Why Teens Are More Prone to Addiction, Mental Illness

By comparing the brain's response to a food reward in adult and teen rats, researchers have pinpointed some differences that might explain why adolescents take more risks and are more prone to addiction, depression and schizophrenia.

"The brain region that is very critical in planning your actions and in habit formation is directly tapped by reward in adolescents, which means the reward could have a stronger influence in their decision-making, in what they do next, as well as forming habits in adolescents," study researcher Bita Moghaddam, of the University of Pittsburgh, told LiveScience. "Teenagers could do stupid things in response to a situation not because they are stupid, but because their brains are working differently. Somehow they perceive and react to a situation differently."

The study was performed in rats, but teenagers throughout the animal kingdom show the same risk-taking and impulsive behaviors as human teens, so the results are likely to be applicable in humans too, the researchers said. Other studies show that the teen brain is also more susceptible to stress than the adult brain. Teenage brains are especially susceptible to addiction and mental illness, and the differences in the brain at that time may play a big role in these diseases.

"If your brain is processing the exact same thing differently, that could give us clues as to why their brain is more vulnerable," Moghaddam said. "By understanding what is happening in the brains of adolescents we can better understand how to prevent disease."

Teenage brain

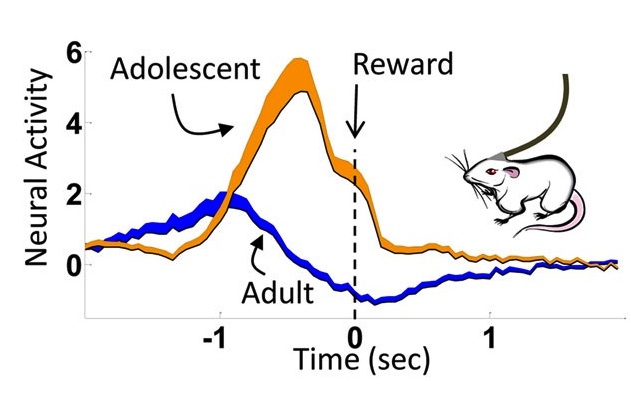

The researchers first taught the rats a basic trick: When presented with a tone, the rats learn that if they stuck their noses in a hole, they would get a food pellet. The researchers placed probes in each rat's brain to monitor the neurons in two brain regions — the nucleus accumbens and the dorsal striatum — while they performed this task.

The nucleus accumbens is the part of the brain that reacts with happy "reward" chemicals when we eat, have sex or do other things that ensure our survival. Drugs activate this region as well, creating an artificial reward signal by making these neurons send out their feel-good chemicals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers saw very similar reward responses in the nucleus accumbens when the rats received food pellets; the big difference between the brains of teenage and adult rats occurred in the dorsal striatum, where more activity showed up for teen rats about to get a food pellet. This brain region gets activated by the reward signals from the nucleus accumbens and is involved in habit formation, sort of sealing in the memory of "I put my nose in here and I get a treat that makes me feel good."

Disease state

These brain differences could manifest as the impulsive and risk-taking habits of your average teen.

"It could make the adolescent brain more vulnerable to what goes on around them in the environment, to things that are expected to be rewarding, and could make the brain more vulnerable to addiction," Moghaddam said. "Events or things in the environment could influence your next action more strongly in adolescents than in adults."

The researchers don't know how the brain changes from a teenage-like state to an adult state, but problems during this transition could lead to disease, the researchers said.

"Most of us turn into perfectly normal adults, but in some individuals this transition may not happen normally, it may under-correct or over-correct, and that's when disease could happen," Moghaddam said.

Leah Somerville, a researcher from Weill Cornell Medical College, who wasn't involved in the study, said it "offers an important advance to the understanding of how the [dorsal] striatum differentially represents motivated behavior in adolescents and adults. Ultimately, this work holds the potential to inform the mechanisms of adolescent risk-taking."

The study was published today (Jan. 16) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.