Arizona Wildfire Blamed on 'Too Many Trees'

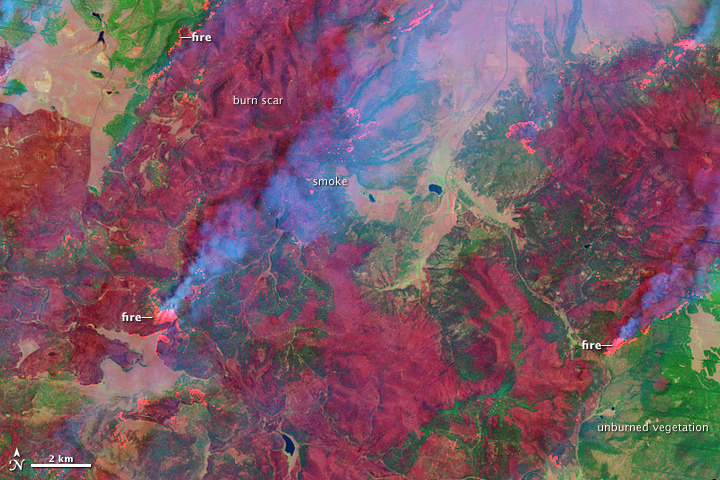

The Wallow Fire in eastern Arizona is now the second-largest fire in Arizona history, engulfing nearly 400,000 acres in flames. Some forest experts warn that an overly dense, unnatural forest structure is fueling the fire and putting millions more acres of trees at risk.

"Decades of scientific research reveal that the West is suffocating under too many trees," Wally Covington, a professor of forest ecology at Northern Arizona University and executive director of NAU's Ecological Restoration Institute, said in a statement. "Where we once had 10 to 25 trees per acre, we now have hundreds."

For years, forest researchers have warned that millions of small-diameter trees pose a threat to the nation's forests. Too many trees on the forest floor set the perfect conditions for a catastrophic wildfire, with the smaller trees serving as a source of fuel to feed the fire, according to Covington.

The eastern Arizona forest, which mostly consists of ponderosa pine, used to have natural fires that burned along the forest floor every two to 10 years, killing excess tree seedlings, recycling nutrients and removing dead and dying trees in the process. Now, because of the dense overgrowth of small-diameter trees, the fires are climbing and spreading to the high treetops. [Read: Arizona Wildfire Sparks Racist Rumors]

Covington warns that about 180 million acres (73 million hectares) of ponderosa pine across the West are at risk due to overgrown trees. Collaborative efforts such as the Four Forest Initiative aim to increase large-scale forest restorations, which thin out trees so that forests do not become wildfire liabilities.

"Especially with drought and climate change, there is an urgent need to restore forests to their most resilient condition," Covington said. "That requires protecting the old-growth trees and thinning most of the small-diameter trees."

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescienceand on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus