Cathedral's stained-glass windows 'witnessed' medieval murder of Archbishop of Canterbury

Four of the panels date as far back as 40 years before Thomas Becket's grisly death.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The stained-glass windows of England's Canterbury Cathedral are so old that they "witnessed" one of medieval England's most infamous murders, a new study reveals.

The analysis shows that some of the cathedral's stained-glass windows, which depict prophets that preceded Jesus, could date as far back as the mid-1100s, making them the oldest in Britain and among the oldest in the world.

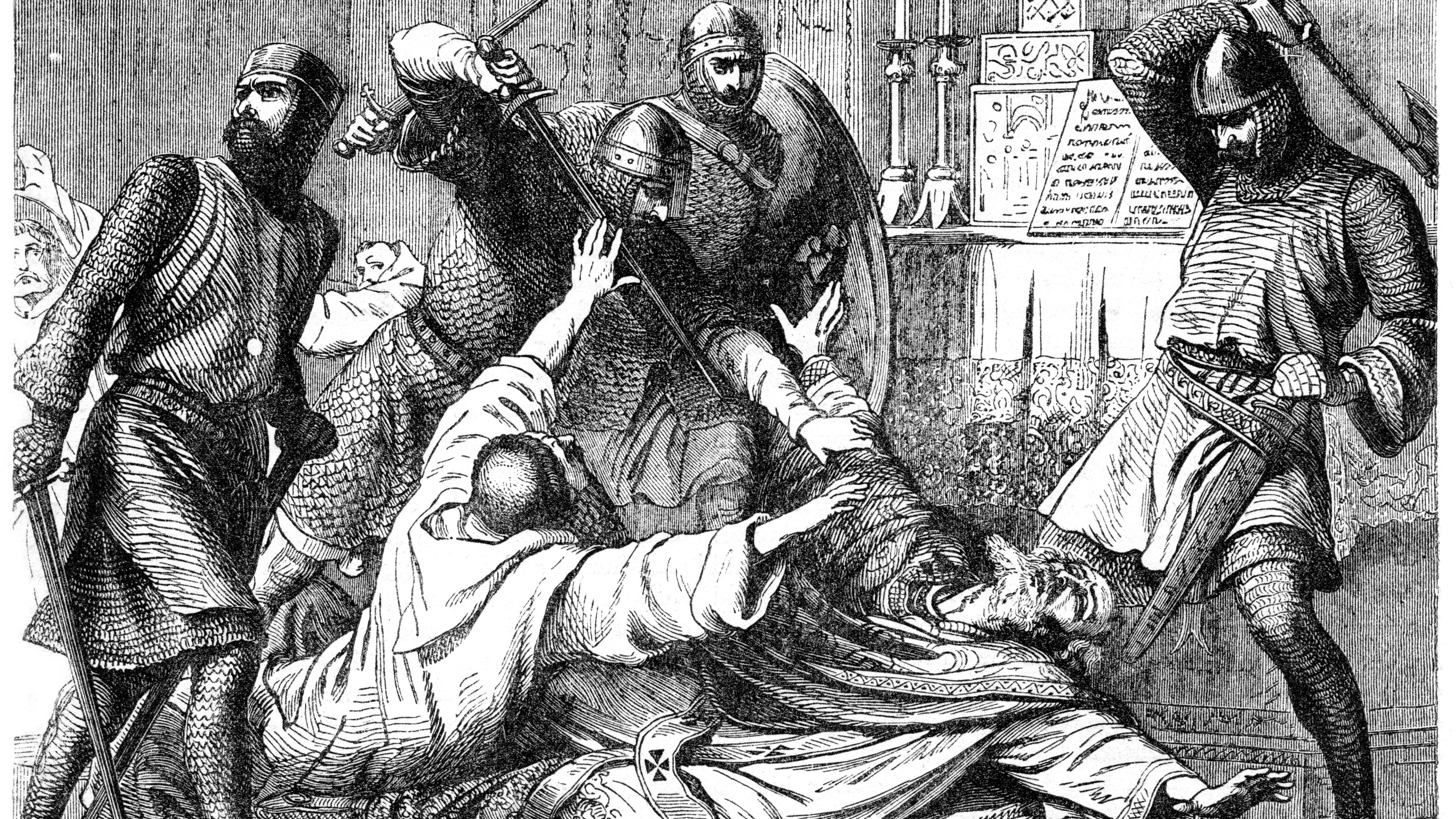

This means that some of the windows may have overlooked the murder scene of Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury who was slain at the cathedral's altar by soldiers loyal to Henry II in 1170.

Related: 12 bizarre medieval trends

Léonie Seliger, head of stained-glass conservation at the cathedral, told BBC News that she was so happy to hear the news, she was "ready to dance." She said the windows "would have witnessed the murder of Thomas Becket, they would have witnessed Henry II come on his knees begging for forgiveness, they would have witnessed the conflagration of the fire that devoured the cathedral in 1174. And then they would have witnessed all of British history."

Born to a rising mercantile family, Becket plied powerful social connections to enter the household of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury and to gain the confidence of King Henry II, who first appointed Becket as his royal chancellor and later as his new archbishop after Theobald's death. As Becket discovered his newfound authority — derived not from the crown but from God and the Catholic Church — he and Henry, once close friends, became bitter rivals and struggled to assert their supremacy over each other. Henry took Becket's land and money from him; Becket, in turn, excommunicated many of Henry's closest allies.

Tensions finally boiled over during the winter of 1170. Becket had been exiled to France, and his return to England drew ire from the king, who launched into a furious invective concerning his former friend. "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" the king is rumored to have said aloud at Christmas in his castle in Bures, Normandy. Four knights in the king's retinue who caught news of his displeasure traveled to Canterbury Cathedral to confront Becket.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After the priest refused to be placed under arrest, the knights returned with swords. A brief scuffle ensued, and Becket insulted one of the knights, causing the man to draw his weapon. By the altar and under the light streaming through the windows, four sword blows rained down on the priest's head, slicing open his skull, scattering his brains over the cathedral floor, and shattering the tip of the sword which delivered the final strike, according to the account of Edward Grim, a monk who had watched the attack from a hiding place. Villagers came to collect the dead priest's blood, even rubbing it over their faces and clothes. Becket, by then transformed into a powerful martyr who would later be canonized, haunted the conscience of the king for the remainder of his life.

A fire devastated the cathedral four years later. Until now, historians thought none of the original glass panels that had witnessed the gory scene had survived.

Researchers didn't intend to prove that the glass panes dated back to these troubled times. Rather, they were trying to analyze them without taking physical samples. The method, called portable X-ray fluorescence, fired X-rays at the stained glass, which absorbed electrons. The electrons then radiated that energy back out in different wavelengths. These different wavelengths revealed the chemical fingerprint of the glass. By looking at how the chemical components have changed over time, the researchers were able to figure out the age of the glass.

The team focused on four windows known as the Ancestors of Christ, in part because Madeleine Caviness, an art historian at Tufts University in Massachusetts, had proposed in 1987 that these panels were stylistically older than others in the church. The team's three-year-long analysis showed that the windows were made between 1130 and 1160, half a century earlier than had been previously assumed.

Lead study author Laura Ware Adlington, an independent materials scientist who developed the new analysis method, said in a statement that the agreement between Caviness' analysis and the new fluorescence dating were "rather remarkable," even down to details such as the prophet Nathan's hat "which [Caviness] identified as an early-13th-century addition, and the scientific data confirmed was made with the later glass type found at Canterbury."

Caviness, now 83, told BBC News that she was ''delighted'' to hear that her analysis had been confirmed after nearly 35 years and that the news had jolted her from a "COVID numbness" that she had been feeling.

"The scientific findings, the observations and the chronology of the cathedral itself all fit together very nicely now,'' Caviness said. "I wish I was younger and could throw myself more into helping Laura with her future work. But I've certainly got a few more projects to feed her.''

The researchers published their findings June 5 in the journal Heritage.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus