Tiny Ancient Swimmers Had Motion Detectors for Eyes

A tiny crustacean darted through the water after its next meal more than 500 million years ago. And, based on fossils of the animal, it probably was able to see the movement of this tasty morsel because of its sophisticated visual system.

This ancient animal's eyes would have been among the first stalked compound eyes in existence.

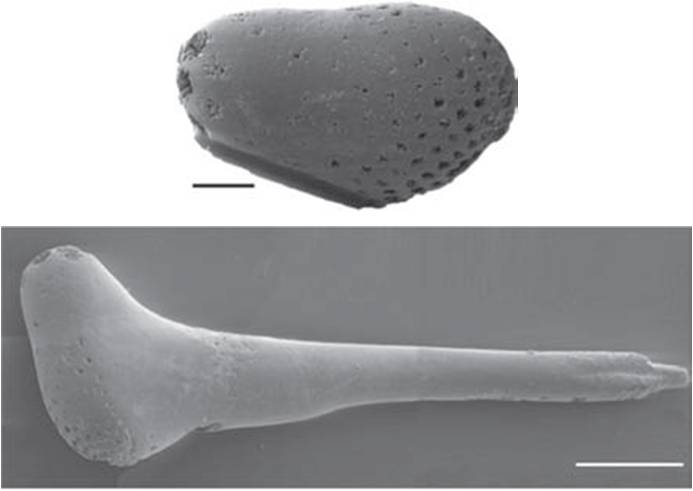

The exquisitely preserved fossils, discovered in Sweden in the 1970s, include six tiny stalked eye structures, each less than 0.01 inches (a third of a millimeter) long. The current research analyzed them using electron microscopy. Each individual eye facet can be made out on the tiny eye stalks, allowing researchers to analyze how the animal viewed and interpreted the world around it.

That, along with its body design, would've made for a powerful, albeit half-pint, predator. "They have certain appendages, and these appendages indicate that they would have eaten somebody else, and the eyes are specialized to support this," Study researcher Brigitte Schoenemann of the University of Bonn in Germany, said to LiveScience. "This specialization makes it possible even for such a small creature to live a predatory lifestyle."

Through crustacean eyes

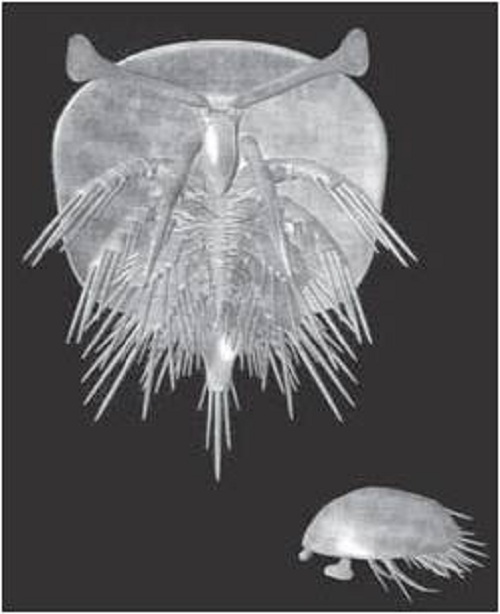

Henningsmoenicaris scutula was an early crustacean just a few millimeters long at most that lived in the surface layers of the water, where light was plentiful.

The creature would've sported compound eyes, much like those of a fly, but very different from human eyes. In compound eyes, each "eye," or facet, contains a specialized structure to detect a pixel of light. Each facet would send just one signal to the brain. By comparing the amount of light each pixel detects, the brain can make a shape or infer movement. If there are enough data points, an image starts to appear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specifically, H. Scutula had appositional compound eyes, something often seen in arthropods and crustaceans today. Such animals combine the signals from both eyes to form an image in the brain. H. Scutula's are the oldest confirmed appositional eyes that researchers have found. (Older compound eyes have been found, but the fossils aren't complete enough to determine to this extent how the animals carrying them saw.)

Crustacean coordinates

The eyes have a very large range of view, with different parts of the eyes equipped with particularly sized and spaced facets. The stalks, which allowed the eye structures to rest above the animal's body, were probably also moveable, so the crustacean would have had an even larger range of view.

It could see below into the dark depths of the ocean with facetsfacing downward that were larger and more sensitive to light, the researchers suspect. "The back of this eye looks to the ground, where it is dark; it has large lenses where it can catch a lot of light so it can look down into the dark," Schoenemann said.

Though the crustacean's eyes were tiny, had only a small number of facets and couldn’t make out actual images, its visual system was actually quite complex. The eye stalks had specialized sensors that faced inward, toward the space between the two stalks. The areas covered by these sensors would have overlapped, giving a better picture of movement around the animal.

"They developed another 'idea,'" Schoenemann said. "If there is an 'invader' into the visual field from one side of the animal, it is visually captured by one facet of the left eye and one of the right immediately, so there are coordinates like in a chess game."

The study was published today (Nov. 1) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Academy B: Biological Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus