Honeybee 'Trojan horse' virus relies on bees' habit of cannibalizing their young

An increasingly virulent pathogen is turning hygienic cannibalism on its head.

A virus that leaves bees with stubby, useless wings, bloated abdomens and sluggish brains before killing them off takes advantage of one of the pollinators' nastier habits — a tendency to cannibalize their young, a new study found.

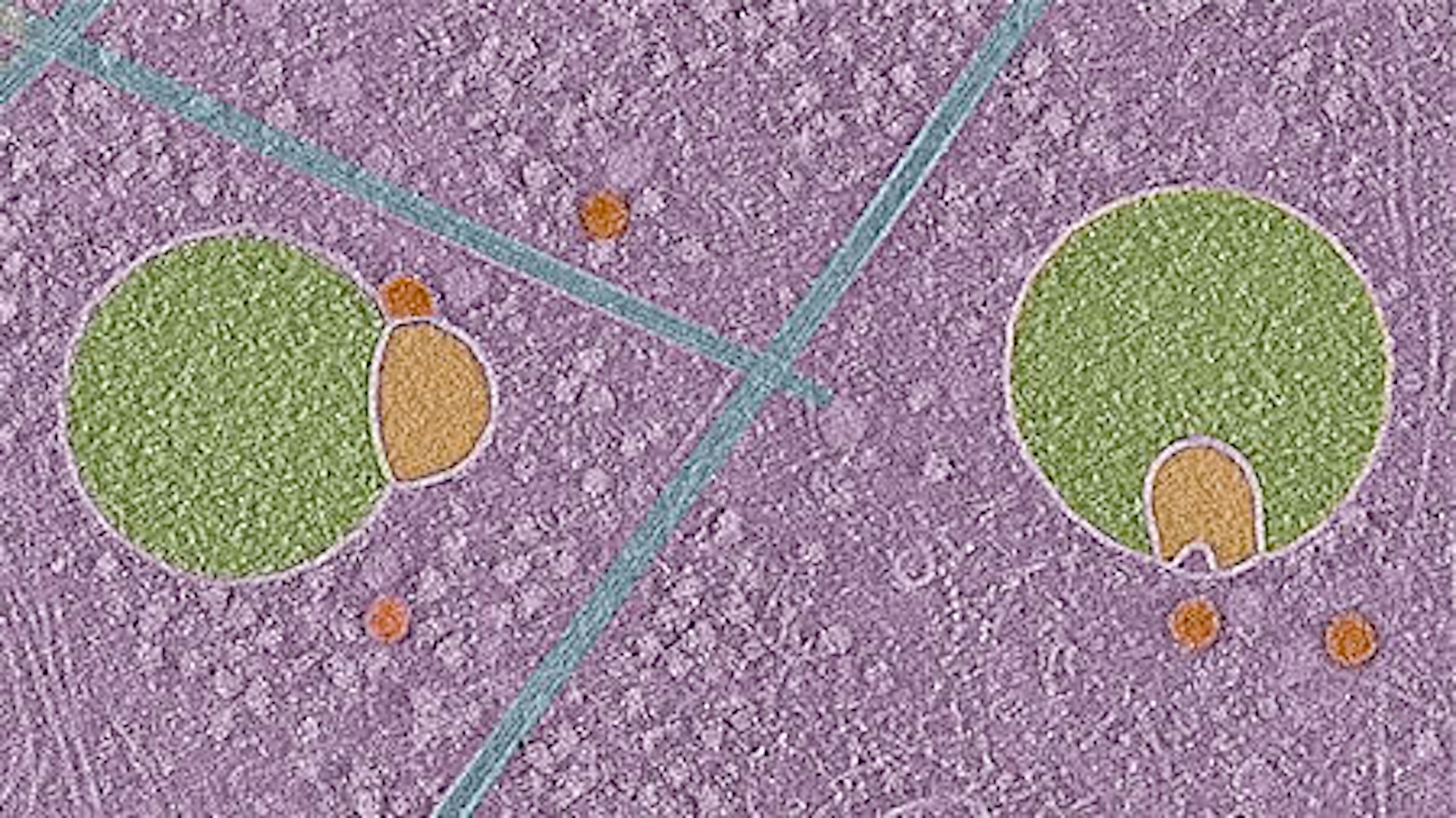

The deformed wing virus (DWV) lurks inside the bellies of mites that prey on the bees' young; then, the worker insects get infected when they gobble up the baby bees, the study researchers found.

This finding may explain why DWV has become much more catastrophic, often leading to colony collapse, now compared with in the past. Research published April 26 in the journal Scientific Reports has found that the increasing virulence of DWV is due, in part, to the honeybee's cannibalism behaviors.

Related: Gorgeous images of Australia’s ‘rainbow’ bees will blow your mind

When a larval honeybee (Apis mellifera) is sick, a worker bee is likely to sniff out the infection, open the cap on the sick larva's brood cell and eat it. Entomologists call this behavior hygienic cannibalism.

"It's a beneficial behavior, and many beekeepers actively breed for it," said Jay Evans, an entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Bee Research Laboratory. It's especially useful for fighting bacterial and fungal infections, Evans said, because workers kill the infection before it produces spores that can infect the rest of the colony.

Honeybee colonies also employ this tactic against parasites such as Varroa destructor, a mite that attaches to the bee's body and feeds on its fat. Varroa infections can cripple a bee colony, but behaviors such as hygienic cannibalism largely keep the mites in check.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But it turns out, DWV uses the bees' own defenses against them. Varroa mites are just the Trojan horses that allow the virus access to the whole colony.

"This virus has been around for a long time, but it has only become a problem in recent years as it has made this connection with the mites," Evans said. Varroa mites, while a threat on their own, have become more dangerous since the 1980s as DWV has evolved to use them as a vector.

To learn more about the virus' mode of transmission, Evans and his colleagues purposefully infected honey bee pupae in a laboratory colony with Varroa mites. These mites were carrying a specific strain of DWV that contained an identifiable genetic barcode. After infecting pupae, workers would come along, uncap the infected pupae, and eat most of the pupae. The researchers then tested the workers for the presence of the experimental strain of DWV and found that while cannibalism easily controlled the mites, the workers were often infected with DWV. Their second experiment explored how the virus spreads among the workers. It turned out, the virus was short-circuiting yet another beneficial behavior in the bees, called trophallaxis, in which worker bees that have had a meal often share that food with their hungrier sisters by regurgitating a portion into their mouths.

—Photos: murder hornets will haunt your nightmares

—7 amazing bug ninja skills

—See 15 crazy animal eyes: Rectangular pupils to wild colors

To examine transmission via trophallaxis, the researchers divided worker bees into groups and separated those groups by wire mesh. The mesh prevented the groups from mixing, but still allowed for the exchange of food from one side to the other. After bees on one side cannibalized DWV-infected pupae, they passed food through the mesh to the other group. The researchers found significantly higher levels of DWV transmission to the bees that received regurgitated food.

"There's a paper from the 50s where the researchers gave bees food with radioactive tracers in it, and they found that each bee has an immediate network of nearly 2,000 other bees," Evans said.

Until the 1980s, DWV was considered a latent virus that only the queen would pass to the occasional offspring. Now, DWV spreads like wildfire through honeybee colonies by hijacking their own hygienic behaviors.

But the bees are caught in a bind, because bees without these hygienic behaviors really don't last long once the mites have infected the colony.

"This combo of mites and viruses is really the biggest challenge for beekeeping right now," Evans said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.