Scientists created the whitest paint ever

The white color reflects so much light that it cools surfaces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

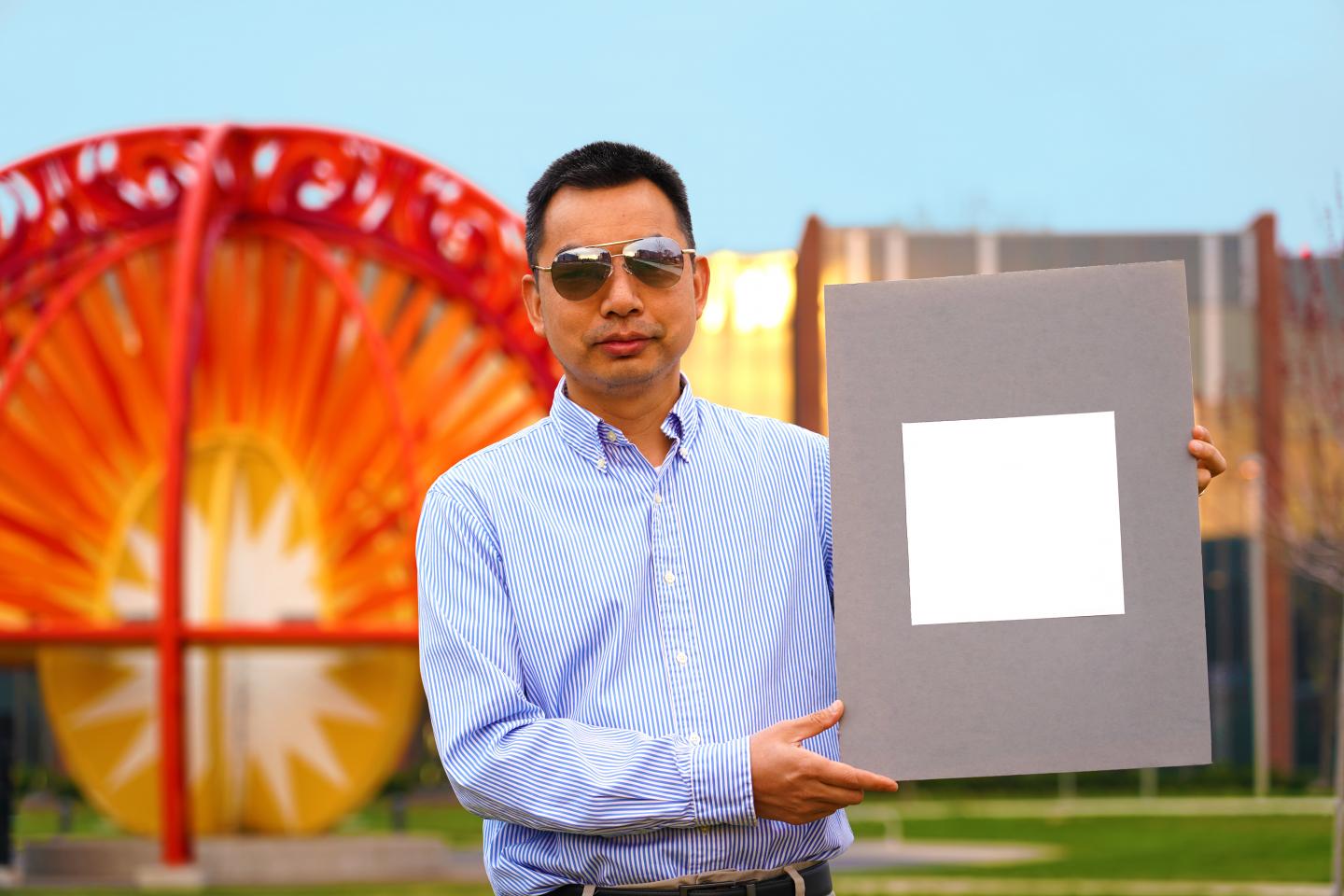

Engineers have created the whitest paint ever, and they think it can help fight a warming planet.

This whitest paint surpasses the ultrawhite paint that the same group of engineers at Purdue University revealed in October 2020, and it can cool buildings just as an air conditioner would, they report in a new study.

If the paint were to cover a roof 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) in area, it would have a cooling power of about 10 kilowatts. "That's more powerful than the central air conditioners used by most houses," senior author Xiulin Ruan, a mechanical engineering professor at Purdue University in Indiana, said in a statement.

Related: Top 10 craziest solutions to global warming

The paint's cooling power comes from its impressive ability to reflect sunlight — and thus infrared heat. Commercially available paints that are specifically designed to "cool," reflect about 80% to 90% of sunlight, but they can't cool surfaces to temperatures that are lower than their surroundings, according to the statement.

The new ultrawhite paint, by contrast, reflects 98.1% of sunlight — much more than the former record holder, which reflected 95.5%. The paint is the opposite of the ultrablack one researchers created in 2014, called "vantablack," which absorbs 99.9% of visible light.

To create the new paint, the team considered more than 100 white materials and then tested about 10 of them in different formulations. Their previous ultrawhite paint was made of calcium carbonate, a compound found in rocks and seashells, according to the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The engineers made the new paint using high concentrations of barium sulfate, a white, odorless insoluble compound that's used as a "contrast media" in X-rays or CT scans by coating the walls of the esophagus, stomach or intestine so that they can be imaged clearly. It's also used to make photo paper and cosmetics white.

The engineers further increased the white paint's reflectivity by varying the particle sizes of barium sulfate. How much light each particle scatters depends on its size; the range of sizes allows the paint to scatter many different wavelengths, according to the statement.

The group found that their paint can keep surfaces about 19 degrees Fahrenheit (10.6 degrees Celsius) cooler than ambient surroundings at night and 8 F (4.4 C) cooler than their surroundings while the sun is strong, around noon.

But the paint also cooled temperatures during wintertime. When the outside temperature was 43 F (6 C), the paint decreased the sample temperature by 18 F (10 C). The researchers have now filed a patent application for this extremely white — and cool — paint. They are also working with a company to make and sell the paint, according to the BBC.

Certain cities are already painting roofs white to save energy. New York, for example, has recently painted 10 million square feet (929,000 square m) of rooftops white, according to the BBC. Scientists are also considering the possibility of using the paint to cool down the planet if it were to coat areas where people didn't live.

"We did a very rough calculation," Ruan told the BBC. "And we estimate we would only need to paint 1% of the Earth's surface with this paint — perhaps an area where no people live that is covered in rocks — and that could help fight the climate change trend."

Still, others were cautious about the findings. The paint is only a small improvement over commercially available paints, Ronnen Levinson, the leader of the Heat Island Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory told The Washington Post. "Cooling benefits are usually evaluated after a reflective material has been outside for a few years," he told the Post. "I don’t really know how the ultrabright white will perform then. But from its initial properties, when it’s clean, it’s about a 10 percent performance boost over today’s bright-white roof coatings."

The findings were published April 15 in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus