Copy of famous Teotihuacan structure discovered in Maya city

Who built a copy of a famous Teotihuacan Citadel in Tikal?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A pyramid and courtyard unearthed in the Maya city of Tikal may have once been an embassy of sorts for visitors or ambassadors from the megapolis of Teotihuacan, more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) away.

The apparently peaceful outpost may have represented a period of cooperation between Tikal, in what is today Guatemala, and Teotihucan, which is near modern-day Mexico City. A century or so after the structure was built, invaders — quite possibly from Teotihuacan — would take over Tikal.

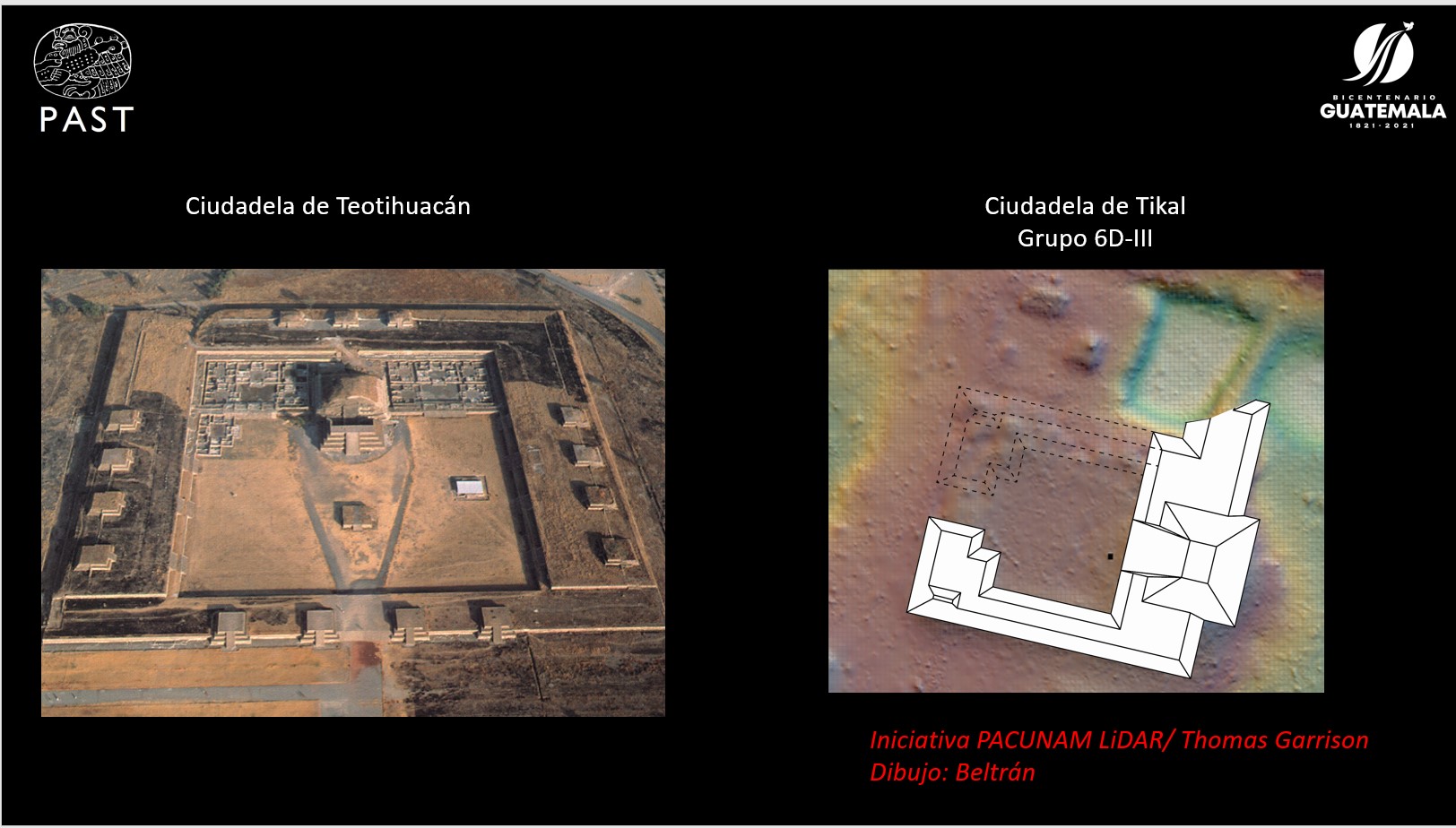

The enclosed courtyard and stair-step pyramid look like a miniature version of a structure called La Ciudadela, or The Citadel, in Teotihuacan. That citadel contained a temple known as the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent and a 38-acre (15.2 hectare) courtyard large enough to accommodate 100,000 people. The smaller version in the Maya city of Tikal not only has the same layout, but it also has the same orientation and is full of artifacts with links to Teotihuacan, including a Teotihuacan-style grave.

Related: Photos: The amazing pyramids of Teotihuacan

"That means there is a really long occupation of people associated with Teotihuacan" in Tikal, said excavation leader Edwin Román Ramírez, an archaeologist at the Foundation for Maya Cultural and Natural Heritage (PACUNAM) who announced the finding in a press conference April 8.

Ancient connections

Tikal was a Maya city that may have been home to tens of thousands of people during its peak during the Maya Classic Period between about A.D. 250 to A.D. 900. After a series of homegrown rulers, the city was conquered in A.D. 378 by a general named Siyah K'ak. In stone carvings, the general is depicted as serving a leader represented by a spear-thrower and an owl, a carving also found in Teotihuacan. The connection had led many archaeologists to believe that the foreign conquerors came from Teotihuacan.

But the two cities' relationship probably didn't start there. More than 100,000 people may have lived at Teotihuacan during its peak in the first half of the first century A.D., and its cultural influence seems to have had far reach. Teotihuacan-style art and artifacts have long been found in excavations in Guatemala, Román Ramírez told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: In photos: Hidden Maya civilization

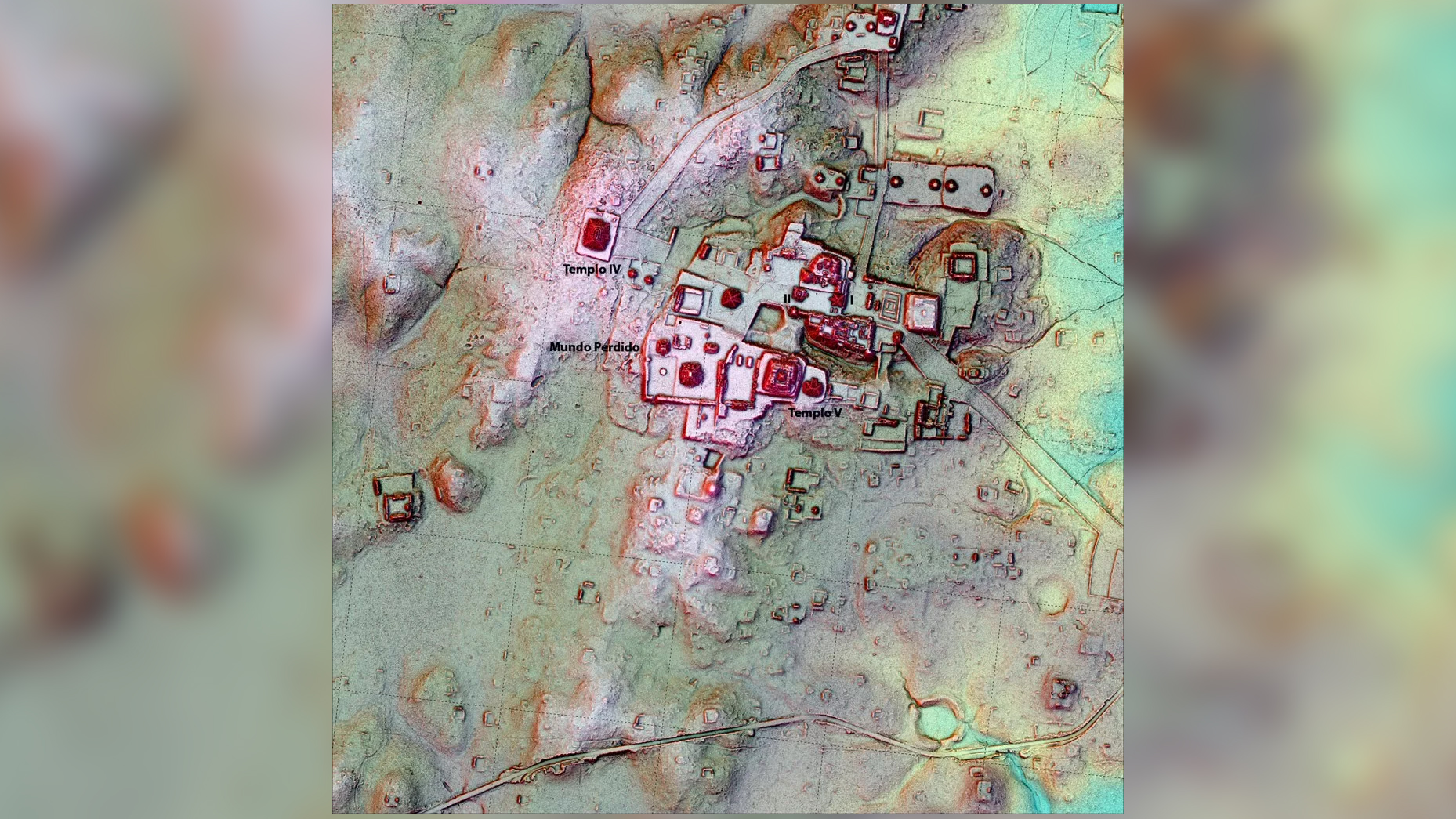

Román Ramírez and his team first spotted the new pyramid and courtyard structure on a lidar survey in 2019. Lidar (or light detection and ranging) uses laser beams shot from an airplane to accurately map the topography below. Tikal is in a rainforest, so mounds containing old ruins are easy to miss; lidar virtually clears away the vegetation to highlight any shapes that need further investigation.

Four months of excavation revealed a structure built in six different stages. Researchers don't know much about the first stage of construction yet, but the second stage dated to about A.D. 250 and was reminiscent of architecture found in Central Mexico. The third stage, built soon after, began to resemble The Citadel of Teotihuacan. The pyramid and courtyard were even oriented 13 degrees east of true north, very similar to ceremonial structures in Teotihuacan, which were situated 15 degrees east of true north.

Within this stage, researchers found a grave. They don't yet know much about the person whose remains were interred inside, but the deceased had been covered with a thin layer of broken ceramics and surrounded by green obsidian dart points that were used by Teotihuacan warriors. Only six similar burials have been found in Tikal, Román Ramírez said, and chemical analysis of one of the skeletons in those burials revealed that the person grew up in Central Mexico.

Intriguingly, the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent in Teotihuacan's Citadel is home to a mass grave of more than 200 people, probably captives, who were also buried with dart points and ceramic shards.

"We don't know if the burial that we found is a local person or is someone else, or if he was a captive," Román Ramírez said, but the researchers are in the process of studying the bones.

Cultural exchange

The later construction phases also showed evidence of mysterious rituals, including thousands of pieces of ceramics, incense holders used in Teotihuacan ceremonies and art representing the rain deity of Teotihuacan. The incense holders appear to be made from a mix of local and foreign materials, suggesting that someone familiar with Teotihuacan artistry was manufacturing them in Tikal, Román Ramírez said.

The researchers have found a few other hints around Tikal that Teotihuacans or people who had adopted Teotihuacan culture were living in the Maya city. For example, there is a residential compound the city constructed with soil covered by stucco, a Teotihuacan style of architecture. The same architecture is seen at the miniature Citadel in Tikal.

The researchers plan to spend four more months excavating the Tikal citadel this year, and will extend the excavations into 2022 if there is more to find. The research is revealing how much connection there was between Central America cities in this period, Román Ramírez said.

"What is interesting and important for us is to show how Tikal was a very multicultural city," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus