Exclusive: Early Christian Lead Codices Now Called Fakes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Seventy metal books allegedly discovered in a cave in Jordan have been hailed as the earliest Christian documents. Dating them to mere decades after Jesus' death, scholars have called the "lead codices" the most important discovery in archaeological history, and leading media outlets have added fuel to the fire surrounding the books in recent weeks.

"Never has there been a discovery of relics on this scale from the early Christian movement, in its homeland and so early in its history," reported the BBC. [Image]

Slowly, though, more and more questions have arisen about the authenticity of the codices, whose credit-card-size pages are cast in lead and bound together by lead rings. Today, an Aramaic translator has completed his analysis of the artifacts, and has found what he says is incontrovertible evidence that they are fakes.

Mixed messages

"I obtained photos of all the text that was available, and spent the past week looking over them," said Steve Caruso, a professional Aramaic translator and teacher who is consulted by dealers of antiquities to analyze inscriptions on ancient artifacts.

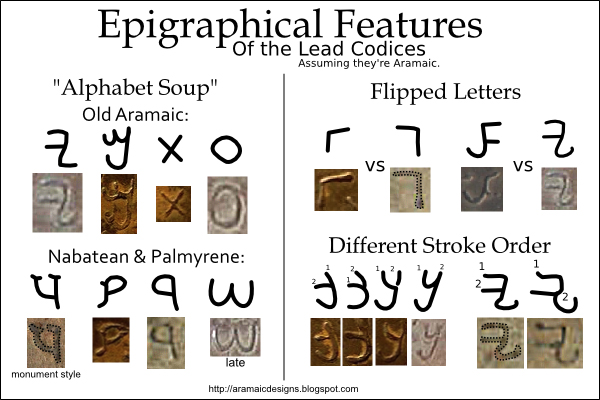

"I noticed there were a lot of Old Aramaic forms that were at least 2,500 years old. But they were mixed in with other forms that were younger, so I took a closer look at that and pulled out all the distinct forms that I could find," Caruso told Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. "It was very, very odd — I've never seen this kind of mix before." The youngest scripts he identified, called Nabatean and Palmyrene, date from the second and third centuries, proving the documents could not possibly have been written during the dawn of Christianity, Caruso said.

Even the oldest scripts were written by someone who didn't know what he was doing, the new analysis shows. "There were inconsistencies in how they did the stroke order, which you would never have seen. Scribes had very specific ways of doing things," Caruso said. Furthermore, several characters appeared "flipped" — a mistake that would imply they were hastily copied rather than original.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Caruso's new analysis of the text corroborates the recent findings of a Greek archaeologist at Oxford, who said the images appearing in the codices, including one of Christ on the cross, are anachronistic. "The image they are saying is Christ is the sun god Helios from a coin that came from the island of Rhodes. There are also some nonsense inscriptions in Hebrew and Greek," Peter Thonemann told the press. He believes the codices were forged within the past 50 years.

One scholar who continues to believe in the authenticity of the codices is David Elkington, described by the BBC as a scholar of ancient religious archaeology. For months, Elkington has been trying to help the Jordanian government retrieve the codices from Israel, where they were smuggled.

Elkington and his team have argued that the codices show images of Jesus with God, as well as a map of Jerusalem, and text discussing the coming of the Messiah. Furthermore, they say the books were found near where early Christian refugees are thought to have camped.

The team even identified a fragment of text reading "I shall walk uprightly," a possible reference to Jesus' resurrection.

However, Elkington's credentials may not have been questioned thoroughly enough by the media outlets that gave him a platform. "The 'British archaeologist' who is named as apparently trying to get these things into a Jordanian museum and who is one of the few who has actually seen them, one David Elkington, is not an archaeologist," said Kimberley Bowes, a Greek and Roman archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

"He doesn't seem to occupy any post or other academic position, and his writings on how acoustic resonance is responsible for major world religions wouldn't be accepted by any academic or scholar I know," Bowes told Life's Little Mysteries.

Just in time for Easter

"I was a little bit surprised that they did take on as much media coverage as they did," Caruso said. "The media took the press release hook, line and sinker without doing serious investigation. If they had they would have found that David Elkington, who brought them to the forefront, is in the fringe of academia."

Some good photos and good timing probably gave the artifacts a boost. "I think there were a lot of really, really good photos, and the whole thing seemed convincing on the surface. People are looking for something to write about in the Easter season and this is something that would make great news."

Fake Christian relics are relatively common, Bowes said. "Modern people's urge to find material evidence from the first two centuries of Christianity is much stronger than the actual evidence itself. This is because the numbers of Christians from this period was incredibly small — probably less than 7,000 by 100 A.D. — and because they didn't distinguish themselves materially from their Jewish brethren."

Caruso is regularly asked to analyze antiquities. "I've actually found a lot more gibberish or fakes than actual artifacts, which is the sad part," he said.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus