World's oldest mummy found in Portugal

Previously undeveloped photos reveal 8,000-year-old signs of mummification — the earliest evidence found anywhere in the world.

Roughly 60 years ago, an archaeologist snapped photos of several skeletons buried in 8,000-year-old graves in southern Portugal. Now, a new analysis of these previously undeveloped photos suggests that the oldest human mummies don't hail from Egypt or even Chile, but rather Europe.

More than a dozen ancient bodies were found in Portugal's southern Sado Valley during excavations in the 1960s, and at least one of those bodies had been mummified, possibly to make it easier to transport before its burial, researchers said after analyzing the images and visiting the burial grounds.

And there are signs that other bodies buried at the site may have also been mummified, which suggests that the practice could have been widespread in this region at this time.

Elaborate procedures of mummification were used in ancient Egypt more than 4,500 years ago, and evidence of mummification has been found elsewhere in Europe, dating from about 1000 B.C. But the newly identified mummy in Portugal is the oldest ever found and predates the previous record holders — mummies in the coastal region of Chile's Atacama Desert — by about 1,000 years.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

Although mummification is relatively straightforward in very dry conditions like the Atacama Desert, it is difficult to find evidence for it in Europe, where much wetter conditions mean that mummified soft tissues rarely stay preserved, said Rita Peyroteo-Stjerna, a bioarchaeologist at Uppsala University in Sweden.

"It's very hard to make these observations, but it's possible with combined methods and experimental work," she told Live Science. Peyroteo-Stjerna is the lead author of a study on the discovery published this month in the European Journal of Archaeology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Undeveloped photographs

The evidence of mummification comes from several rolls of photographic film found among the belongings of a deceased Portuguese archaeologist, Manuel Farinha dos Santos, who died in 2001.

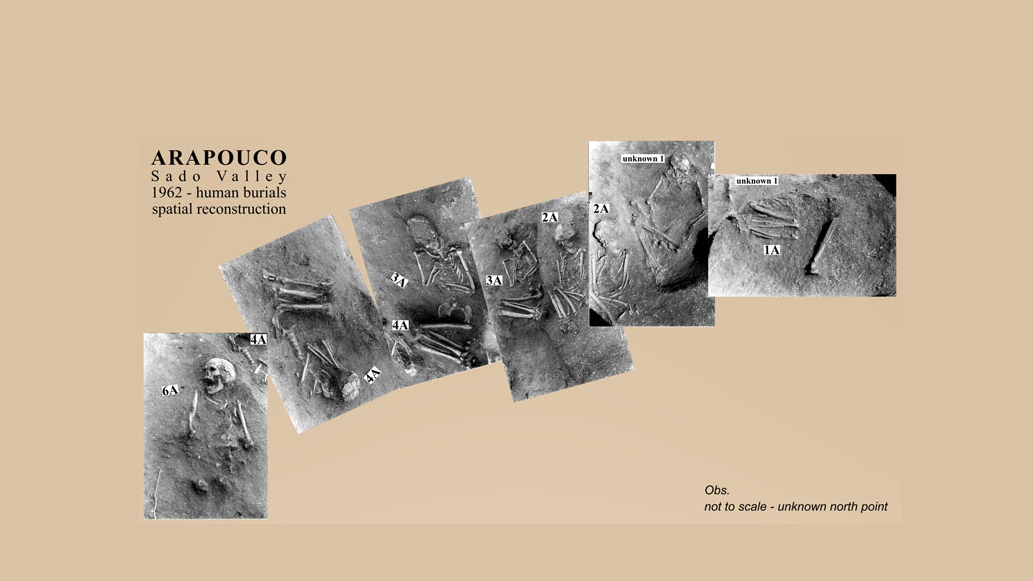

Farinha dos Santos had worked on human remains excavated from the Sado Valley in the early 1960s. When the researchers on the new study developed the images, they discovered black-and-white photographs of 13 burials from the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age.

Although some documentation and hand-drawn maps of the site were held in the National Museum of Archaeology in Lisbon, these photographs were previously unknown and gave archaeologists a unique opportunity to study the burials, Peyroteo-Stjerna said.

After using the photographs to reconstruct the burials at the two sites, the scientists observed that the bones of one skeleton were "hyperflexed" — that is, the arms and legs had been moved beyond their natural limits — which indicated the body had been tied with now-disintegrated bindings that were tightened after the individual's death.

In addition, they noted the bones of the skeleton were still articulated, or attached and in place, after the burial — in particular the very small bones of the feet, which usually fall apart completely when a body decomposes, she said.

There were also no signs that the soil of the ancient grave had moved as the soft tissue of the body decomposed — a process that shrinks the volume of the body, resulting in the surrounding sediment filling in the voids left behind — suggesting there was no such decomposition.

Related: 24 amazing archaeological discoveries

Taken together, these signs indicated that the body had been mummified after death; the individual was likely deliberately desiccated and then progressively made smaller by the tightening of the bindings, she said.

Forensic mummification

The assessment of the ancient burials also relied on findings from human decomposition experiments conducted at the Forensic Anthropology Research Facility at Texas State University, where one of the researchers had studied, Peyroteo-Stjerna said.

Those experiments on recent cadavers showed which steps ancient people likely took while mummifying the individual in the Sado Valley, she said.

It seemed the dead person had been trussed up and probably placed on an elevated structure, such as a raised platform, to allow decomposition fluids to drain away from further contact with the body, the researchers wrote in the study.

It also seemed the mummification procedure included the use of fire to dry out the cadaver, and that the bindings on the body were progressively tightened over time, retaining its anatomical integrity while increasing the flexion of the limbs, the researchers wrote.

While evidence from other ancient skeletons from the same site had suggested those bodies were treated in the same way, those specimens do not show the same combination of evidence, Peyroteo-Stjerna said.

If some of the dead were brought to the Sado Valley sites from elsewhere to be buried, as the researchers suggest, then mummification — which resulted in much smaller and lighter dead bodies — would have made them easier to transport, she said.

Archaeologist Michael Parker Pearson of University College London, who wasn't part of the Sado Valley research, said his team had developed these techniques to identify mummification in prehistoric skeletons almost 20 years ago: "So it is very exciting to see the practice recognized elsewhere in Europe," he said.

Parker Pearson's team had found evidence for mummification in skeletons from an island in Scotland that were about 3,000 years old; and while the mummified skeleton from the Sado Valley was much older, it might not stay the oldest-known for long, he told Live Science in an email.

Suggestions of 10,000-year-old mummifications had been found at El Wad and Ain Mallaha in Israel, and there were signs of mummifications 30,000 years ago at Kosteni in Belarus. "These sites are just crying out for the type of analysis carried out in this new study," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus