Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The search for life in the universe tends to focus on habitable environments. But to answer questions about how life emerged and spread, as well as the limits of habitability, researchers may want to consider looking at dead worlds — and perhaps even (very carefully) seeding them with life.

"The biological study of lifelessness seems counterintuitive, because biology is the study of life," said astrobiologist Charles Cockell of the University of Edinburgh in the U.K.

But in a paper set to be published in April in the journal Astrobiology, Cockell makes the case that focusing entirely on living worlds leaves out an enormous and potentially informative percentage of the cosmos. The mind-bogglingly large spaces between planets, as well as places like the burning sun and frigid moon, are all presumably devoid of life.

Related: 9 strange, scientific reasons for why humans haven't found aliens yet

Even Earth, which we consider to be teeming with life, is largely uninhabitable, with a thin biosphere situated on the surface but a largely dead interior, Cockell told Live Science.

Surveying lifeless worlds could help scientists learn exactly what percentage of the universe is uninhabitable, what proportion is potentially habitable but just lacking in life, and whether there are some worlds that are partially empty and partially covered in life.

After organisms emerged during the dawn of our planet, they are thought to have proliferated to fill every habitable environment they could find. Yet the details of this process are still only hazily understood, and Cockell thinks dead worlds could help provide scientific insight into fundamental questions such as the limits of where life can exist and how living things colonize uninhabited areas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dead worlds could also provide a clean slate, where scientists could start the experiment of life from scratch. If researchers were to release small quantities of microbes into lifeless environments, they could learn how quickly organisms spread, the sequence in which different species take over, and how living things alter the local chemistry and eventually start to co-evolve with a planet, he added. Future astronauts in a base on Mars might discover the best bacteria to introduce into its surface in order to make it productive for crops.

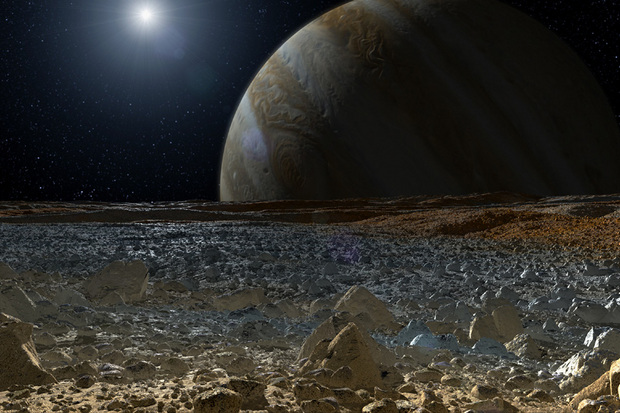

Determining the right place to conduct such an experiment might prove tricky. It is not entirely clear which places in the solar system are totally dead. Many astrobiologists think the ice-covered oceans of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are good bets to find life, but Cockell pointed out that some environments can be habitable yet are still uninhabited.

So, if the watery depths of Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus were to prove lifeless, perhaps it could be informative to unleash bacteria into them and monitor them over an enormous timespan, such as 10,000 years. "It would be like the Star Trek Genesis experiment," he said, referring to a fictional device capable of generating an entire biosphere on a dead body.

Cockell acknowledged that such ideas carry significant ethical concerns, including whether we have the right to alter planets beyond ours for our own purposes. Other places in the solar system are legally protected from contamination under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty—written largely by the United States and Russia and signed by every spacefaring nation in the world—and Cockell thinks it would be important to make sure that a world or environment is actually lifeless before rushing in and potentially changing it forever.

In 2019, the Israeli lunar lander Beresheet crashed into the surface of the moon carrying a secret bounty of tardigrades — hardy organisms capable of surviving in extreme conditions, Live Science previously reported. Though Cockell thinks the creatures are probably dead, their arbitrary introduction didn't sit well with him.

One final reason to study lifeless environments might be to accidentally stumble across life, Cockell said. Few thought that volcanic hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean could be habitable until submarine exploration showed them to be bursting with organisms. Such places helped redefine our understanding of where living things can survive and show us life as we don't know it, he added.

"The main point is to not get too obsessed with looking for life and habitable environments," Cockell said. "Lifeless worlds can tell us a lot."

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus