Small, Migrating Quakes Preceded Japan Megaquake

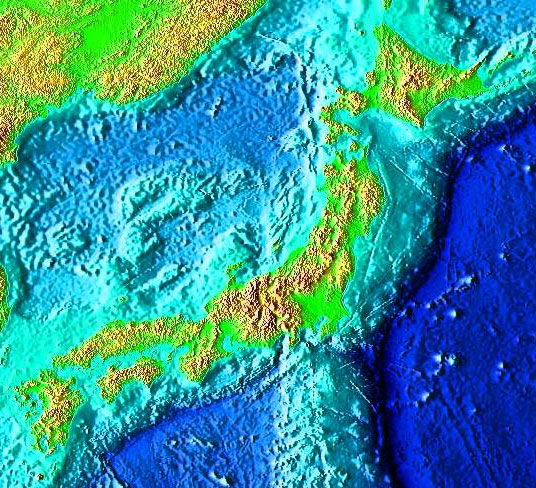

The devastating earthquake that struck Japan in early 2011 was apparently preceded by small, repeating quakes that migrated slowly to where the disaster eventually took place, scientists now find.

The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Oki temblor in March was the most powerful earthquake known to ever hit Japan and the fifth-most powerful quake ever recorded.

To find out more about why it happened — in the hopes of predicting any other such disaster — seismologists combed through records of seismic activity from before the rupture occurred. Their analysis identified small earthquakes that are normally obscured by overlapping seismic waves.

In the month before the Tohoku-Oki "megathrust" quake, the researchers found more than a thousand quakes migrated toward its hypocenter, the point where the quake's energy was released, at the rate of 1.2 to 62 miles (2 to 10 kilometers) per day. Their analysis suggests two sequences of faults slowly grinding against each other led to the initial rupture point of the disaster. The second of these sequences may have contributed enough stress to set off the main earthquake, they said.

"This finding may have a great potential to resolve the interactions between megathrust earthquakes and other phenomena," researcher Aitaro Kato, a seismologist at the University of Tokyo, told OurAmazingPlanet.

Kato noted they cannot yet predict if slow-slip events might lead to disasters. Whether or not major earthquakes occur likely depends on the level of stress built up in a fault and how much the slow-slip events add. To see how slow-slip events help trigger large quakes, "we would need to accumulate, through long-term monitoring of seismic and geodetic data, more observations showing the relationship between the propagation of slow-slip and the occurrence of large earthquakes," Kato said. "It is difficult to do definitive short-term prediction of mega-earthquakes at present, even though some slow-slip propagated."

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 19 in the journal Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus