8 New Substances Added to List of Carcinogens

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

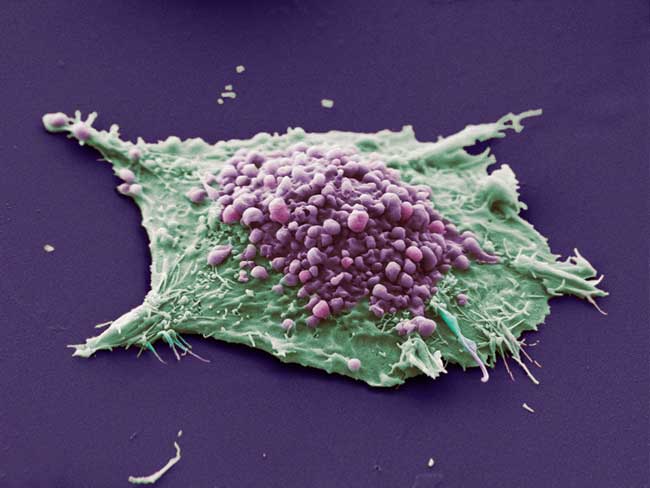

Eight new substances have been added to a list of carcinogens by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The congressionally mandated report identifies substances that are either known to be human carcinogens or are reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen. The new additions, announced on June 6, include formaldehyde and aristolochic acids, a family of acids that occur naturally in some plant species, which are now both considered known human carcinogens.

In addition to being used in medical laboratories and mortuaries as a preservative, formaldehyde is widely used to make resins for household items such as composite wood products, paper product coatings, plastics, synthetic fibers and textile finishes.

The six other additions, all of which fall into the second "anticipated" category, include:

- Captafol: a fungicide that had been used to control fungal diseases in fruits, vegetables, ornamental plants, and grasses, and as a seed treatment. It has been banned in the United States since 1999, but past exposures may still have an effect on health.

- Cobalt-tungsten carbide (in powder or hard metal form): commonly referred to in the United States as cemented or sintered carbide, this substance is used to make cutting and grinding tools, and wear-resistant products for various industries, including oil and gas drilling, as well as mining.

- Certain inhalable glass wool fibers: include only those fibers that can enter the respiratory tract, are highly durable, and are biopersistent, meaning they remain in the lungs for long periods of time. The largest use of general purpose glass wool is for home and building insulation, which appears to be less durable and less biopersistent, and so less likely to cause cancer in humans.

- o-nitrotoluene: used as an intermediate in the preparation of azo dyes and other dyes, including magenta and various sulfur dyes for cotton, wool, silk, leather and paper; it is also used in preparing agricultural chemicals, rubber chemicals, pesticides, petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals and explosives.

- Riddelliine: found in certain plants of the genus Senecio, a member of the daisy family, grown in sandy areas in the western United States and other parts of the world. Though not used commercially in the United States, many species have been identified in herbal medicines and teas.

- Styrene: a synthetic chemical used worldwide in the manufacture of products such as rubber, plastic, insulation, fiberglass, pipes, automobile parts, food containers and carpet backing. People may be exposed to it by breathing indoor air with styrene vapors from building materials, tobacco smoke and other products. The greatest exposure to styrene in the general population is through cigarette smoking.

"Reducing exposure to cancer-causing agents is something we all want, and the Report on Carcinogens provides important information on substances that pose a cancer risk," Linda Birnbaum, director of both the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program, said in a statement.

With these additions, the 12th Report on Carcinogens now includes 240 listings, which can all be found here. Each substance undergoes an extensive evaluation with numerous opportunities for scientific and public input before it is added to the report.

However, even if a substance is listed in the report, it doesn't necessarily mean that it will cause cancer. Many factors influence whether a person will develop cancer, including an individual's susceptibility to a particular substance, and the amount and duration of exposure to the substance.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus