'Complete lack of sunlight' killed a Renaissance-era toddler, CT scan reveals

CT scans of the child's mummy show that the toddler, a descendant of an Austrian count, died from a vitamin D deficiency due to lack of sunlight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A "virtual autopsy" of the mummified remains of a toddler buried inside a family crypt in Austria reveals that the child died from a lack of sunlight, a new study finds.

Believed to be Reichard Wilhelm, the first-born son of a Count of Starhemberg, a prominent member of the Austrian aristocracy, the young boy lived during the Renaissance (between the 14th and 17th centuries) and died when he was just 10 to 18 months old. Yet despite his privileged upbringing, a team of scientists from Germany concluded that he experienced "extreme nutritional deficiency and a tragically early death from pneumonia," according to a statement.

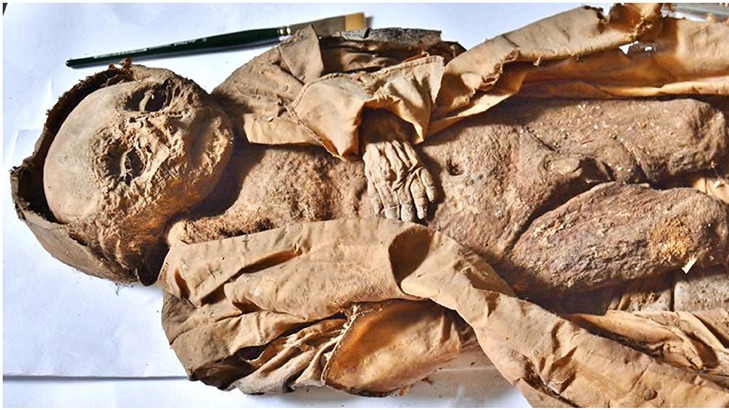

Scientists made the discovery while performing a CT scan and radiocarbon dating of the mummy, which was found wrapped in a hooded silk coat, his left hand draped across his abdomen. The scans showed malformations on his ribs, classic signs of malnutrition, which "points to rickets," according to the study, published on Oct. 26 in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

Related: 7 famous mummies and secret's they've revealed about the ancient world

Known as a rachitic rosary, those malformations occur when knobs of rib bone begin to resemble rosary beads due to a vitamin D deficiency. The boy's remaining soft tissues showed that he was also overweight when he died, eliminating the possibility that he was underfed.

"The combination of obesity along with a severe vitamin deficiency can only be explained by a generally 'good' nutritional status along with an almost complete lack of sunlight exposure," Andreas Nerlich, the study's lead author and a pathologist from the Academic Clinic Munich-Bogenhausen in Germany, said in the statement. "We have to reconsider the living conditions of high aristocratic infants of previous populations."

Researchers found the child buried inside a wooden coffin that proved to be too small for him, based on a deformation of his skull. The crypt was reserved exclusively for descendants of the Counts of Starhemberg, specifically their first-born sons who would have been titleholders, as well as the men's wives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Radiocarbon dating of a skin sample suggested he was buried between 1550 and 1635, however building records indicate that the crypt underwent a renovation around 1600, so he likely was buried after that date. He was the youngest person buried in the crypt, according to the statement.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus