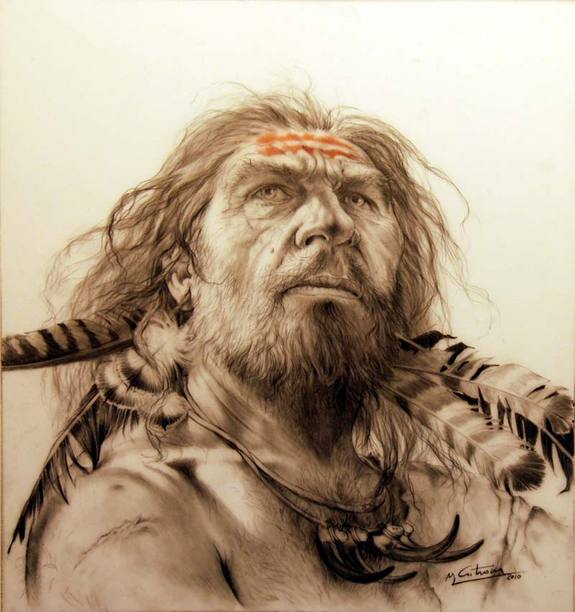

Masses of Humans May Have Sent Neanderthals Packing

Territory wars, superior brain power, better tools, changing climate — many reasons have been suggested as to how humans won out over Neanderthals in Europe, but new research is suggesting that pure population power may have been the key.

"All kinds of theories have been put forward in the past, but what we've wanted to do, is to make some kind of estimate of the relative numbers of late Neanderthals compared to modern humans," study researcher Paul Mellars, of Cambridge University in the United Kingdom, told LiveScience. "We suspected modern humans came in much greater population numbers, the Neanderthals were just swamped by much larger numbers."

From examining the sites inhabited by humans and Neanderthals in what is now southern France, Mellars found that humans eventually outnumbered the Neanderthals by about 10 to one. "Nobody has ever analyzed the data, this is the first time it's been analyzed," Mellars said. "It staggered me when I discovered the scale of the contrast."

While researchers not involved in the study think the idea is credible, they point out that population increases may not have been the only factor involved in the Neanderthals' demise; in addition, the study only provides evidence for the die-out in France, leaving the question of how other Neanderthals were wiped out open.

Out of Africa

Modern humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago. About 10,000 to 15,000 years later they reached the home range of the closely related species, the Neanderthal, who had been living in Europe for more than 200,000 years. A large portion of their population inhabited the valleys of what is today southern France.

Mellers and his team analyzed the settlements in these areas, spanning about 30,000 square miles (75,000 square kilometers). The settlements dated back between 35,000 and 55,000 years ago. About half of the period was before humans arrived, the other half after, during the decline of the Neanderthals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They determined which settlements were made by humans and which by Neanderthals by looking at the types of tools found at the sites. Then, to estimate population, the team analyzed the number of sites occupied by each species, how large each of the sites was, and the number of tools at each.

Population pressure

They determined that each of the three factors (size of site, number of sites and number of tools) indicated a two to threefold increase in the number of humans in the area. Taken together, the three factors suggested human numbers were nine to 10 times that of Neanderthal numbers. Mellars believes that this could have been the main factor that pushed the Neanderthals out of France.

"When you multiply them all together it suggests that the modern humans were living in at least 10 times the population density [of the Neanderthals]. The poor final Neanderthals there were conquered by these others coming over the hill in 10 times' greater numbers," Mellars said. "You could go away, go somewhere else and go into the hills. They were overwhelmed by the numbers."

Francesco d'Errico, a researcher at the University of Bordeaux in France who wasn't involved in the study, questions Mellars' approach, and thinks that both increasing human populations and climate change could have been a factor in the demise of the Neanderthals.

"Calculating [the] number of people from archaeological evidence is a risky endeavour, particularly for this time period, and each of the parameters used in this study, including chronology, could be called into question," d'Errico told LiveScience in an email. "Other equally acceptable parameters may have produced a different or at least much less contrasted picture."

Ludovic Slimak, a researcher at the University of Toulouse in France who wasn't involved in the study, pointed out to LiveScience that while a human population explosion may have played a role in this area, there is no proof that it led to Neanderthals' demise in other areas, even in other areas of France.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus