Union and the United Nations, to predict and prevent violence. They usually predict events two to four weeks ahead of time and call together respected community leaders to try to de-escalate the violence. If leaders can't resolve their differences or they're dealing with forces beyond their control, people can leave the area, explained David Nyheim, a London-based consultant on international conflict.

There's room for improvement on today's warning networks, however, Nyheim said. The warning networks could incorporate more reports from people on the ground, using a system like Ushahidi, which allows people to send location-tagged text messages to a central server that plots the reports to a map. They could automatically gather information from publicly-available sources, such as newspaper reports and Twitter feeds, and then — the real challenge — turn that "firehose" of data into recommendations for what people should do. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation recently asked for similar technology to predict crimes and terrorist attacks.

Or they could do all of that at once. Nyheim pointed to one effort, called PAX, that hopes to combine crowd-sourced mapping, automatic Twitter and news-scraping and expert analysis into one global warning system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

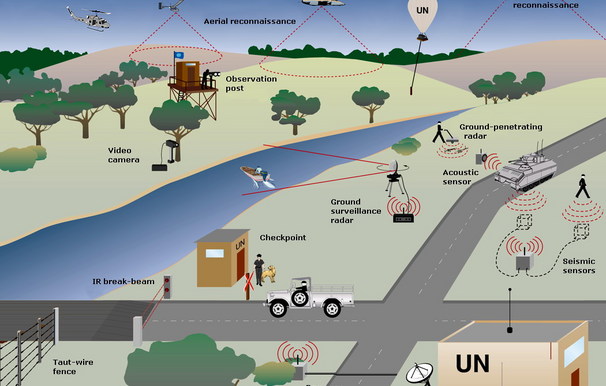

In a more expensive option, an improved early-warning system could also keep a literal eye on the ground. Balloons and manned and unmanned aerial vehicles can all keep watch on areas analysts know are likely to host violence, said Walter Dorn, a defense studies professor at the Royal Military College of Canada who has served as a consultant to the U.N.'s peacekeeping department. Militaries take spending for such technologies for granted. Peacekeeping operations deserve the same, he argues in a recent book, "Keeping Watch: Monitoring, Technology and Innovation in U.N. Peace Operations" (UNU Press, 2011).

Actor George Clooney recently received some media attention for funding satellites that monitor fighting at the border of Sudan and the newly-independent South Sudan. "We basically monitor all of the movement around the buildup to an attack," said Vincenzo Bollettino, executive director of the Harvard University institute that analyzes the Sudanese satellite images. Institute researchers issue periodic reports about what they see and attempt to get the word out through news agencies. Bollenttino told InnovationNewsDaily that with enough funding, the Sudan-monitoring effort could "absolutely" expand to other areas around the world.

At the other end of the spectrum, peacekeepers can increase the number of people who see their warnings simply by posting them on popular social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Dorn said. U.N. peacekeepers traditionally broadcast warnings over the radio and handed out flyers. They're now starting to post on social networks, he told InnovationNewsDaily.

Any warning system developers come up with should be able to work with cellphones, Nyheim said, because many people all over the world own them, even if they don't have access to other communication technologies. Even in developing countries, all cellphones can send text messages and many have Internet access, though most aren't as sophisticated as smartphones.

During and after: Gather evidence

If, in spite of all the warnings, an atrocity starts to happen, technology can record evidence that international courts can later use to bring people to justice.

Higher-resolution security cameras and cellphone cameras would help people document an atrocity as it happens, Dorn said. It would especially help if people could encrypt their pictures, send them to people outside of the country quickly and delete them from afar, in case their phones are seized. The distant-deleting function would help protect people from being punished for recording atrocities.

Cellphone cameras should have secure date, time and location stamps that will hold up in court, Dorn added.

Though cellphone providers' records are often used in U.S. court cases, many countries don't keep such records. Building systems everywhere that track who called whom, and when, would help prosecutors show who gave the orders for an atrocity. During an international court case on war crimes, "usually you have leaders at the top who are seeking some form of plausible deniability," Dorn explained. "'I didn't order it' or 'I wasn't in control of those troops.'" Call records are needed to undermine fraudulent deniability claims. "When you go for people at the top, you need to show that link."

Tech for better or worse

But the same technology that can protect civilians can help perpetuate violence. Those seeking to launch violence can use the same communication technologies to coordinate with each other and monitoring technologies to watch distant situations. "It's important to also understand, information is a tool for warfare," Nyheim said.

Violent militias can also intercept messages. If they see a civilian sending out reports, they may seek him out and harm him, Bollettino said. Technology developers will need to make sure messages in their systems are encrypted and rendered anonymous, he said.

Nyheim said a rise of atrocity-preventing technologies may spark a tech race between peacemakers and violence perpetuators, adding that peacemakers are "outgunned and out-resourced." Worldwide, the funds devoted to peacekeeping are a fraction of countries' and groups' war-making budgets, he said.

Yet he said that technology can help level the playing field, too. During last year's Arab Spring, for example, social media helped Arab protestors organize against much more powerful and better-funded existing regimes.

When it comes to a tech race in suppressing information versus spread it, USAID's Mendelson said, "Authoritarians are on the losing end."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily staff writer Francie Diep on Twitter @franciediep. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus