UV radiation pulse played a role in a mass extinction event, fossilized pollen reveals

250 million-year-old pollen suggests radiation played a role in mass extinction event

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A lethal pulse of ultraviolet (UV) radiation may have played a role in Earth's biggest mass extinction event, fossilized pollen grains reveal.

Pollen that dates to the time of the Permian-Triassic mass extinction event, roughly 250 million years ago, produced "sunscreen" compounds that shielded against harmful UV-B radiation, the analysis found. At that time, approximately 80% of all marine and terrestrial species died off.

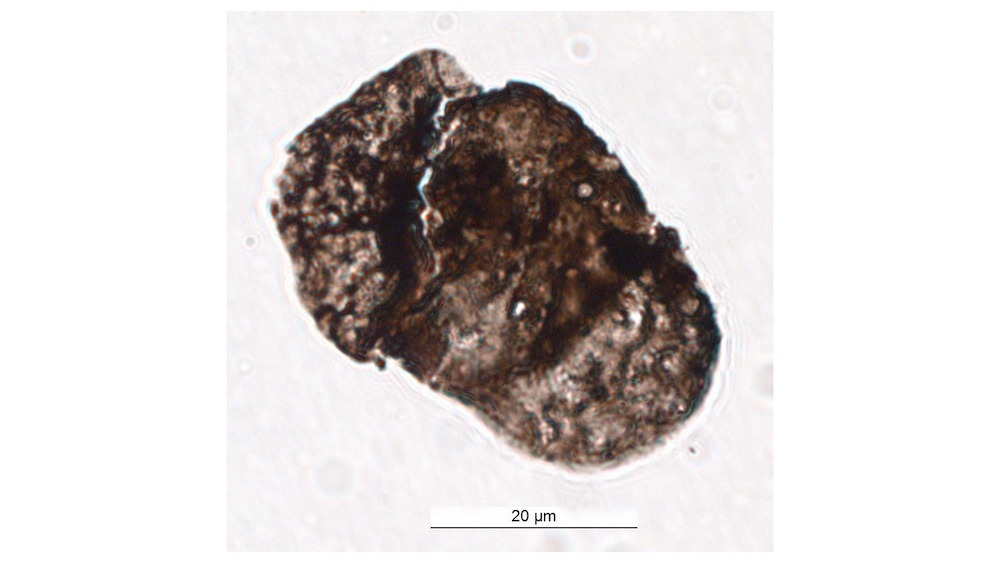

For the study, which was published Jan. 6 in the journal Science Advances, a team of international scientists developed a new method of using a laser beam to examine the miniscule grains, which measure about half the width of a human hair and were found embedded onto rocks unearthed in southern Tibet, according to a statement.

Plants rely on photosynthesis to convert sunlight into energy, but they also need a mechanism to block out harmful UV-B radiation.

"As UV-B is bad for us, it's equally as bad for plants," Barry Lomax, the study's co-author and a professor in plant paleobiology at the University of Nottingham in the U.K., told Live Science. "Instead of going to [the pharmacy], plants can alter their chemistry and make their own equivalent version of sunscreen compounds. Their chemical structure acts to dissipate the high-energy wavelengths of UV-B light and stops it from getting within the preserved tissues of the pollen grains."

Related: 3.5 billion-year-old rock structures are one of the oldest signs of life on Earth

In this case, the radiation spike didn't "kill the plants outright, but rather it slowed them down by lessening their ability to photosynthesize, which caused them to become sterile over time," Lomax said. "You then wind up with extinction driven by a lack of sexual reproduction rather than the UV-B frying the plants instantly."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Experts have long theorized that the Permian-Triassic extinction, classified as one of the five major extinction events on Earth, was in response to a "paleoclimate emergency" caused by the Siberian Traps eruption, a large volcanic event in what is now modern-day Siberia. The catastrophic incident forced plumes of carbon buried deep within the Earth's interior up into the stratosphere, resulting in a global warming event that "led to a collapse in the Earth's ozone layer," according to the researchers.

"And when you thin out the ozone layer, that's when you end up with more UV-Bs," Lomax said.

In their research, the scientists also discovered a link between the burst of UV-B radiation and how it changed the chemistry of plants' tissues, which led to "a loss of insect diversity," Lomax said.

"In this case, plant tissues became less palatable to herbivores and less digestible," Lomax said.

Because plant leaves had less nitrogen, they were not nutritious enough for the insects that ate them. That may explain why insect populations plummeted during this extinction event.

"Often insects come out unscathed during mass extinction events, but that wasn't the case here," Lomax said.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus