Monster Black Holes Aren't Always Born in Galaxy Collisions

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A collision between galaxies was thought to create a feast of matter to be eaten by the huge black holes lurking in their centers. But new research indicates such galaxy crashes aren't responsible for the outbursts caused by gorging black holes.

Instead, mysterious forces within the galaxies might be to blame.

At the heart of virtually all large galaxies are supermassive black holes million to billions of times the mass of the sun. In many galaxies, including our Milky Way, the central black hole is quiet, but in others known as active galaxies, matter at the nucleus of the galaxy gives off intense radiation as it gets sucked into the core black hole.

Scientists had thought most active galactic nuclei were triggered by two galaxies merging or passing close to each other. Such titanic disturbances could drive material from a galaxy's disk toward its core. But now researchers find these monumental disruptions are often not to blame for activating the black holes.

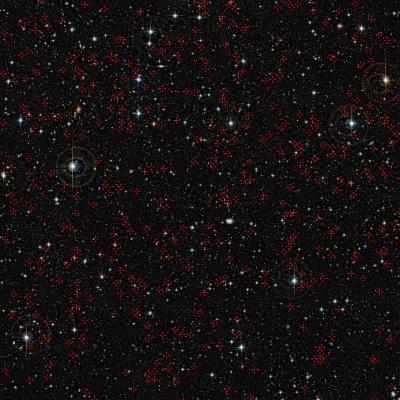

An international team of scientists working on the COSMOS (Cosmological Evolution Survey) experiment investigated more than 600 active galaxies using the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton space observatory and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile. Their observations allowed them to make a three-dimensional map showing the locations of the active galaxies. Because light takes time to travel, knowing the distance of these galaxies from Earth also helped reveal their ages. [Gallery: Black Holes of the Universe]

"It took more than five years, but we were able to provide one of the largest and most complete inventories of active galaxies in the X-ray sky," said researcher Marcella Brusa at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics at Garching, Germany.

The scientists calculated that the brightest active galaxies were most common in the universe about three billion to four billion years after the Big Bang, while the less brilliant nuclei appeared later, peaking at approximately eight billion years after the Big Bang. (The universe is now about 13.7 billion years old.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although a few of the active galaxies were extremely brilliant, most of them were only moderately bright. Surprisingly, the researchers found that galactic collisions were not responsible for activating most of the more common, moderately bright active galactic nuclei.

If active nuclei were the consequences of colliding galaxies, as had been expected, scientists would have found them in galaxies with only moderate masses — those about a trillion times the mass of the sun. Instead, the researchers found that most active nuclei reside in galaxies with masses about 20 times larger than the collision theory had predicted — galaxies that contain lots of the invisible, as-yet-unidentified dark matter that makes up about 85 percent of all matter in the universe.

Even in the distant past, up to almost 11 billion years ago, when the universe was only about 2.7 billion years old, "galaxy collisions can only account for a small percentage of the moderately bright active galaxies," said researcher Alexis Finoguenov at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. "At that time galaxies were closer together so mergers were expected to be more frequent than in the more recent past, so the new results are all the more surprising."

"These new results give us a new insight into how supermassive black holes start their meals," said researcher Viola Allevato at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics at Garching, Germany. "They indicate that black holes are usually fed by processes within the galaxy itself."

For instance, molecular clouds in a massive galaxy's disk might get driven into its central black hole by perturbations in the disk, Finoguenov told SPACE.com.

The scientists will detail their findings in the Astrophysical Journal this month.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus